“There is no end to education. It is not that you read a book, pass an examination, and finish with education. The whole of life, from the moment you are born to the moment you die, is a process of learning.” — Jiddu Krishnamurti

I believe the goals of learning and teaching are the same–to find and share a passion for seeking truth, to promote creative and critical thinking, and to cultivate empathy and tolerance. You can teach facts, advance knowledge, help educate, and even test and grade what is learned in the process; but value, wisdom, and experience cannot be taught. They are realized, embraced, and always open to growth and change. They live in the hearts of both students and teachers who see education as a daily and lifetime affair. As W.B. Yeats proclaims, “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.”

My Life as a Student

“Your entire education has deprived you of the capacity for living in the moment because it was preparing you for the future, instead of showing you how to be alive now.” — Alan Watts

Admittedly, it took me years to find a passion for learning in school. I had some good teachers and rather enjoyed history, science, and literature, but my K through 12 years were spent as a means to an end–to play professional basketball. Playing hoops was my passion. Scholastically, I did what I had to, which wasn’t much, particularly in my senior year. I did manage a 3.3 GPA but didn’t deserve it. I didn’t even take my final exams because I spent the week practicing with an all-star team getting ready for the Roundball Classic in Detroit. I missed over 15 percent of my classes because of college recruiting trips and went to school at noon on days of home games. A month before graduation, it was brought to the principal’s attention that I didn’t have enough credits to graduate. I recall meeting with the superintendent, the principal, and the head of academic counseling to “figure something out.” They decided to give me credits under the rubric of the co-op program for helping out with basketball clinics run by the Cadillac All-Sports Association. I realize this rings of the privileged patriarchal program that dominates our culture, but at the time I was grateful for all the support I received for my full-blown pursuit of a basketball career.

I might not have been the best high school student, but I did have tangential academic interests that none of my teachers talked about. For instance, I introduced myself to Freud. I’d heard he’d explained away the need for religion, discovered the inroads to the unconscious mind, and considered sex, food, and power as the forces that drive human behavior. So I read his Future of an Illusion and snippets of his work from anthologies and biographies and was afraid he made a lot of sense. The idea that much of religion is built on people’s fear of death because of attachment to the ego actually depressed me. I remember confronting our minister, Bill Allinder, in his office one Sunday shortly after service. I had to know, what if Freud is right? I’ll never forget the care and wisdom that Dr. A (that’s our nickname for him) shared with me that afternoon. He explained that Freud was an effective psychoanalyst, but dealt with only very specific aspects of the human psyche. Freud focused on the personal unconscious, trying to fix it through technical means much like a doctor would try to fix a broken arm. More importantly, Freud considered humans to be products of a purposeless, uncaring cosmos and that we all suffer from a split self, that the ego is the battleground between the super-ego (“the internalized voices of authority”) and the instinctual, pleasure-oriented id. The ego’s job is to sublimate the id and activate the reality principle, which presumes an ego-sustained separation from nature that Freud insisted was necessary because nature “destroys us—coldly, cruelly, relentlessly.” With help from Dr. A, I discovered there were more things in heaven and earth than Freud ever dreamt of in his psychology.

My collegiate education started out much like high school. I didn’t even register for classes my first semester at Central Michigan University, the team’s advisors did. I had to take the comp. 1 and library courses, but when I told them I liked religion, philosophy, and art, I got an intro course in each. I got all B’s and remember thinking this was as easy as high school with even easier classes, including Bowling, Badminton, Personal Health, and Coaching Basketball–which were all taught by coaches. The summer after my second knee surgery, when I dropped out for a semester and they had to get me enough credits to be eligible for the fall, I took a Phys. ed. course called Workshop Leisure Time—which was taught by a coach and consisted of some afternoon bike rides—and two recreation courses called Field Course Rec. and Camping (the first two classes were three-credit courses, but somehow the third was five credits). Admittedly, I never went to or met the teacher of either class. I got A’s in all three courses.

My Religion of India course was the first one I remember actually experiencing the joy of learning. It helped that I was fascinated with Hinduism and Buddhism, the Bhagavad Gita and Dhammapada, and concepts such as ahimsa and pantheism. The class also made me realize I actually love learning, but not under the auspices of grades or compulsion. As Winston Churchill put it, “I am always ready to learn although I do not always like being taught.” I also enjoyed my Ethics class. The teacher, John Gill was an old hippie (with long hair but bald on top) and world traveler who had just come back from sailing around Iceland in time to teach the class. He was so enthusiastic and his eyes would light up when we’d get into discussions. We always sat in a circle and only read one book all semester, Spinoza’s Ethics. I’ve been a Spinoza disciple ever since I was 12 or 13, when, after church one summer Sunday, my brother Gary–one of my first teachers/mentors–and I had a discussion about Spinoza in our backyard. I had just read his paper on pantheism that Mom typed for one of his courses, and he cited Spinoza often. I’ve always been a pantheist but didn’t know it until that discussion. In Spinoza’s words, “Whatever is, is in God, and nothing can be or be conceived without God.”

The highest activity a human being can attain is learning for understanding because to understand is to be free.

The endeavor to understand is the first and only basis of virtue.

If you want the present to be different from the past, study the past.

I do not know how to teach philosophy without becoming a disturber of the peace. — Spinoza

I had a brilliant professor, Nolan Kaiser, for Presocratic Philosophy my sophomore year, another class I truly enjoyed and never missed. The first paper I considered noteworthy–which was on Pythagoras, Heraclitus, and the Presocratic Notion of Mind in Nature–was for his class. I also remember the one I wrote on Ralph Waldo Emerson and the balance of nature’s polarities for my American Philosophy class. Along with Spinoza, Emerson became an instant academic hero and helped initiate my awareness of the three paradigms, which became the foci of much of my own writings. He drew his Earth wisdom (my name for the first paradigm) from Mother Goddess traditions, Eastern philosophy, and Dionysianism (under the names of Bacchus, Pan, and Orpheus). Emerson’s notion of a “balanced soul”–which he considered the goal of being human–is ordained by nature: “Each thing is a half, and suggests another thing to make it whole; as, spirit, matter; man, woman; odd, even; subjective, objective; in, out; upper, under; motion, rest; yea, nay… Whilst the world is thus dual, so is every one of its parts. The entire system of things gets represented in every particle.” Much like Emerson, I believe we forfeited the balance inherent to that holistic system for an imbalanced, male-dominant worldview.

Emerson warned that Christian and scientific dogma, the core of the second or reason-as-virtue paradigm, sanctified the masculine “ego” and harbored an unbalanced way of thinking and being. By portraying Jesus as a “demigod,” an “Apollo,” Christian church fathers and “the following ages” emphasized the “biographical ego” as opposed to glorifying the “universal ego”; hence, the tradition has suppressed the mystical Kingdom within by exaggerating the person and not the message of Jesus. As such, it “corrupts all attempts to communicate religion” and, in the process, helped create a “Monster” that “is not one with the blowing clover and falling rain.” The failure of science rests in its inability to recognize “the relation of the parts to the whole.” Sacrificing truth and unity of being for classification of objects and “minuteness in details,” science lacks the “metaphysics” to convey the purpose and direction needed for a complete view; hence, it “overlooks that wonderful congruity which subsists between man and the world.” Under science’s spell, man’s “relation to nature” can be summarized as “his power over it.”

Emerson’s version of the third paradigm, ecocentrism, was so insightful that I’m not sure, despite the fact you can get his works in most bookstores, that he is truly appreciated for the breadth of his vision. His notion of the “balanced soul” identifies the self with nature’s evolving mindfulness. As he pleaded in “The Over-soul,” “Let us learn the revelation of all nature and thought; that the Highest dwells within us, that the sources of nature are in our own minds.” A son and grandson of preachers, Emerson endorsed a Jesus who preached ecumenism and shared a non-apocalyptic, pantheistic message. He believed we should recover Jesus’ true message, that “god incarnates himself in man, and evermore goes forth anew to take possession of his World”; that we should realize that the false separation of the “holy” spirit from “evil” matter distorted Jesus’ portrayal of the kingdom as ever-present, as available to anyone willing to see into “the mystery of the soul” and, as Jesus did, “to expand to the full circle of the universe,” practice “spontaneous love,” and cultivate a psyche in harmony with nature. In his words, “The ancient precept, ‘Know Thyself,’ and the modern precept, ‘Study nature,’ become at last one maxim.”

The secret in education lies in respecting the student.

A great teacher makes hard things easy.

Teaching is the perpetual end and office of all things. Teaching, instruction is the main design that shines through the sky and earth.

The things taught in schools and colleges are not an education, but the means to an education.– Ralph Waldo Emerson

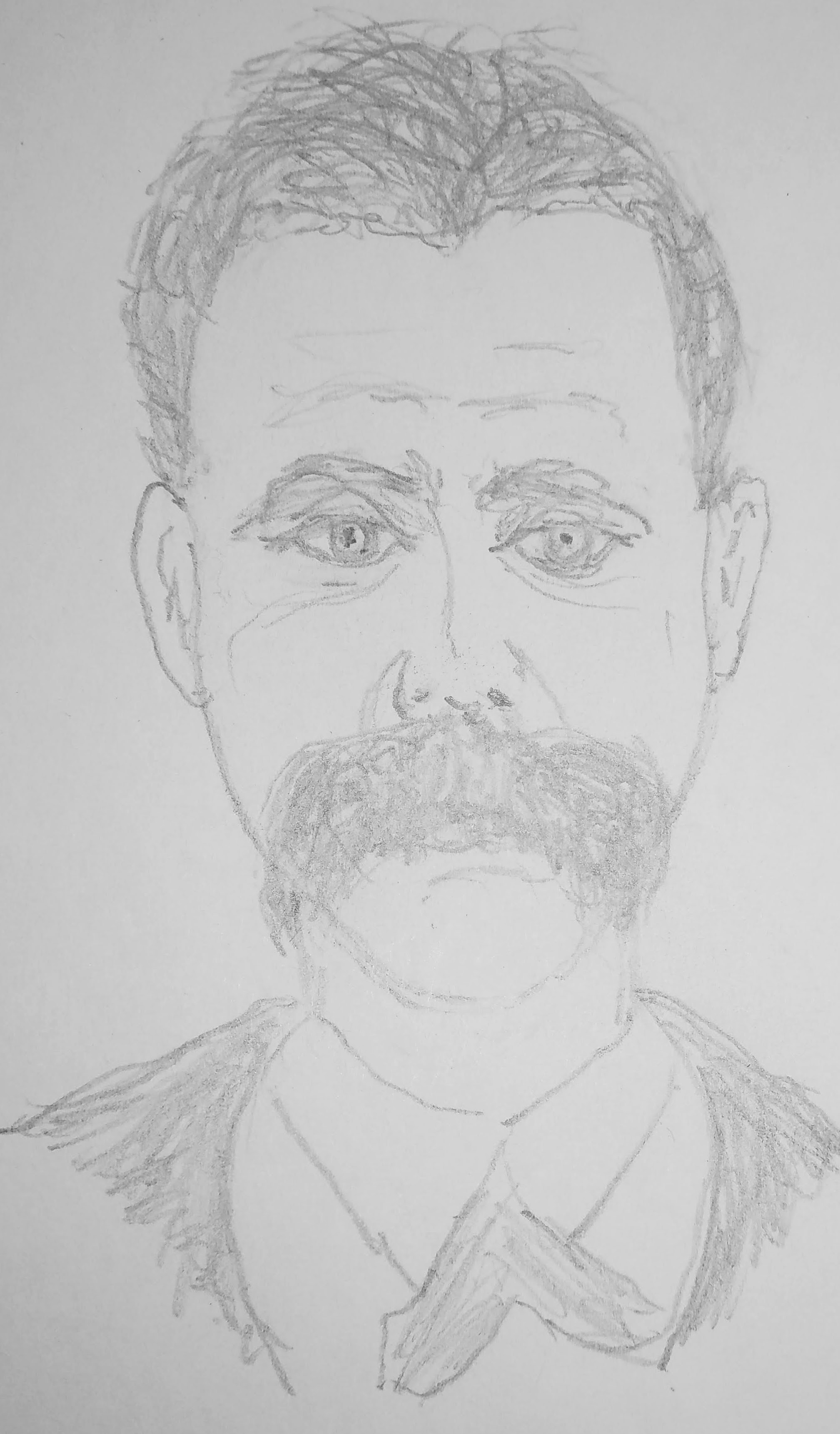

I also took three psychology courses which I liked so much that I became a teaching assistant. I would have probably stuck with it, but after yet another operation, I decided to transfer to Eckerd College to focus on my studies. During my first semester, I took Analytic Philosophy, History of Modern Philosophy, Understanding the Bible, and two other courses. I lived off-campus in a tiny but quaint apartment that had everything I needed—a typewriter, bookcase, huge desk, swivel chair, and NO television. With my leg in another cast, on some weekends I would lock my door late Friday afternoon and literally unlock it on my way to class Monday morning. I read voraciously–not only what I needed for classes but also books that sparked my interest, including many of Friedrich Nietzsche’s. I went to Haslam’s bookstore and bought about a dozen used books by or about him (years later, my friend German, bought me Nietzsche’s Sämtliche Werke or Collected Works that included previously unpublished manuscripts, in German). The Birth of Tragedy was published when Nietzsche was 28 and it raised a stir. He described how ancient Greeks balanced the Apollonian and Dionysian forces of the human mind. He believed that Dionysian myths and rites and their role in the evolution of theater offered ancient Greeks a means to break the shackles of social convention and transcend the moral illusions of culture by uniting with nature’s primal essence. Certain that Western culture has eulogized Apollonian principles of light, reason, control, and social norms and denigrated Dionysian ones of darkness, ecstasy, mystery, and the divine in nature, he argued that the forces, when balanced, create “new and more powerful births.” Though I disagree with some of his ideas and his first paradigm lacks the feminine impulse rooted in most Earth wisdom traditions, his vision of a balanced psyche supports my three-paradigm theory.

Vehemently, Nietzsche blamed the second paradigm’s imbalance on the Logos-dominant worldview that—in the hands of Socrates, Plato, Euripides, Church Fathers, and scientists—“demonized” and dissipated Dionysus. By helping Socrates deify morality and rationality, Euripides destroyed the aesthetic balance of Apollonian control and Dionysian energy by stipulating that reason alone offers an understanding of nature and a means to “better” it. Nature is not, Nietzsche implored, something to be dissected and “bettered.” He hated the Christian and scientific “urge to correct” nature and accused theologians and scientists of sustaining the great Western myth, namely, that the only proper relationship to life rests in the attempt to understand and improve it. The result, he insisted, has climaxed in a spiritual crisis that is still with us.

Nietzsche’s solution is to revitalize Dionysus and rediscover the sacred in the natural. This includes rescuing Jesus’ “true” message from the “gospel” one: the “Good News” is “found—it is not promised, it is here, it is within you; as life lived in love, in love without deduction or exclusion, without distance. Everyone is the child of God—Jesus definitely claims nothing for himself alone—as a child of God everyone is equal to everyone else.” Nietzsche also insisted that we need to recognize “truth” as relative (one of the reasons he’s considered the first postmodernist). A highly problematic part of his solution is the Übermensch, the “Higher-human” or so-called “Superman,” the qualities of which are immersed in patriarchal traits, values, and “master morality.” Using an increasingly ominous Dionysus as a model for the ideal man, Nietzsche encouraged amorality, the will to power, and a transvaluation of values “beyond good and evil.” Despite anger-driven views, his original imperative that we need to balance the human mind helps explain his contemporary relevance and why his vision can be interpreted as ecocentric; because whatever you may feel about it, Dionysian spirituality and its reverence for instinct, ecstasy, and nature remains a link to Earth wisdom traditions that are still part of the Western ethos.

One repays a teacher badly if one always remains nothing but a pupil.

The surest way to corrupt a youth is to instruct him to hold in higher esteem those who think alike than those who think differently.

He who would learn to fly one day must first learn to stand and walk and run and climb and dance; one cannot fly into flying.

— Friedrich Nietzsche

I had other superb classes at Eckerd such as Psychology of Consciousness and Philosophies of the East and wrote a very ambitious senior dissertation in which I tried to synthesize my emerging worldview. My Eckerd experience ignited an unending passion for learning. I also had a great season playing basketball and, with new ambitions, headed to Europe where, while playing hoops, I wrote A Matter of Perspective and studied Icelandic at the university, audited a Humanities class in Munich, was accepted as a Master’s student in philosophy at Bamberg, and took a class called Mysticismus. But first I had to pass the German exam, which was no small feat. My translation section on the exam was a long citation from Einstein! My wife Ulli will be the first to admit that at the time my grammar was better than hers. The class was small and we sat in a circle twice a week in the professor’s office. We read and discussed lots of handouts and had only one assignment all semester: a project that we had to write and present. There were no grades, you either passed and got a “Schein,” a certificate, or failed.

I did my project on Cultural Transformation Theory and focused on Fritjof Capra’s book Wendezeit (The Turning Point) and, of course, the three paradigms. In his first book, The Tao of Physics, Capra compares Eastern esoteric teachings and descriptions of the quantum world, and in the process, learns to apply the Chinese notions of yin and yang as a model to address a systemic cultural imbalance. Echoing Alan Watts, The Turning Point contends that the West’s yang-oriented, mechanistic worldview is being reshaped by a yin-based, organic one grounded in earth-centered spirituality. The reshaping is evidenced by the rise of human rights, feminism, environmentalism, and related movements that accompany shifts emerging in science, psychology, economics, health care, energy consumption, and ecological relations. I realized the project’s ridiculously huge scope while trying to defend it in German against a barrage of questions from very astute, pragmatic German philosophers (i.e., eight students ranging from age 25 to 65). It went surprisingly well and my professor was pleased.

I never teach my pupils; I only attempt to provide the conditions in which they can learn.’ – Albert Einstein

Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world. — Nelson Mandela

Wisdom is not a product of schooling but of the lifelong attempt to acquire it. — Albert Einstein

“The only person who is educated is the one who has learned how to learn and change.” — Carl Rogers

Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn. — Benjamin Franklin

Of course, living and traveling throughout Europe and elsewhere (including Greece and Egypt) for eight years was an education in itself, but after reaching 30 I realized I wanted a career in education. So I took my GREs, enrolled in an Interdisciplinary Humanities Master’s program (exactly what I was looking for), and we left Germany for the University of West Florida. We loved Pensacola and made it to the beach often. We lived on campus in a married housing dorm and made a lot of lifelong friends. My studies were everything I’d hoped. Philosophy, Religion, and Art History were my areas of concentration. The program director, Robert Armstrong awarded me a grant and his Humanistic Understanding seminar was great. We would read a book, take notes on it, and lead a discussion based on major ideas. I remember mine: Ken Wilber’s Eye to Eye: The Quest for the New Paradigm, Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Alan Watts’ Nature, Man, and Woman, and The Only Dance There Is by Ram Dass. I also enjoyed my American Romanticism and art history courses, but my Philosophy of Comparative Religion was a game changer. I wrote a paper on “The Spirit of Ecology” and coalesced various deep ecology and ecofeminist perspectives into my own. Environmental philosophy has remained a mainstay in my approaches to learning and teaching.

If I had to pick a favorite class, however, it would be Religion and Personality Theory. Among other books, we read Jim Fowler’s and Sam Keen’s Life Maps, and one day the professor, my friend, mentor, and dissertation director, Barry Arnold, decided that he and I would role-play the authors. The two of us sat in the middle of the customary circle and I donned Keen’s Dionysian attitude and countered Barry’s/Fowler’s Apollonian claims and questions in hearty and spontaneous ways. It was fun and my colleagues were amused. Not surprisingly, my dissertation was on balancing cultural expressions of nature’s polarities, which focused on Dionysus/Shiva/yin and Apollo/Vishnu/yang and ways in which the feminine, ecological impulse of Earth wisdom traditions is being integrated into the West’s dominantly patriarchal cultures. Needless to say, Ulli and I loved our two years there, which climaxed with the birth of our twins, Jeremy and Julia, near the end of the final semester. Feeling blessed, I accepted a graduate teaching assistantship at Florida State University and went straight into their Ph.D. program in Interdisciplinary Humanities.

Our time in Tallahassee was a bit more challenging but equally fantastic. My areas of concentration included Classical Culture, Asian Studies, and Philosophy. Two of my Classical Culture courses were taught by Dr. Golden, the program director. He completely changed the way I look at Homer’s Illiad and Vergil’s Aeneid. Despite what has been taught for centuries, both works are anti-colonial and anti-Heroic Code! Homer warns us right away that Achilles’ pride and ruinous rage “put pains a thousand-fold” on his comrades. He pierces Hector’s feet and drags his dead body behind his chariot around the walls of Troy while screaming desecrations. On the other hand, Homer portrays Hector, an enemy of Greece, as a wonderful son, brother, husband, father, and warrior. He wants us to feel the inhumanity of Achilles, Greek colonialism, and war in general. That’s why he describes deaths so horrifically. Warriors have their bloody guts spilled onto the earth, dark red bowels pool here and there, eyes are poked through brains and stuck on ends of spears, and so on. While many of the dead warriors are left nameless, 240 are identified and Homer reminisces on their unfilled lives, such as Simoisius, whose mother bore him along the banks of the Simois River, who would no longer tend sheep with his parents. Sure, Achilles relented and gave Hector’s body back to Priam, but Homer is still clearly saying that the Heroic Code and conquering hero are not what they’re made out to be. Vergil makes the same point (with no signs of redemption!) with Aeneas in The Aeneid. In the epic’s last lines, Aeneas kills the aboriginal Turnus—who is unarmed and lying on his back—by stabbing him in the chest “in furor”; exactly the opposite of what his Father Anchises told him to do in their underworld meeting. He told him to tame the proud, never act in furor, and always spare the conquered, which Aeneas doesn’t do. Why? The same reason Vergil has Anchises send Aeneas out the gate of “false dreams,” and not the gate of “true shades.” There are many more examples that, admittedly, I would not have looked for if it weren’t for Professor Golden. Moreover, he made a great case for how and why Vergil coded his anti-Augustan message into the book, a case that is both extensive and convincing.

Of all my classes, two of the most demanding were four semesters in Chinese with Dr. Lu and a directed study called “Readings in Yin and Yang” with Ruth Katz. The main reason I took Chinese was that I wanted to translate the Daode jing, one of my favorite books ever. I have 12 translations and you wouldn’t believe how different they can be. For the other class, I read as much as I could on the evolution of yin, yang, and the Dao—from their shamanic origins and classical expressions to their contemporary relevance. Ruth’s specialty was Hinduism, but she also loved Daoism. While she and Dr. Golden were two of my favorite professors, David Darst was my main mentor. I had him for two humanities classes–Medieval to Baroque and Love and the Occult in the Renaissance–and he chaired my dissertation committee. I am grateful to a lot of teachers and many of them became good friends, but David and I have stayed in contact for over 30 years and no one taught me more about teaching than David. We had some amazing parties with colleagues, professors, and other friends, and David never missed one.

My dissertation was a major extension of the one I wrote for my Master’s. After I graduated I morphed part of it into the 1994 book, The Balance of Nature’s Polarities in New-Paradigm Theory, and then into Renewing the Balance almost 25 years later. It remains my conviction that we are in the midst of a potential cultural transformation that aims at balancing the dominant masculine, technological yang drive with the feminine, ecological yin impulse on individual, social, and planetary levels. I cannot tell you how many hours I spent in FSU’s Strozier Library or how many books I checked out (there was no googling back then). Ecofeminists such as Carolyn Merchant and Charlene Spretnak, cultural historians such as Theodore Roszak, ecophilosophers such as Thomas Berry, and deep ecologists such as Bill Devall and George Sessions are just a very few of the scholars who share my conviction that a true cultural transformation demands the realization that social and environmental problems stem from the same source, namely, the pathological separation of nature from human nature. By reconnecting to biophilia and sensing the spiritual in the natural, we can reconstitute legal, political, and economic relations between human societies and rectify our attitudes and activities that harm other species and burden the health of the planet and our collective spirit.

Education is the best weapon for peace.

The work of education is divided between the teacher and the environment.

[T]he teacher’s task is first to nourish and assist, to watch, encourage, guide, induce, rather than to interfere, prescribe, or restrict.

This is the hope we have—a hope in a new humanity that will come from this new education, an education that is collaboration of man and the universe.

— Maria Montessori

My Life as a Teacher

I taught four different courses while at FSU–three chronological sections on humanities and one on Multi-Cultural Dimensions of Film Art in the 20th Century. I knew right away I would love teaching. My first course, Intro. to Humanities part one, was extremely broad, but I relished the odyssey of exploring cross-cultural traditions and triggering student insights and sensitivities relating to art, philosophy, religion, politics, and everything else human. We breezed over Paleolithic and Neolithic periods and skimmed Mesopotamian, Indus Valley, Chinese, Egyptian, Mesoamerican, and Old Europe cultures. From the invention of the wheel, the origin of writing, the Venus of Willendorf figures, Hammurabi’s Code, and the Yijing, to the pyramids, we zoomed through periods of cultural transformation picking particular events and achievements that elicit wild things like Zeitgeists and human potential. We hit cultural hot spots from the Bronze Age and Homer, Minoans and Mother Earth worship, the polis and Greek philosophy to Hellenism, and the rise of Roman culture. We covered Hebrew culture and wisdom literature (e.g., Job and Ecclesiastes), Jesus’ teachings, Paul’s theology, the spread of Christianity, the hypocrisy of Augustus’ Pax Romana, and the wonders of Stoicism, the Pantheon, and the Aeneid. We jumped from the Byzantine Empire to Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian cultures, from Augustine, Justinian, and the rise of Islam to Charlemagne, Monasticism, feudalism, and the Song of Roland, from the Romanesque style and Gregorian chants to manuscript illumination, the Crusades and Inquisitions to Aquinas and scholasticism, Giotto, Dante, and the Plague, and, finally, from Gothic architecture to the “new humanism.” See what I mean, the course is overly comprehensive. We talked about tons more in the class and the topics themselves seem so random when I discuss them here.

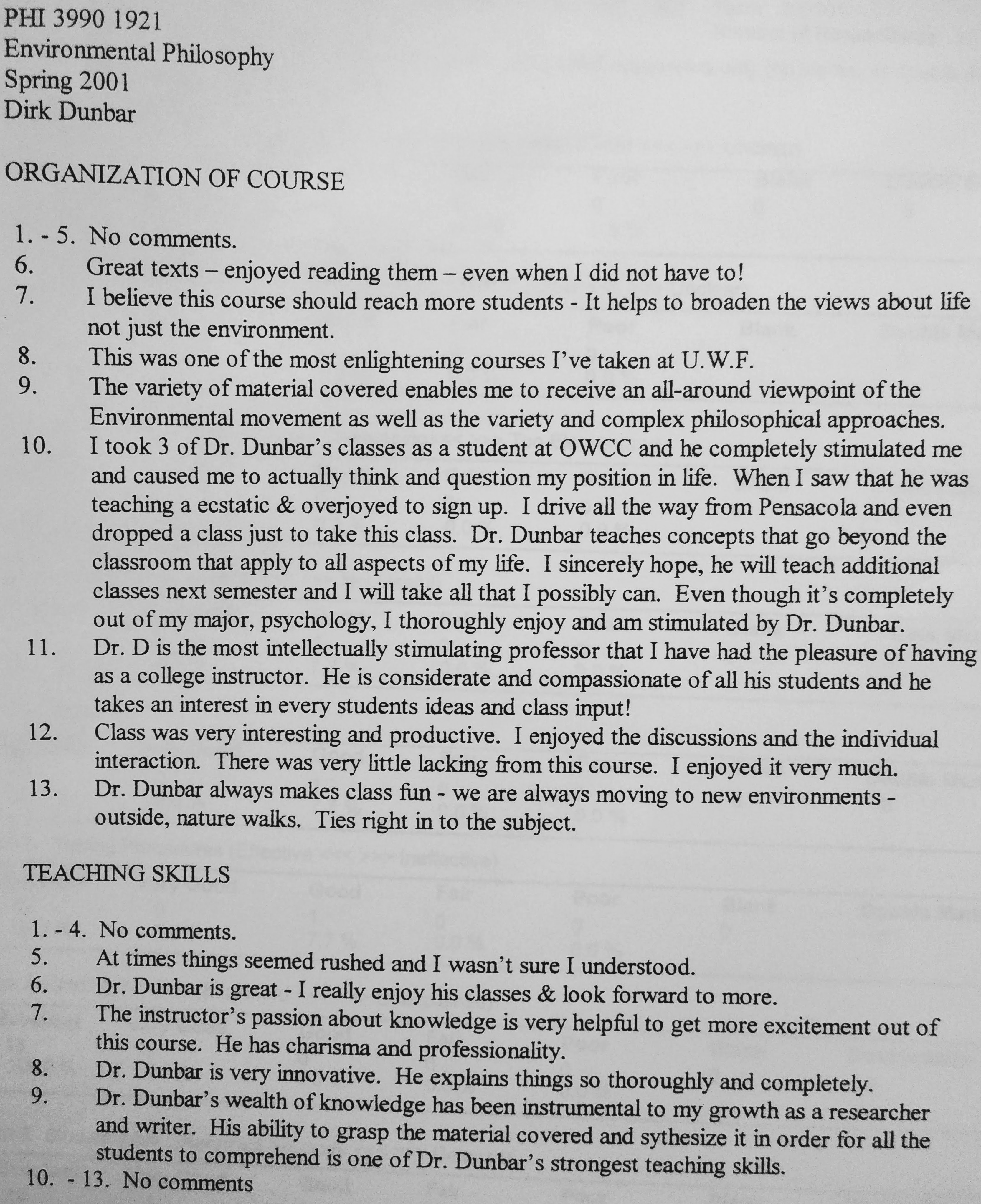

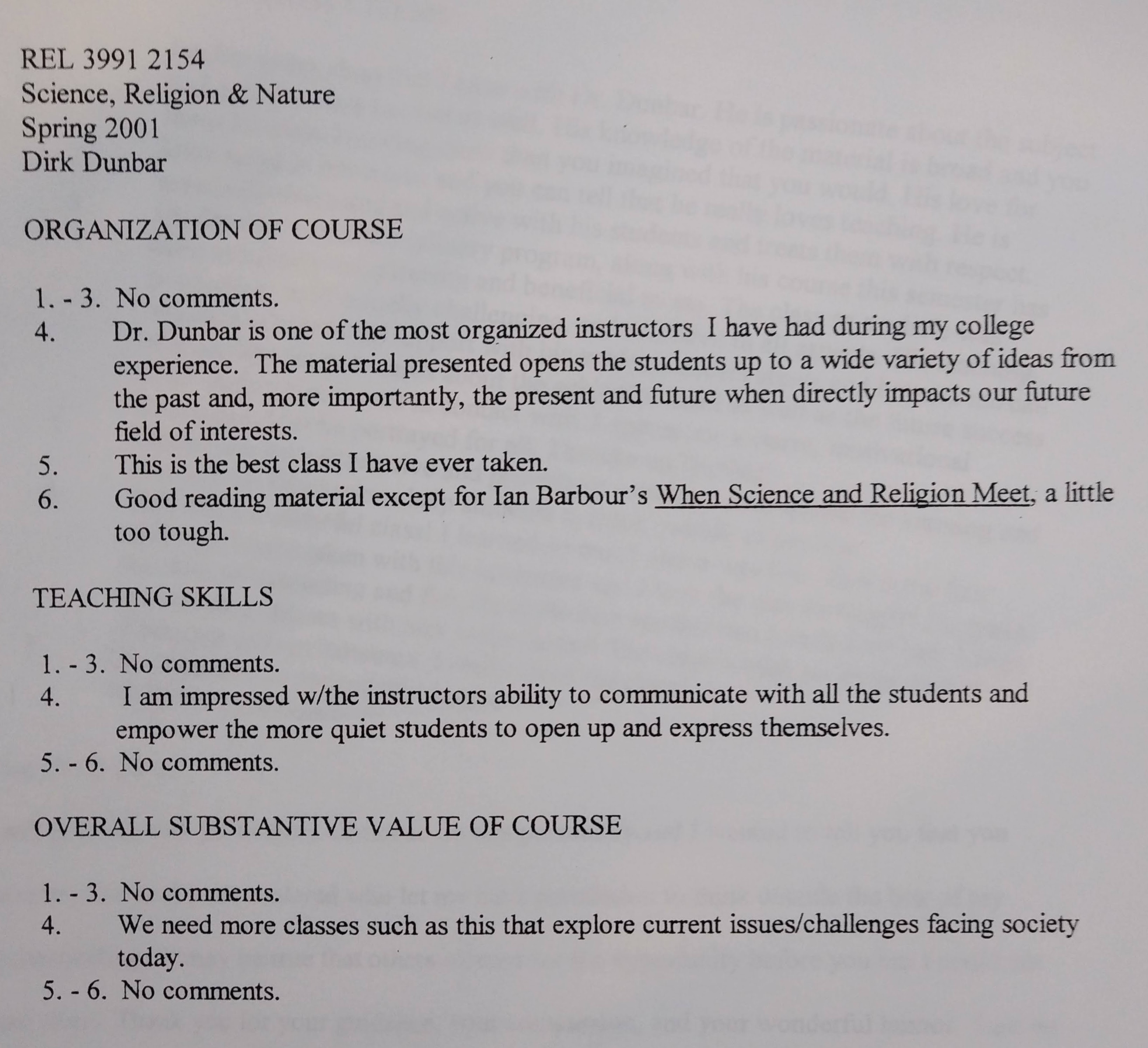

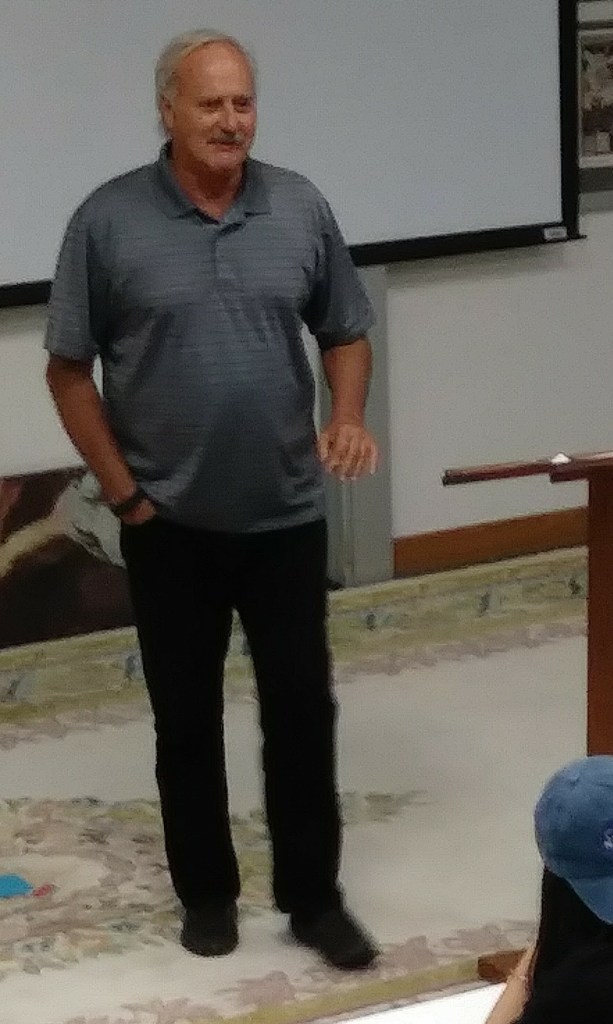

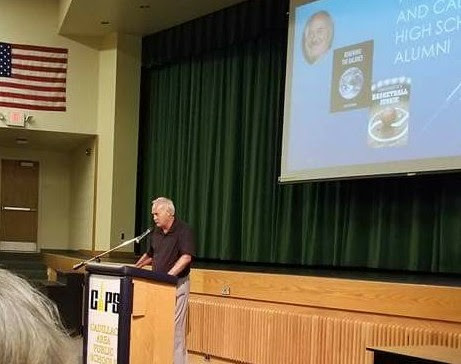

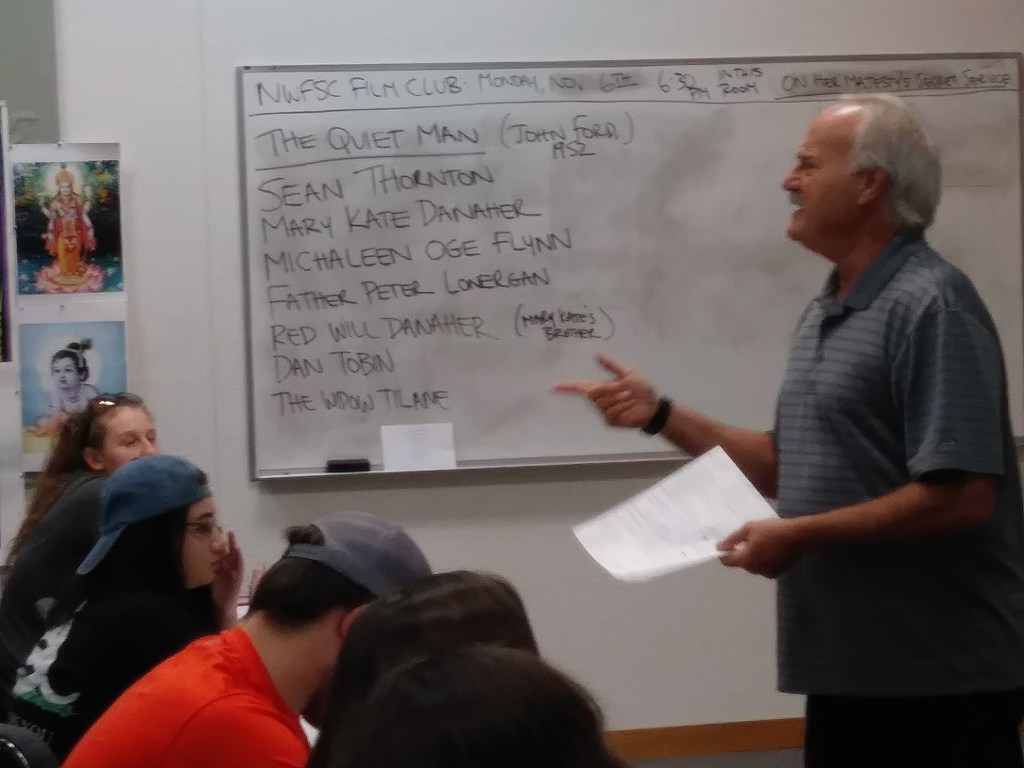

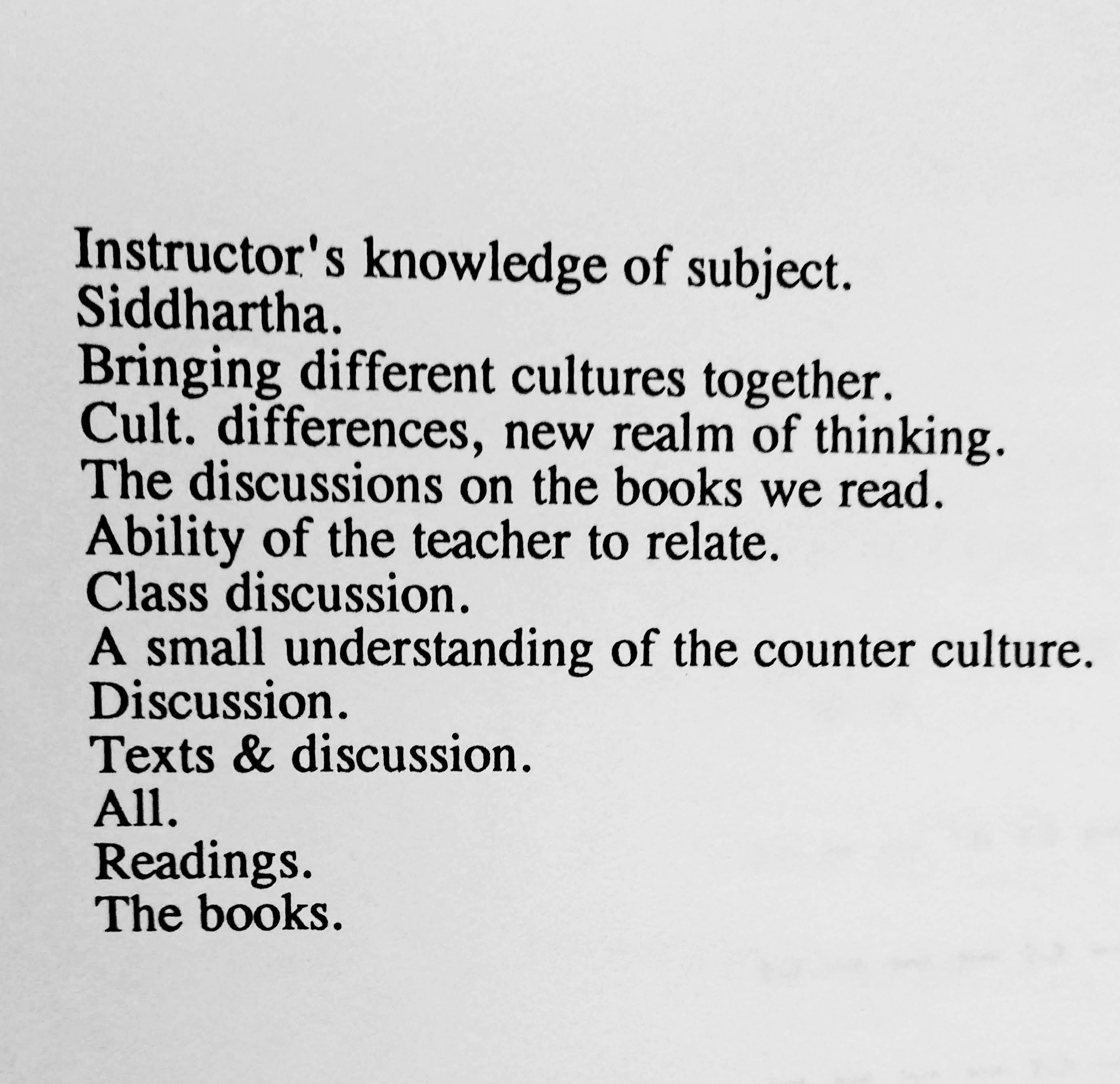

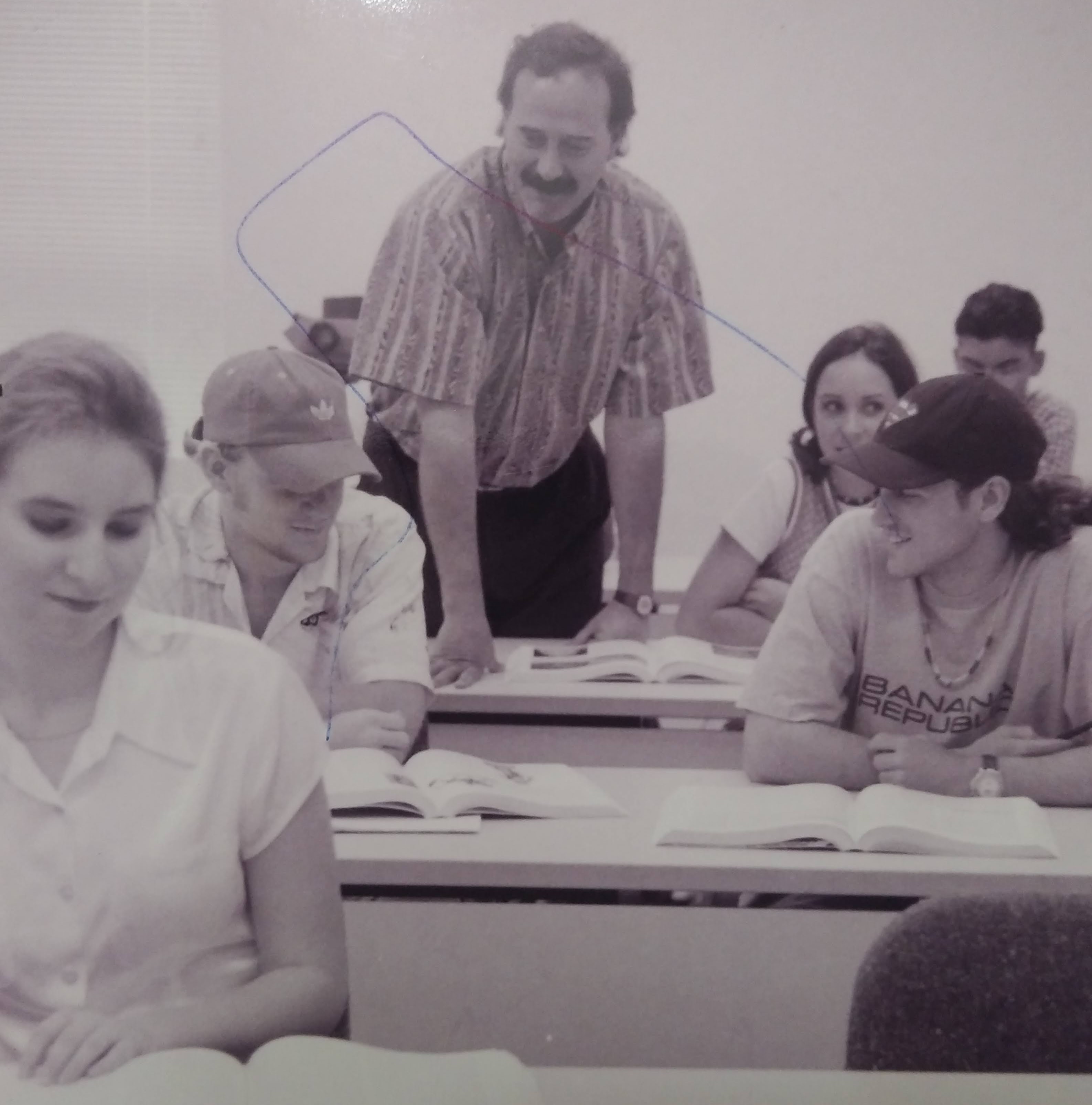

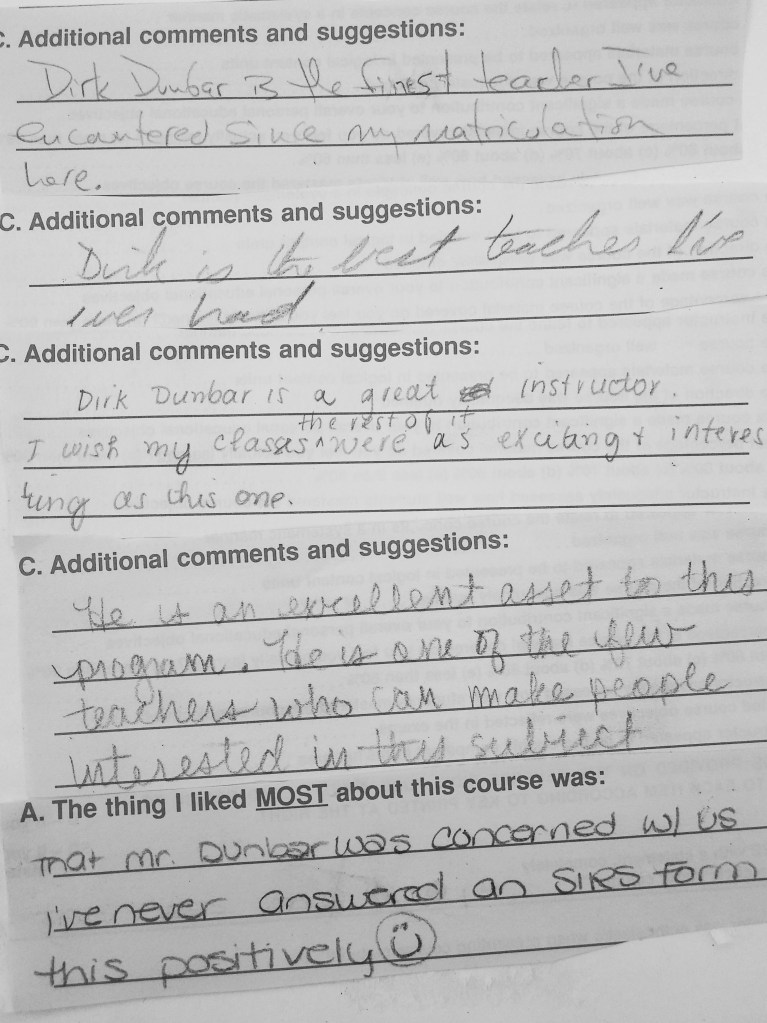

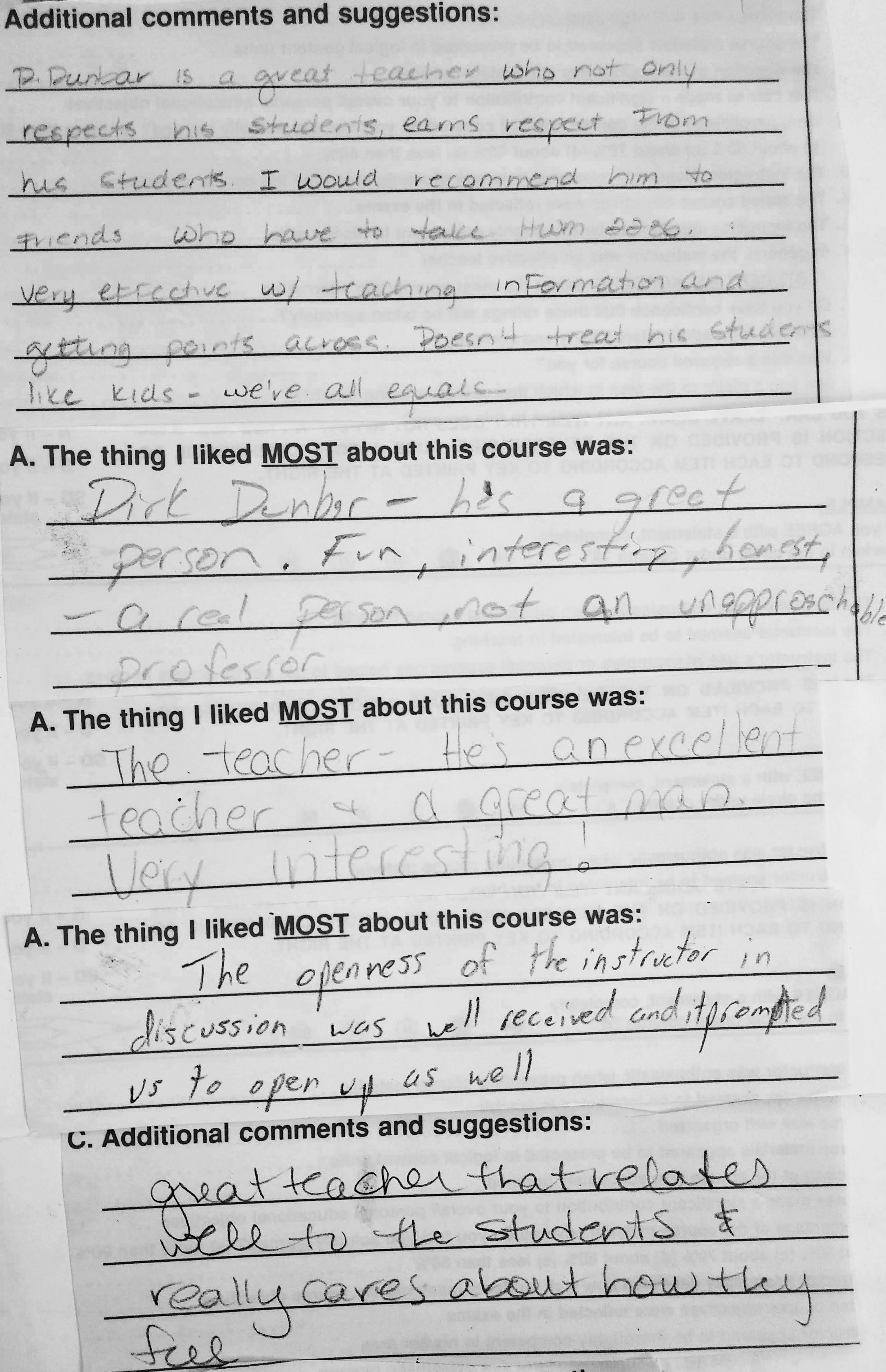

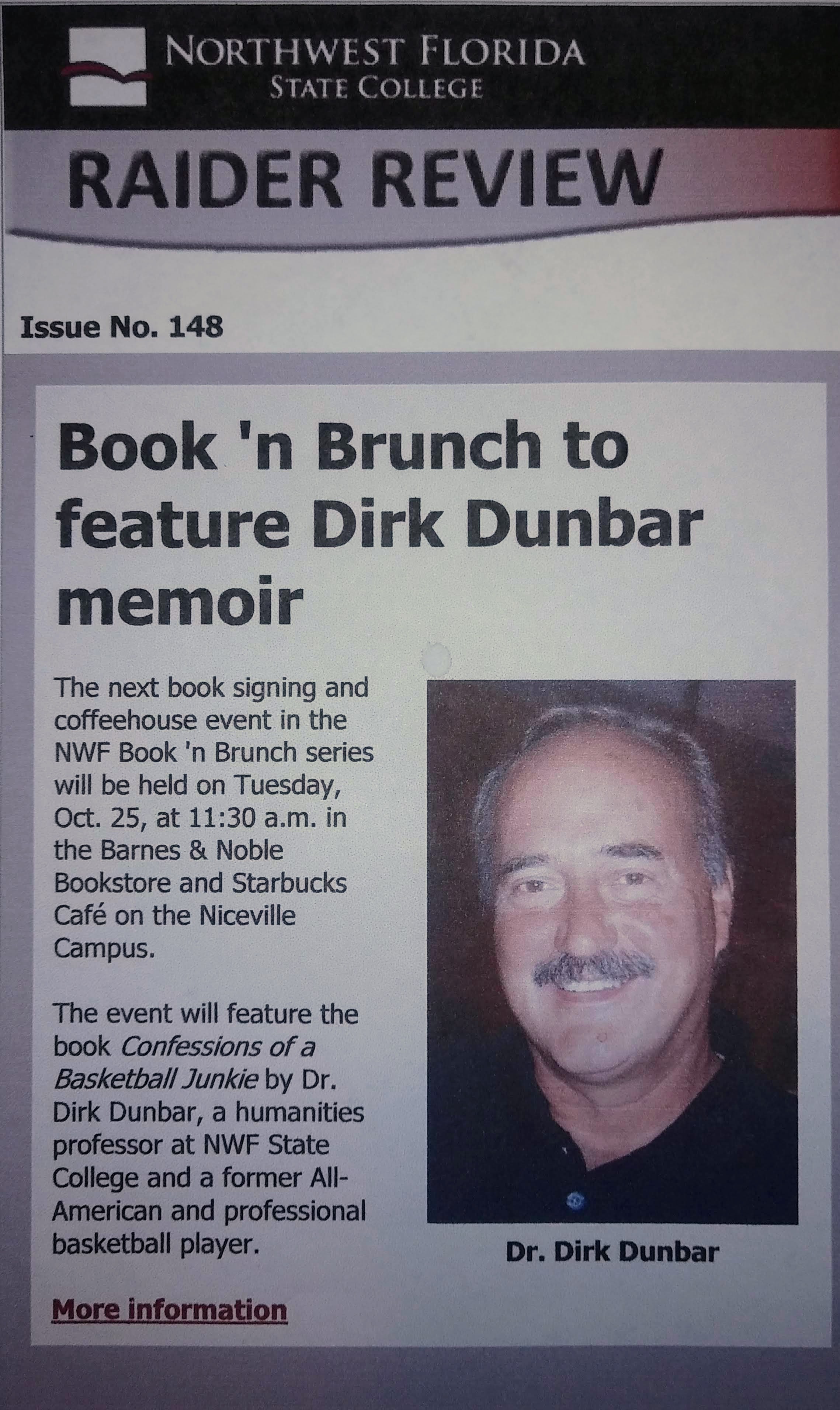

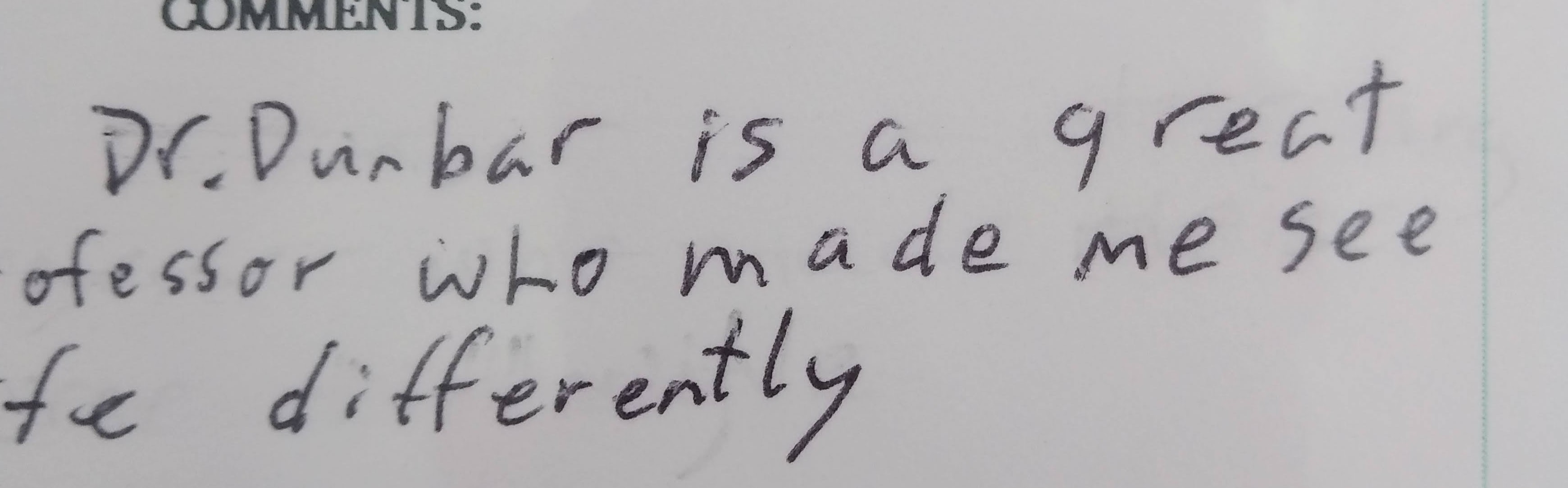

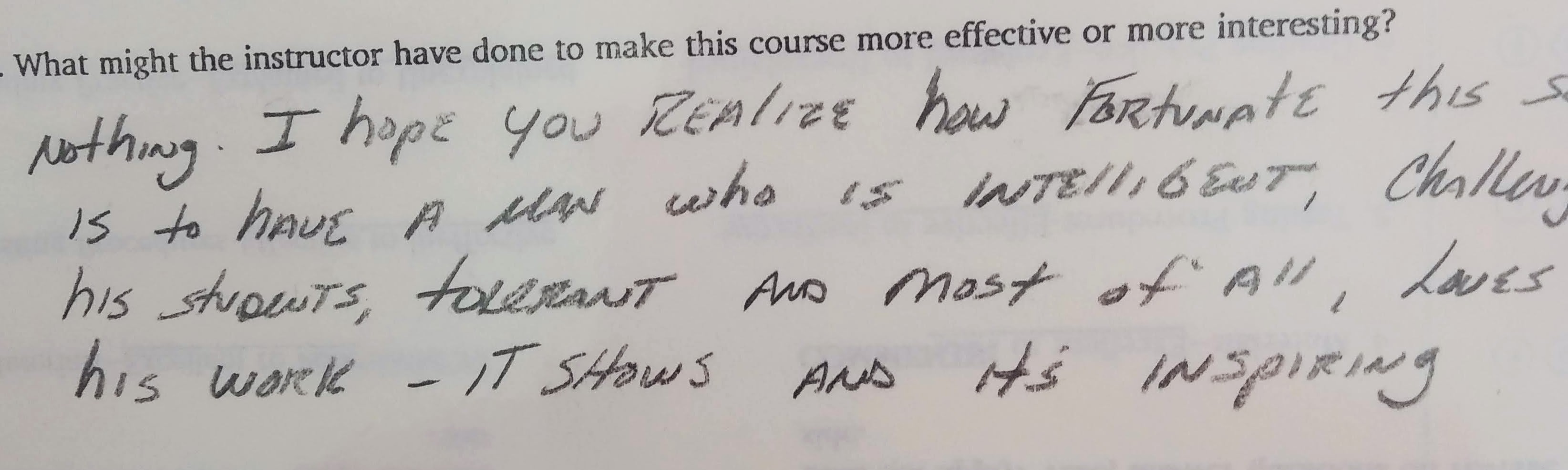

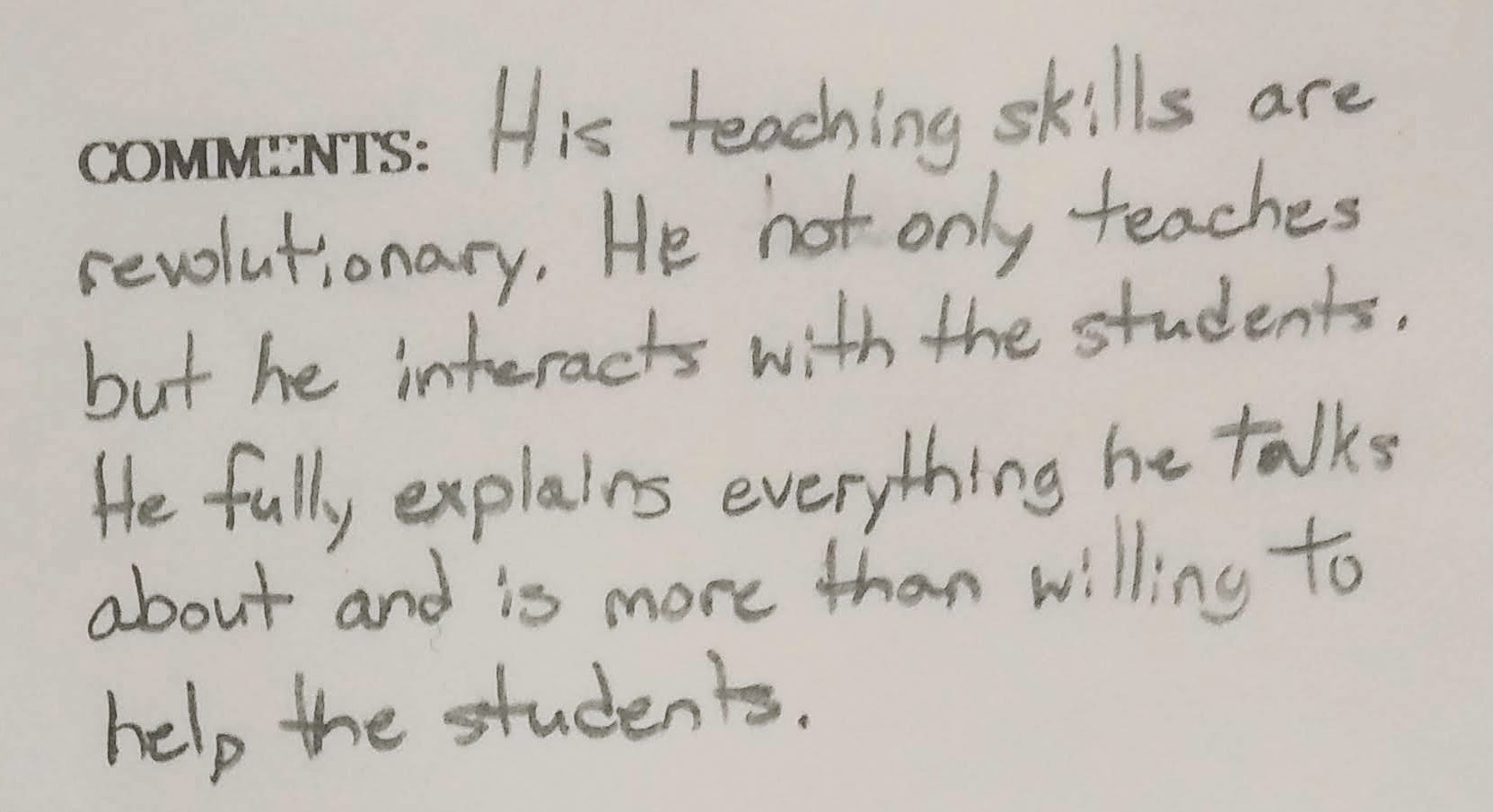

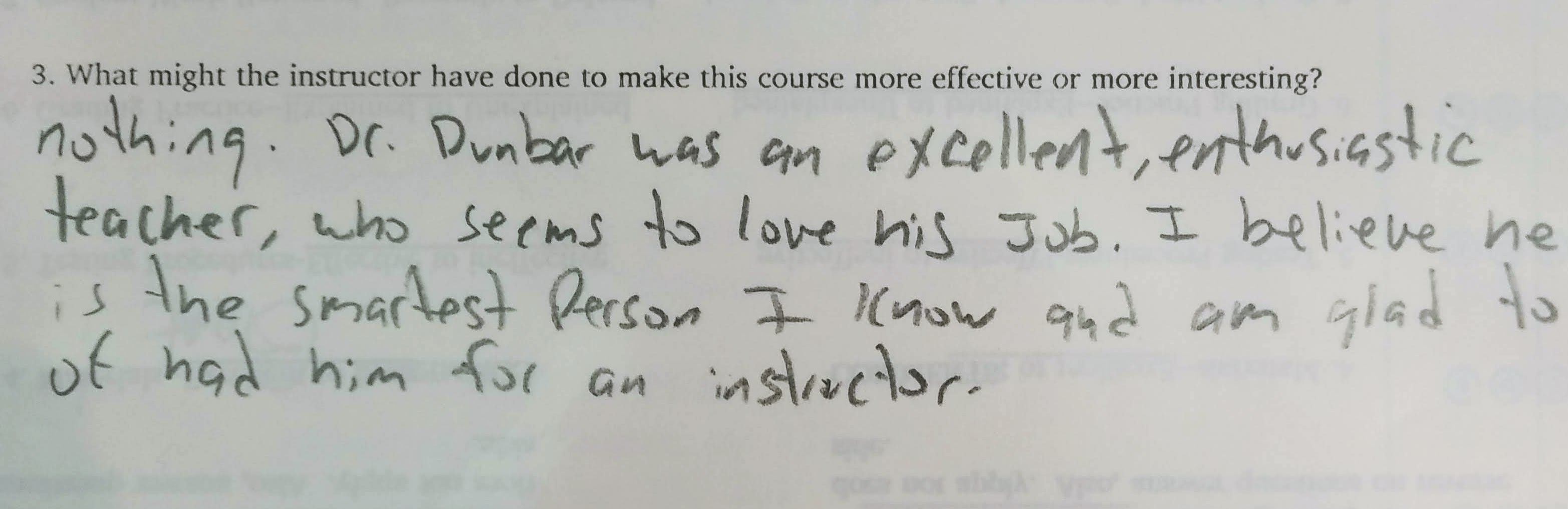

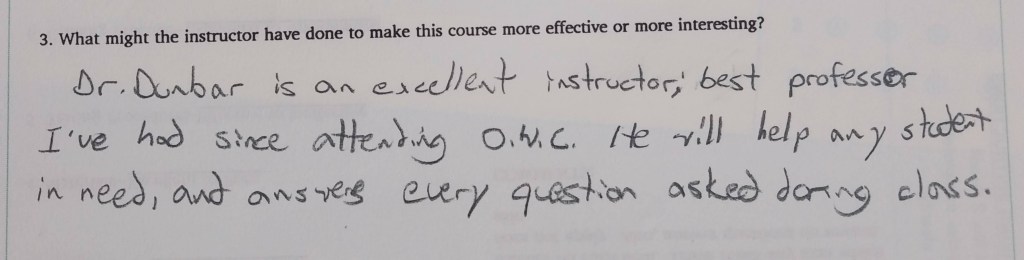

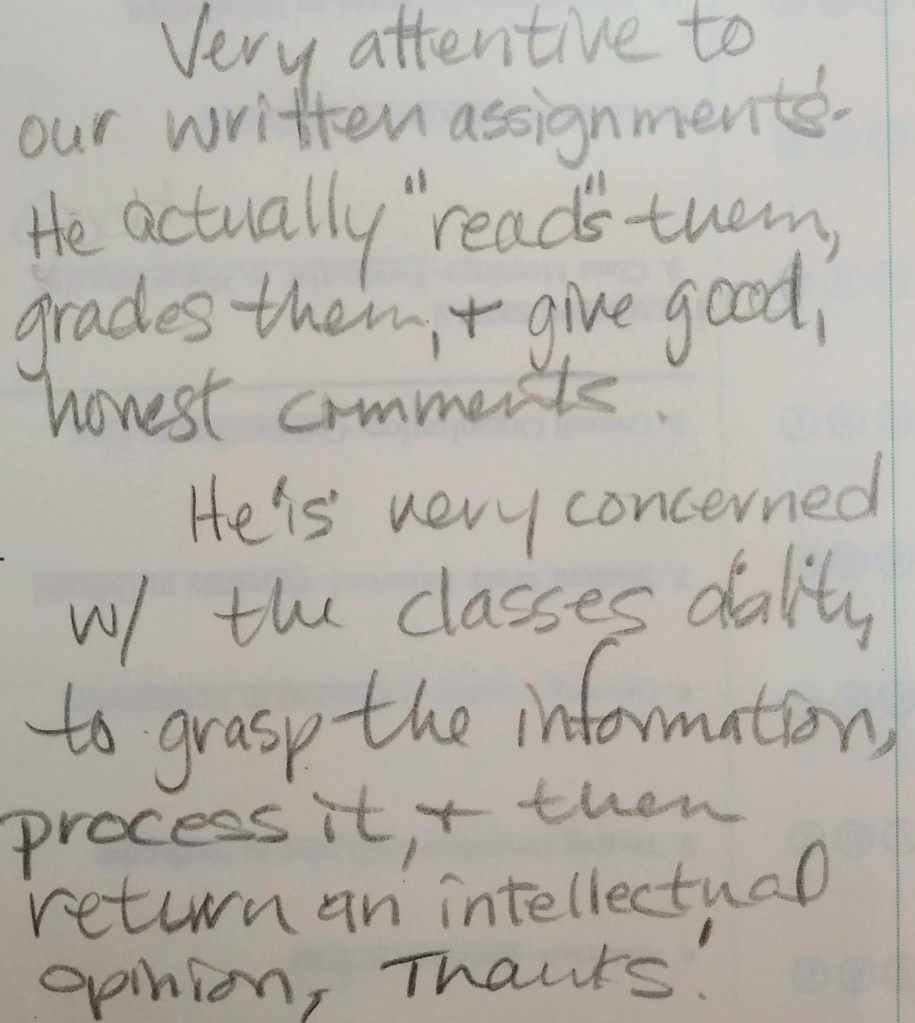

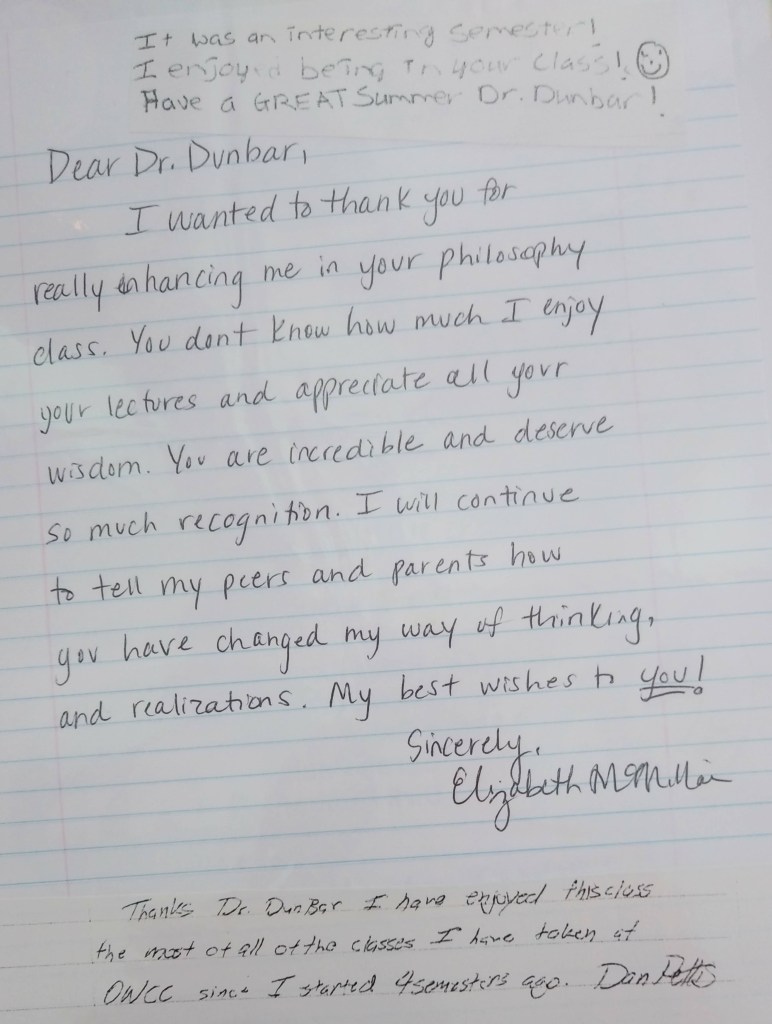

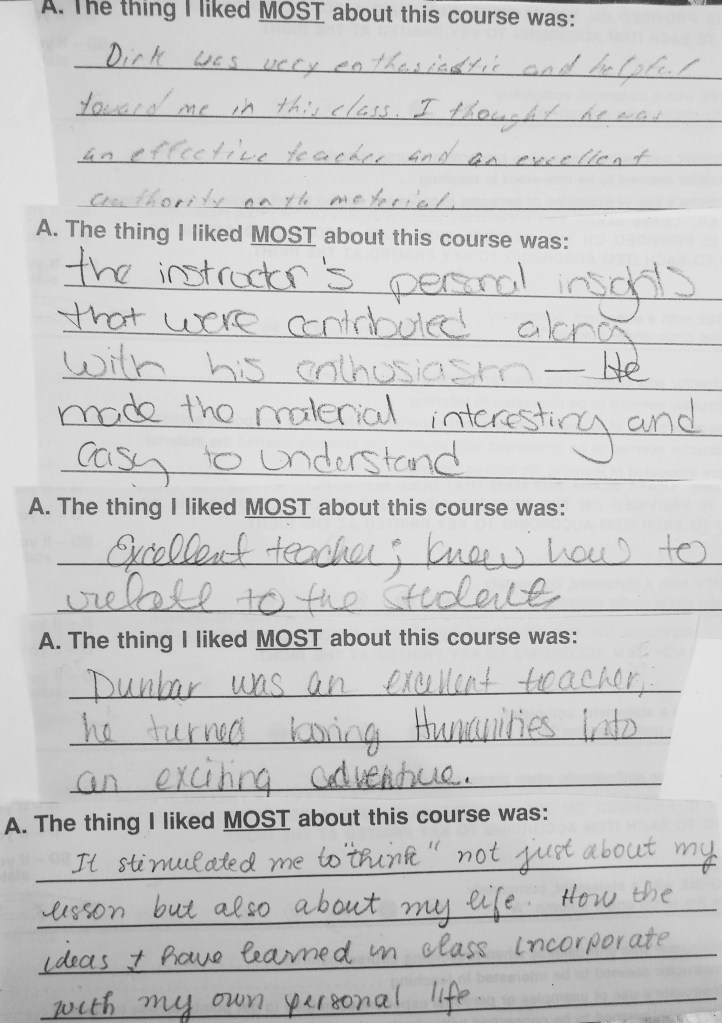

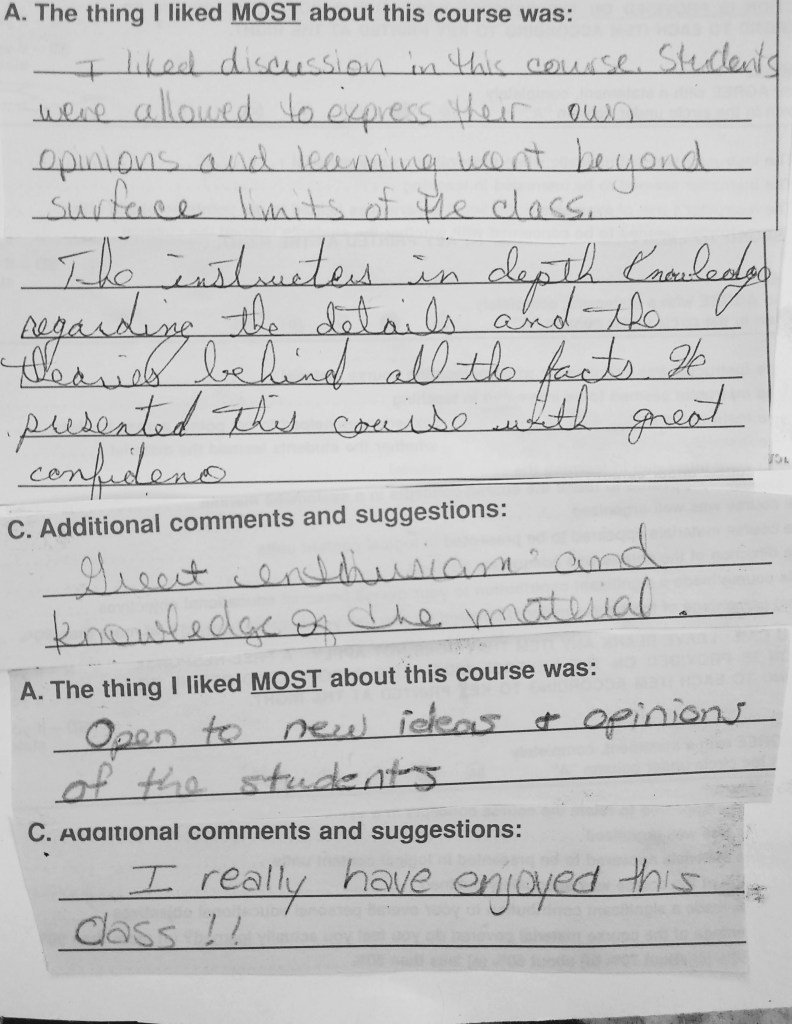

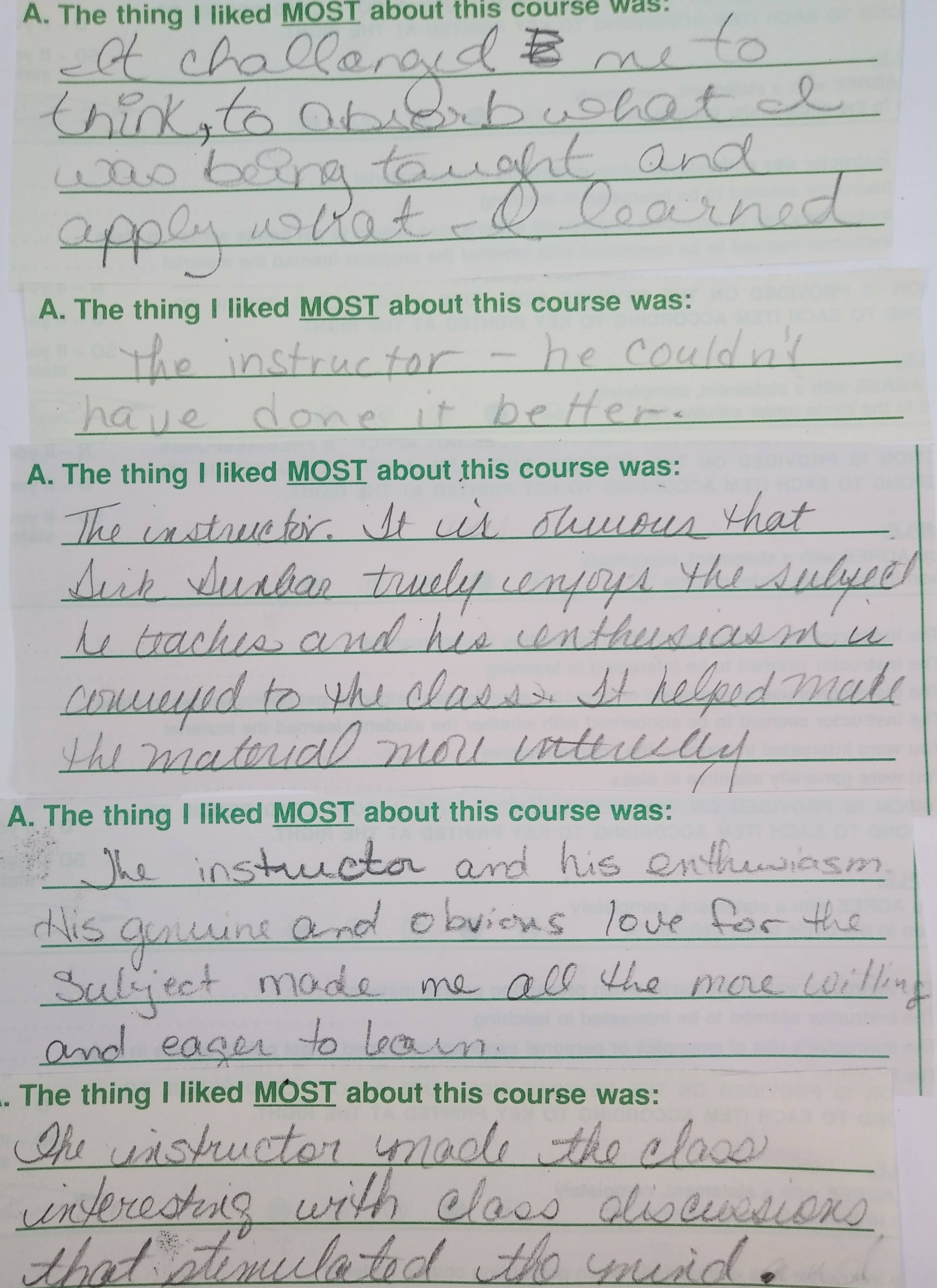

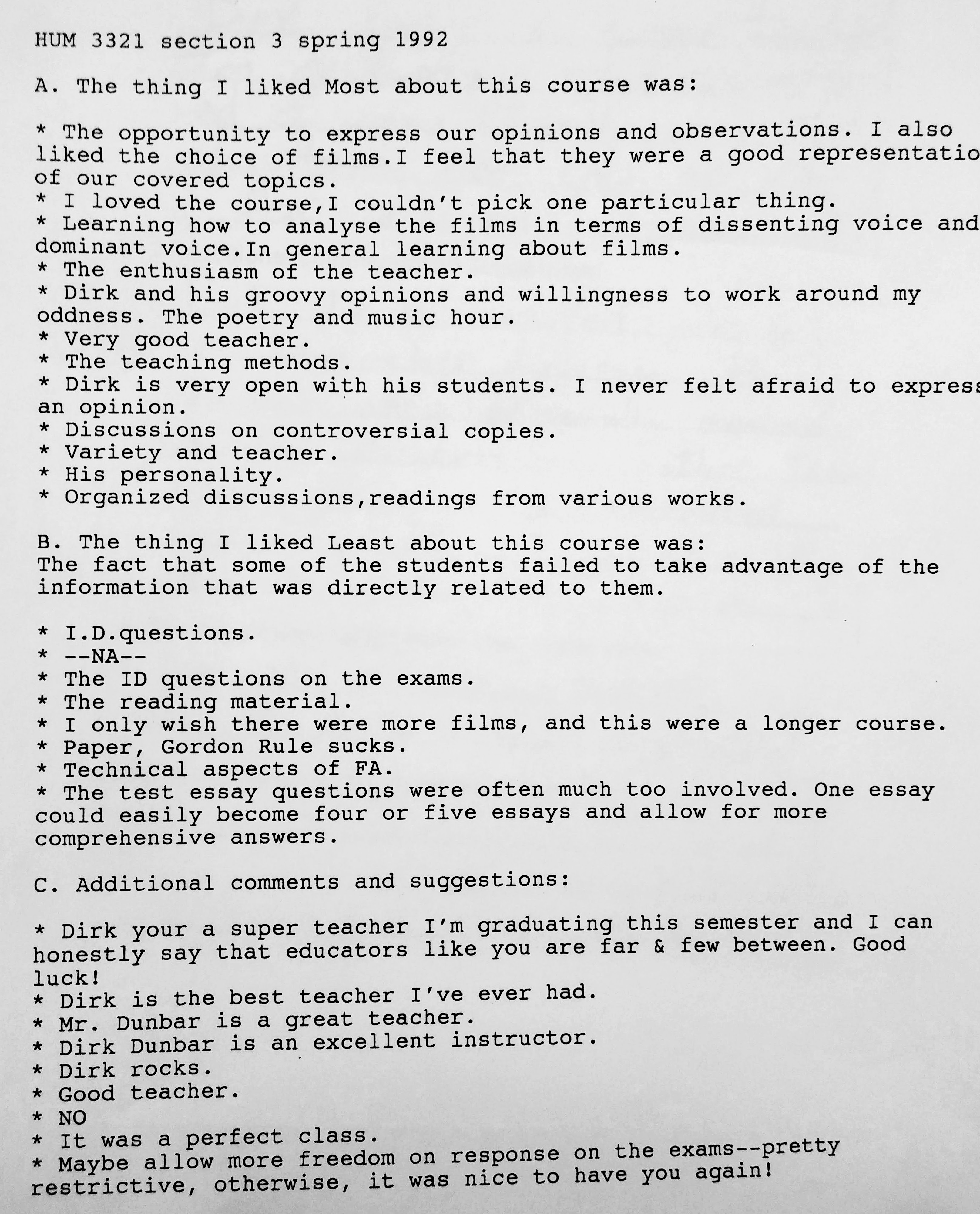

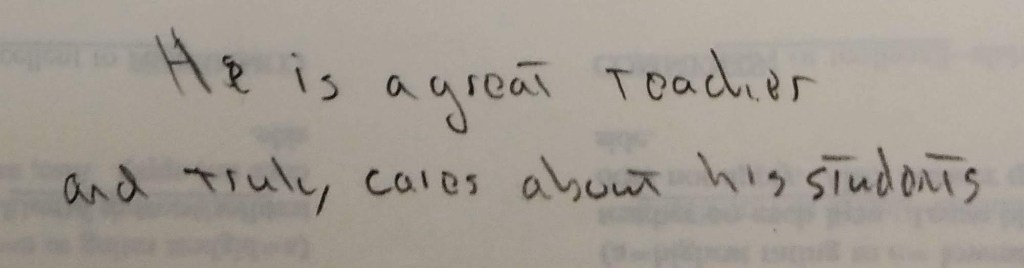

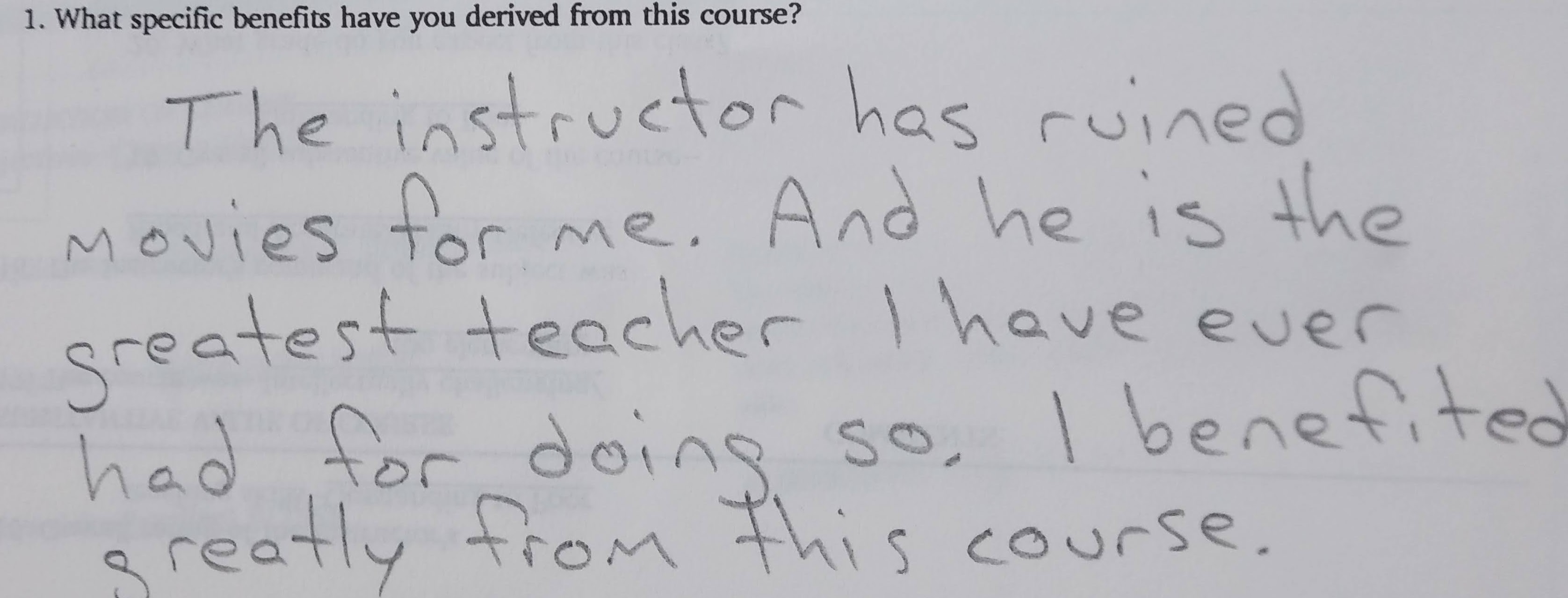

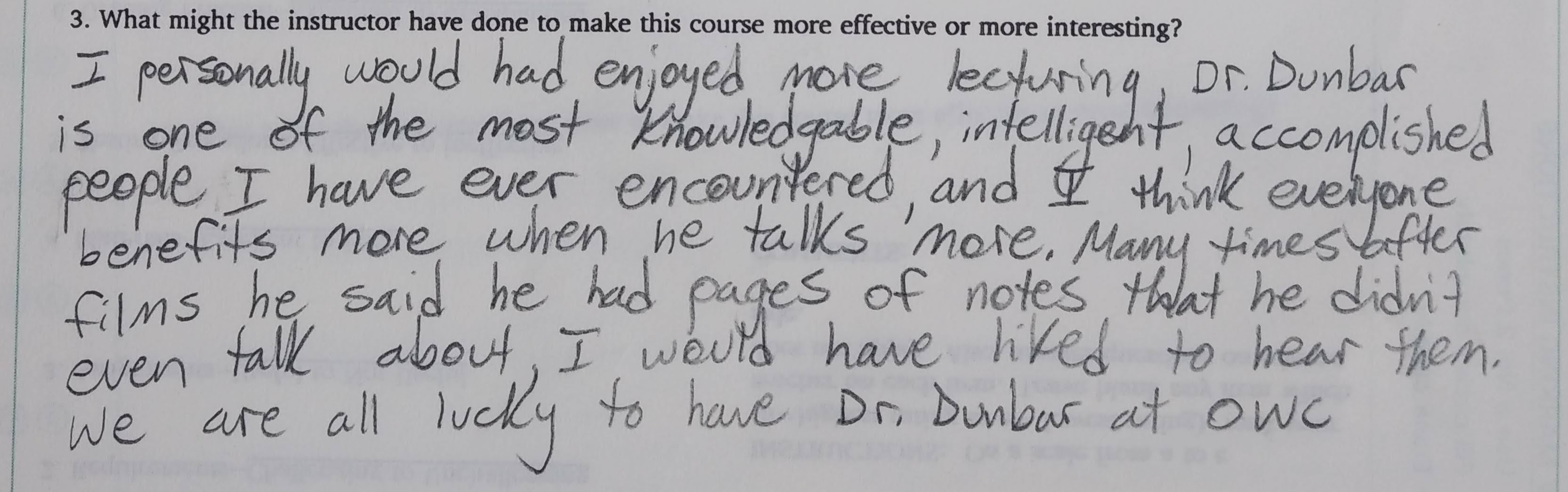

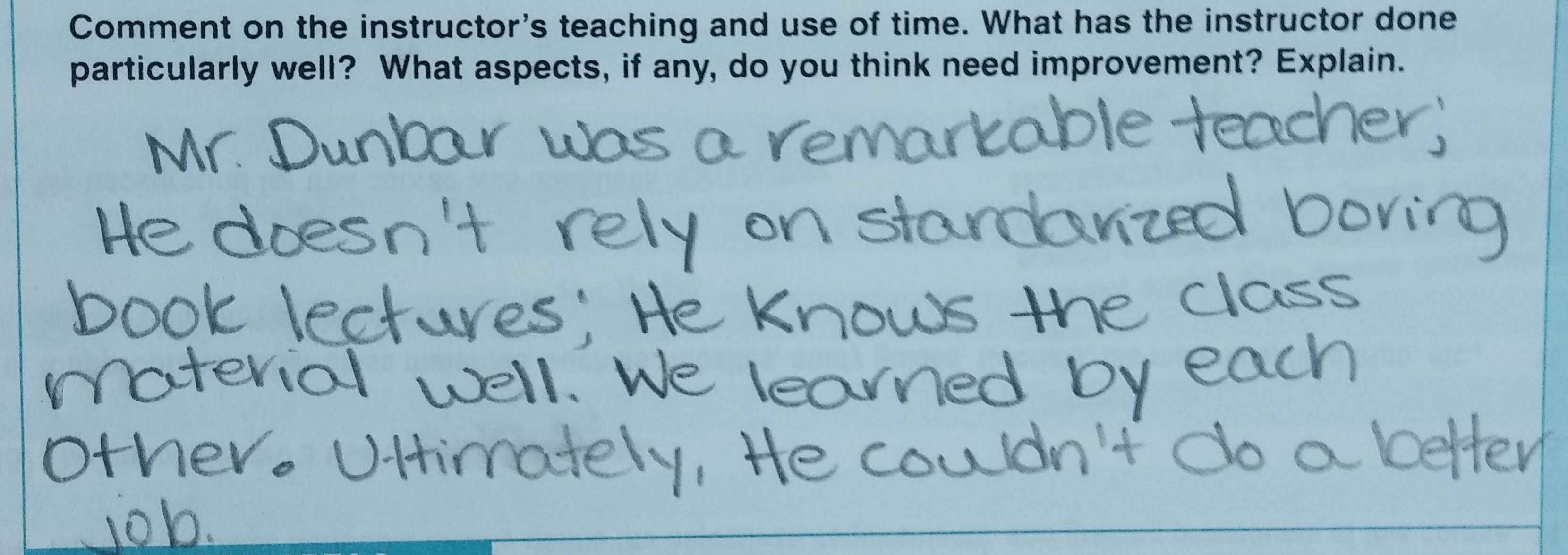

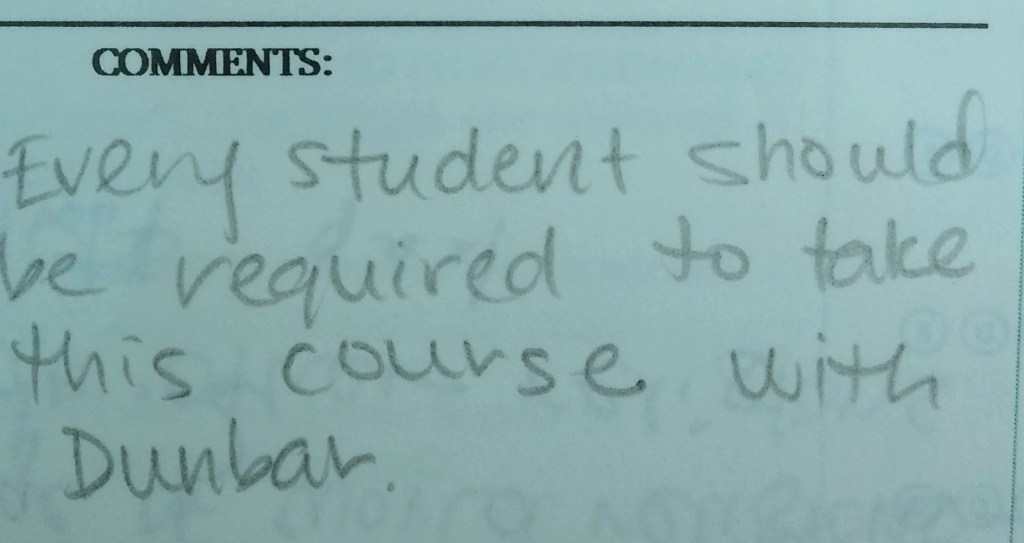

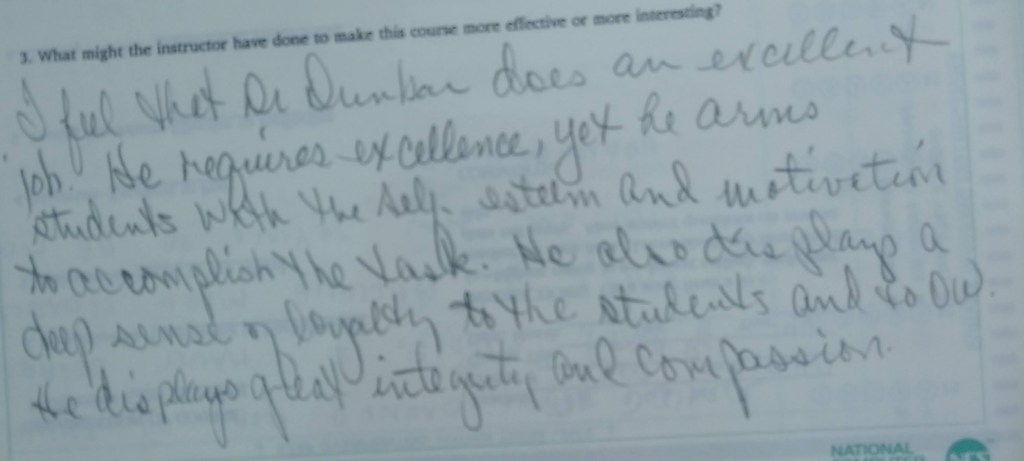

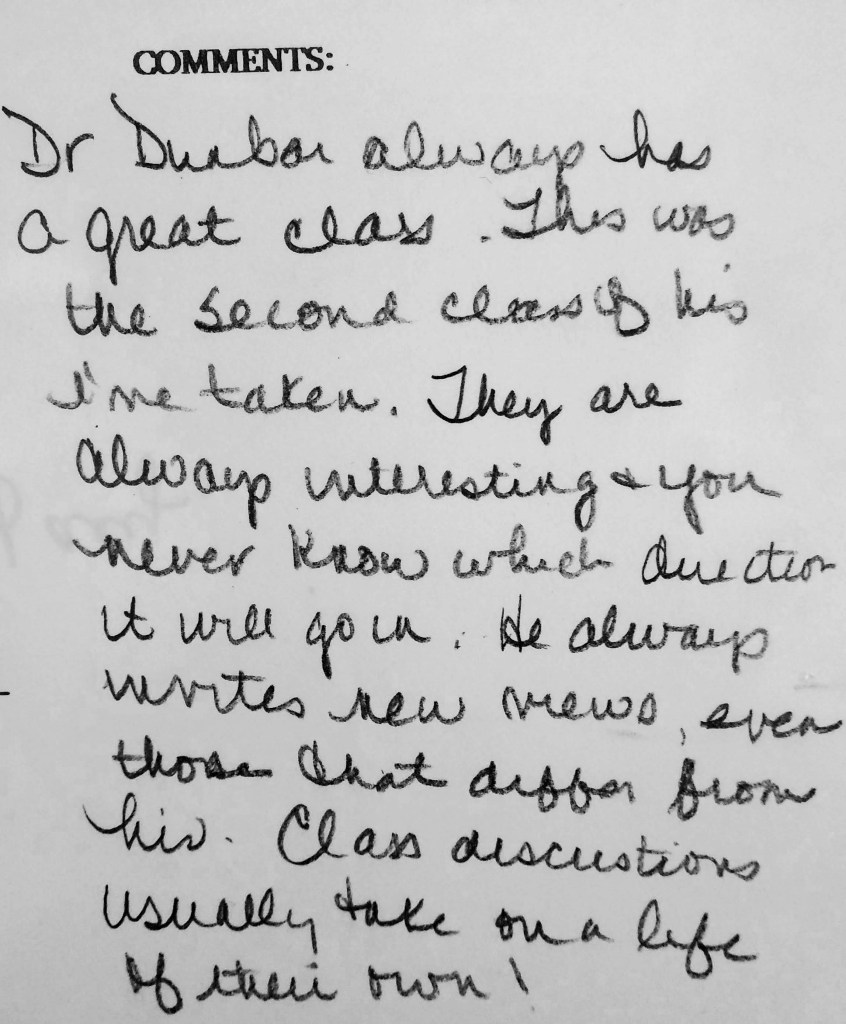

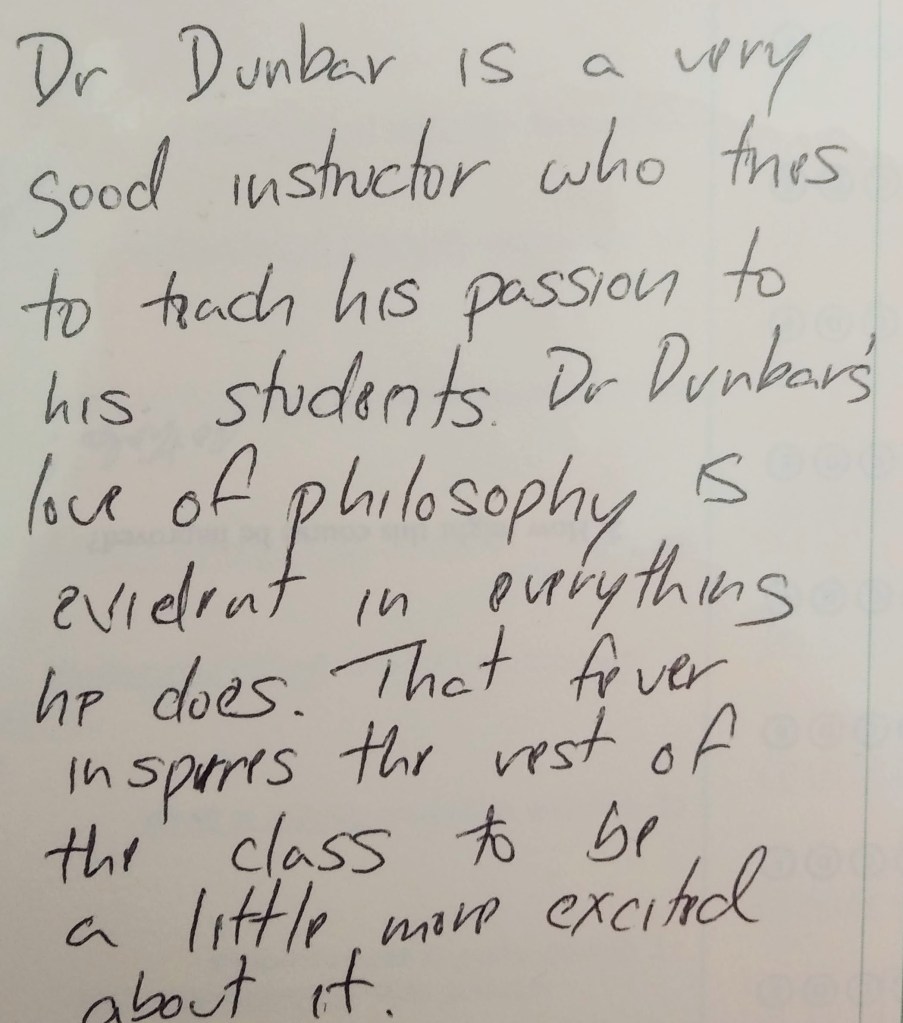

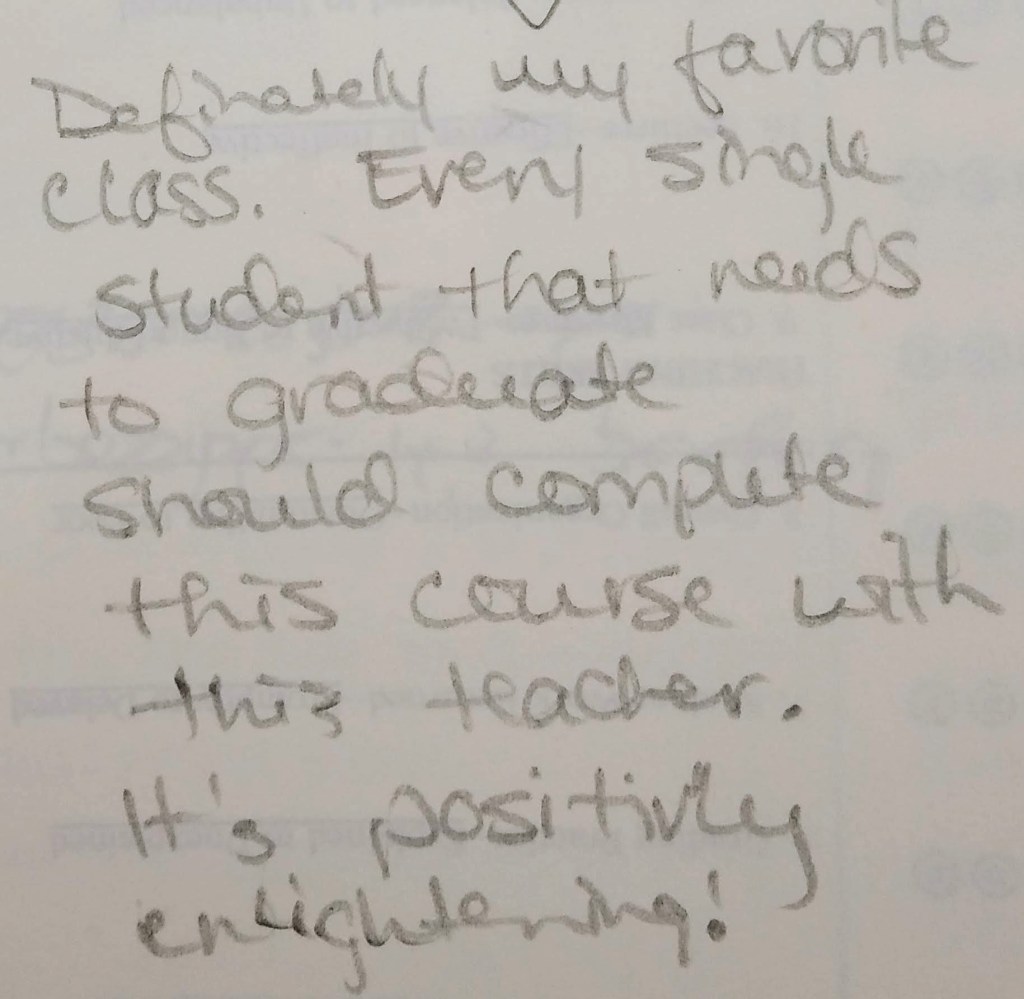

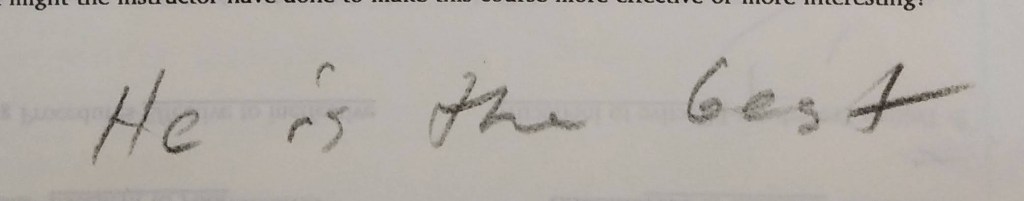

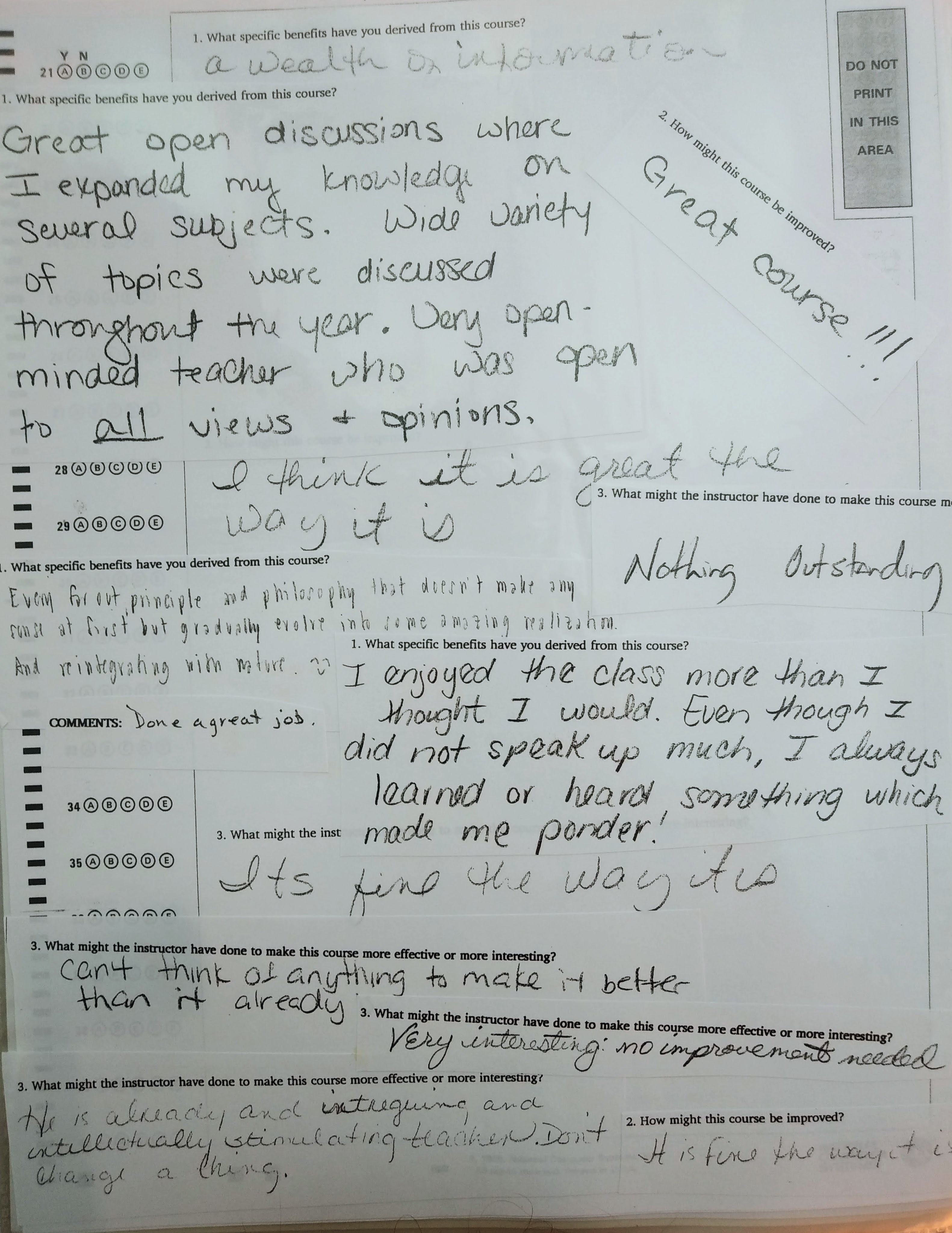

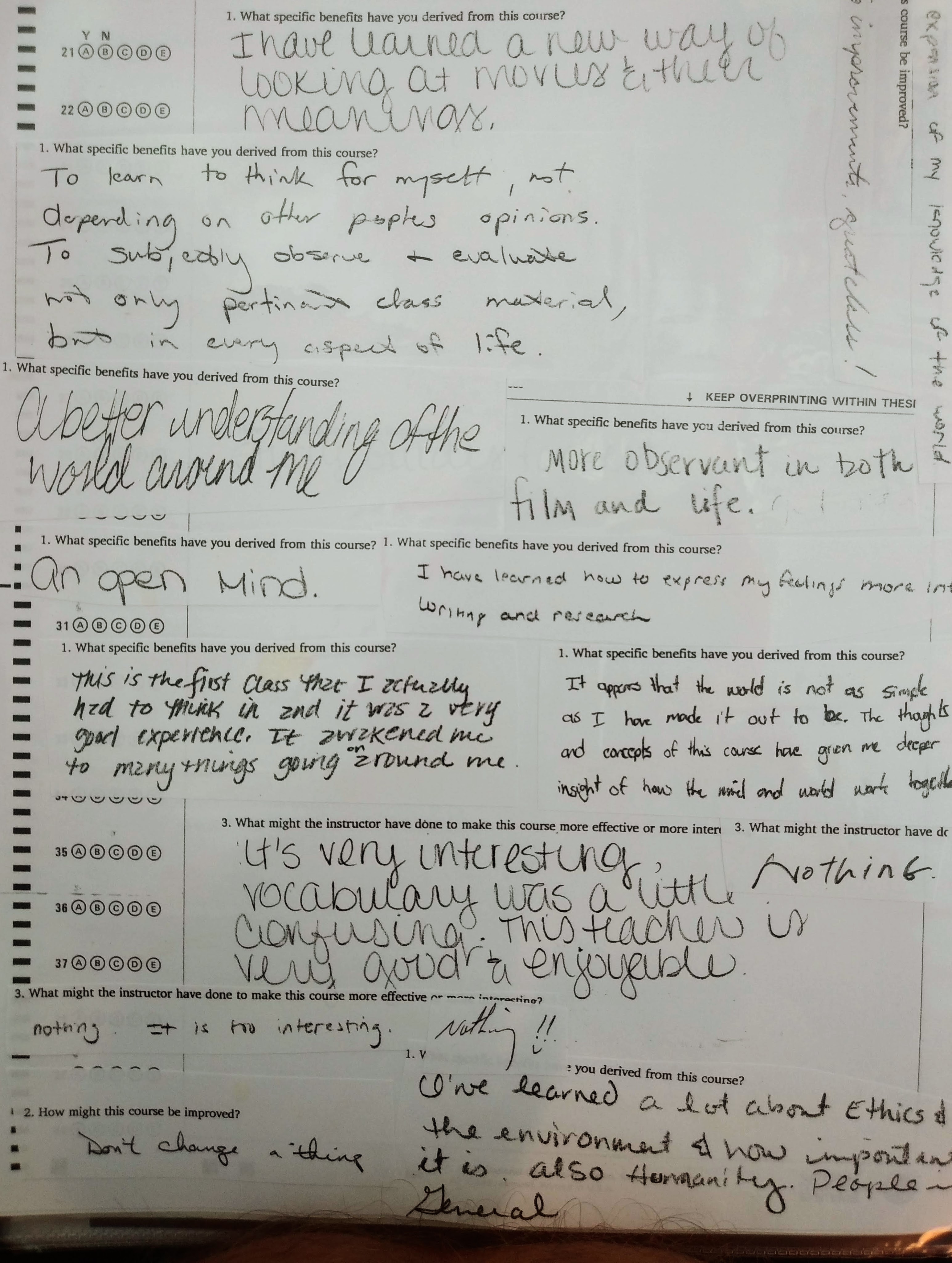

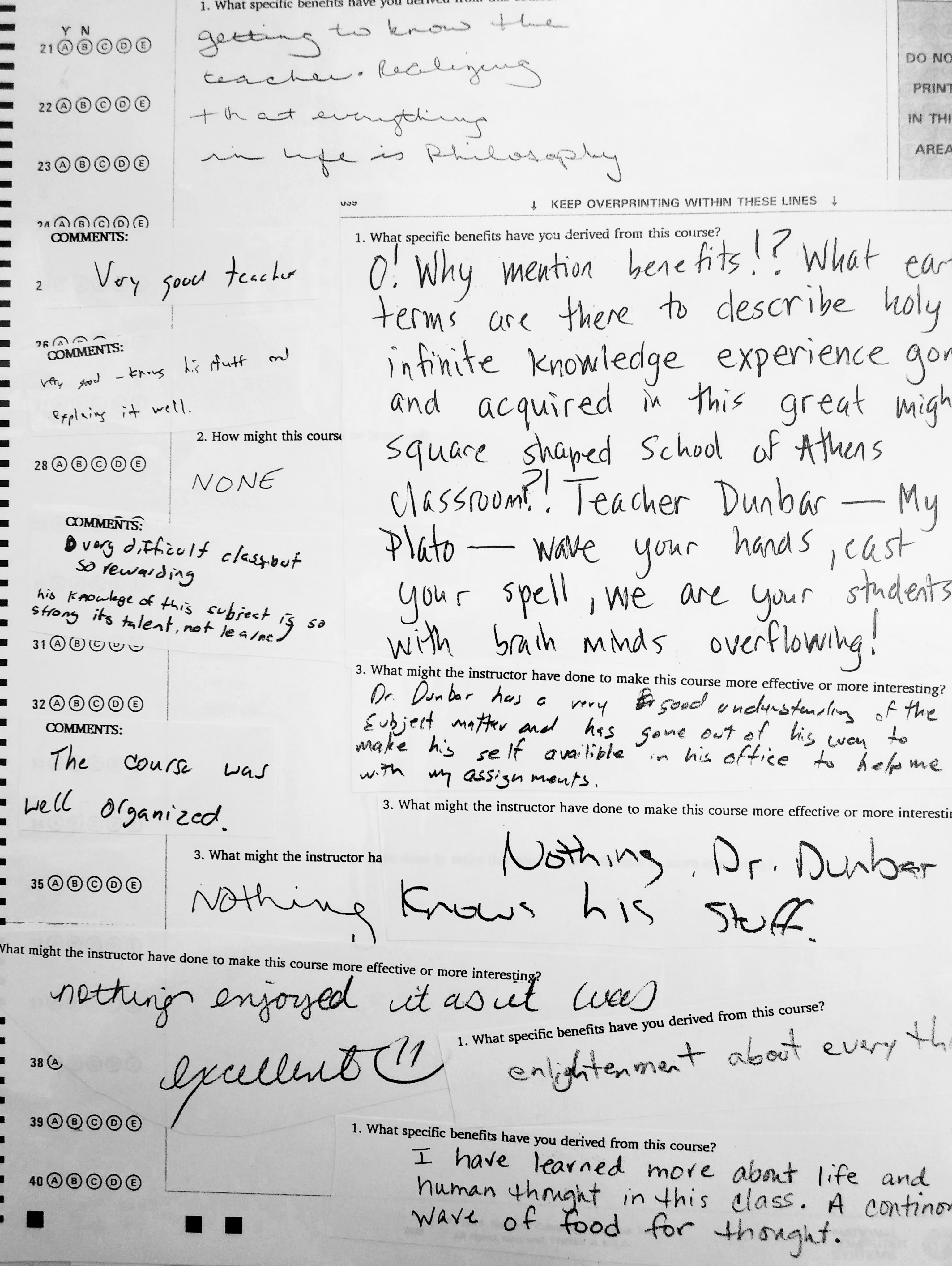

The other two parts of humanities were equally broad but just as much fun to teach. I also taught humanities at Unity College, where the entire history of world civilizations was packed into two parts, and at Northwest Florida State College, where it was all stuffed into one! Anyway, the film class became one of my favorites to teach. Over my career, I had over 90 sections of film, mostly at NWFSC but some at UWF as well as the ones at FSU. I taught over 100 sections of World Religions, and all kinds of other religion courses (see Syllabi below). Having retired in 2021, it’s fun reminiscing about all this. Students help. I recently received an email from a student, Blair, who I taught at FSU over 30 years ago. She was talking to her husband about me because I was the only professor she remembered and looked me up. She saw my articles and books on nature, balance, and spirituality and knew it was me. She thanked me, told me about her education, job, and two teenage sons, and congratulated me on my retirement. Needless to say, she made my day. The classes at FSU were huge, with well over 30 students. I did my best to make them discussion-based but it was difficult so I did quite a bit of lecturing, wrote key terms on the board, and asked specific questions while walking around the class trying to keep up with the material. For the most part, it apparently worked. With help from student evaluations, I won the Sarah Herndon Teaching Award presented annually to a graduate assistant. Here are a few comments from my first two classes:

See Appendix A for further FSU student comments.

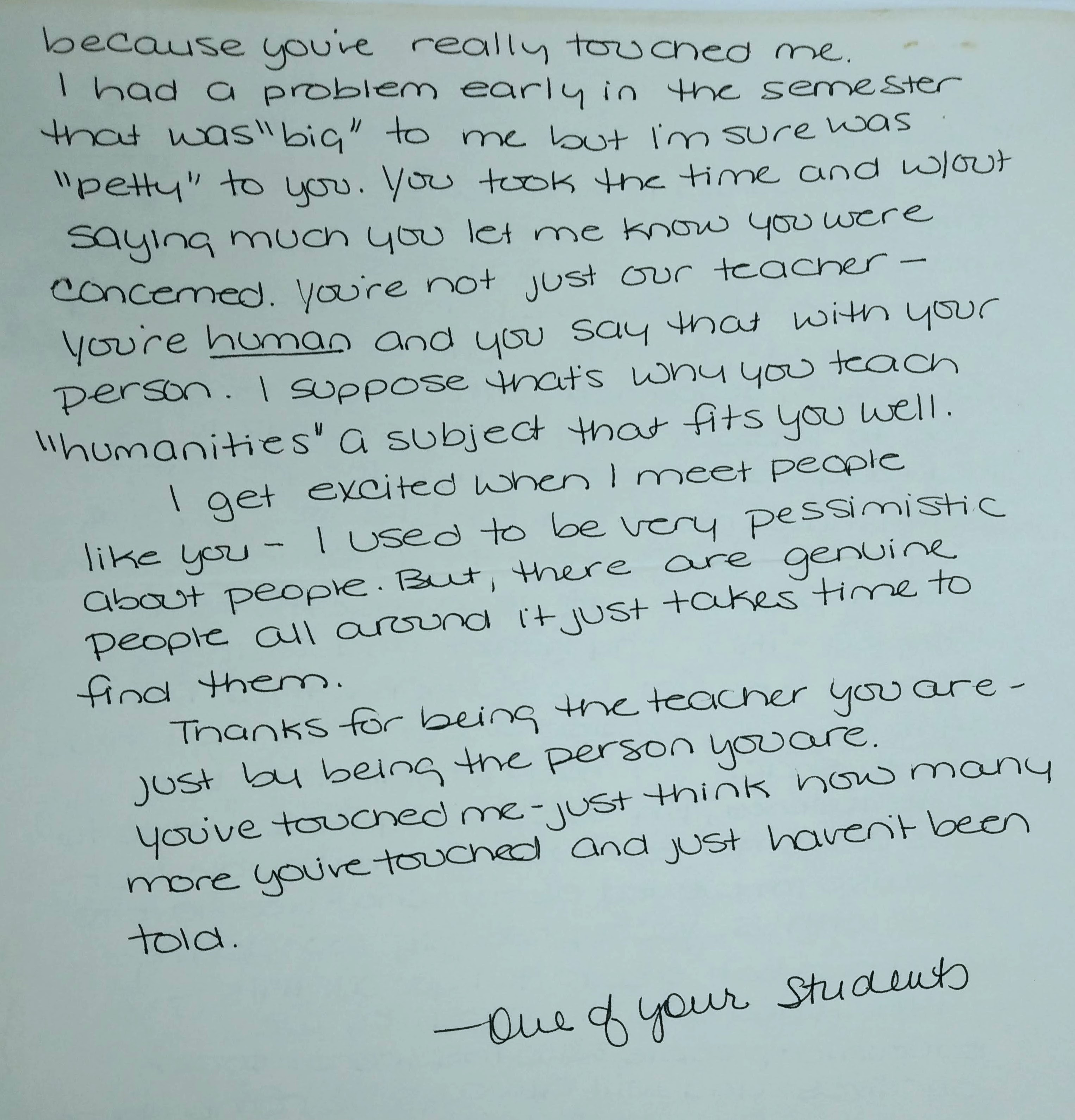

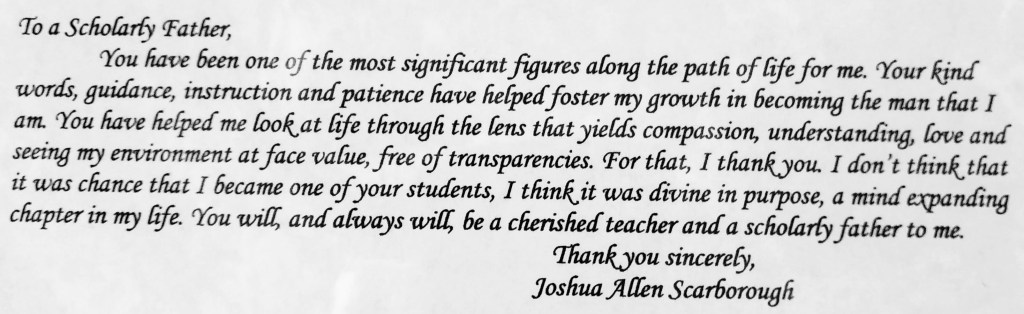

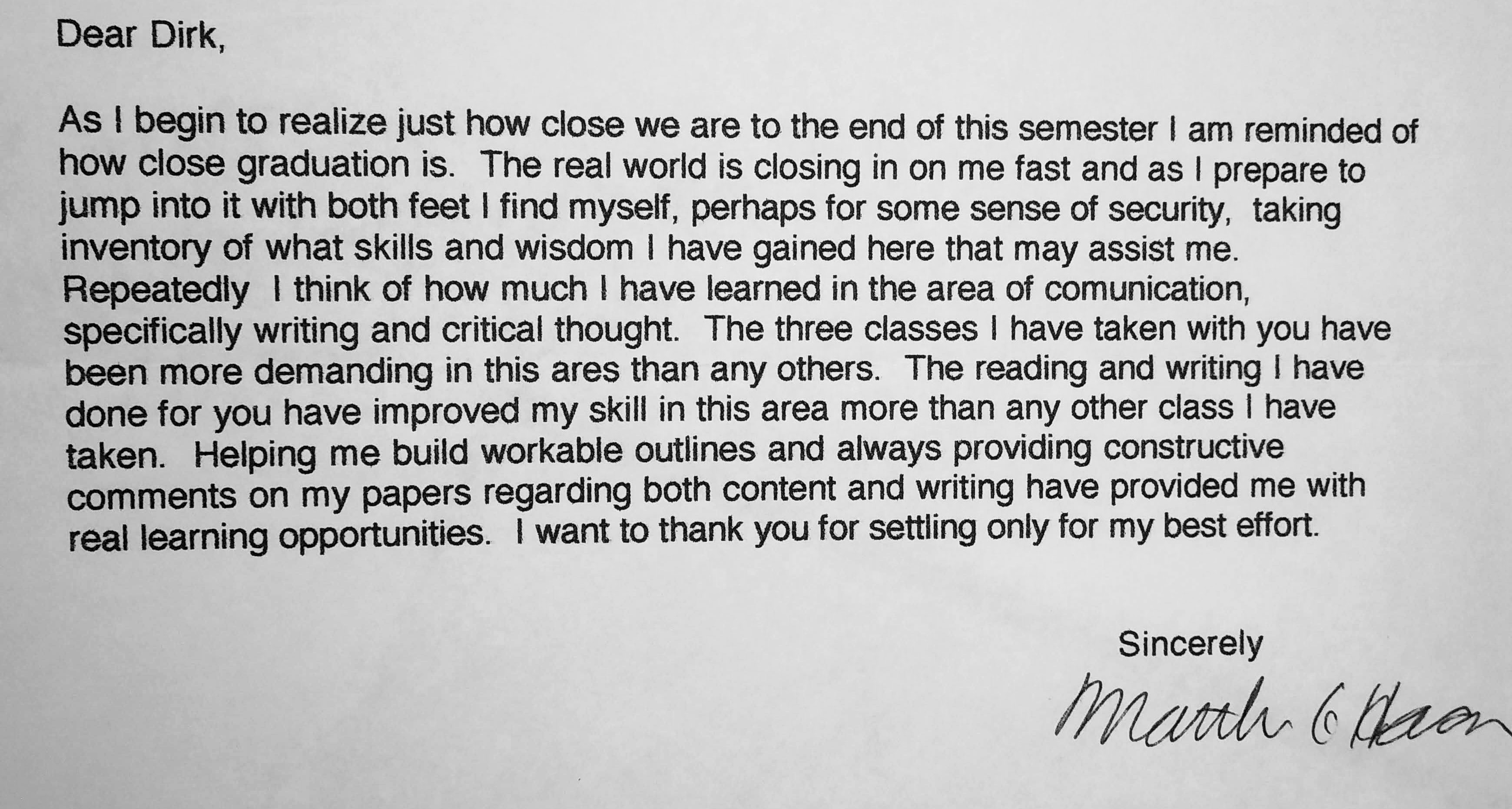

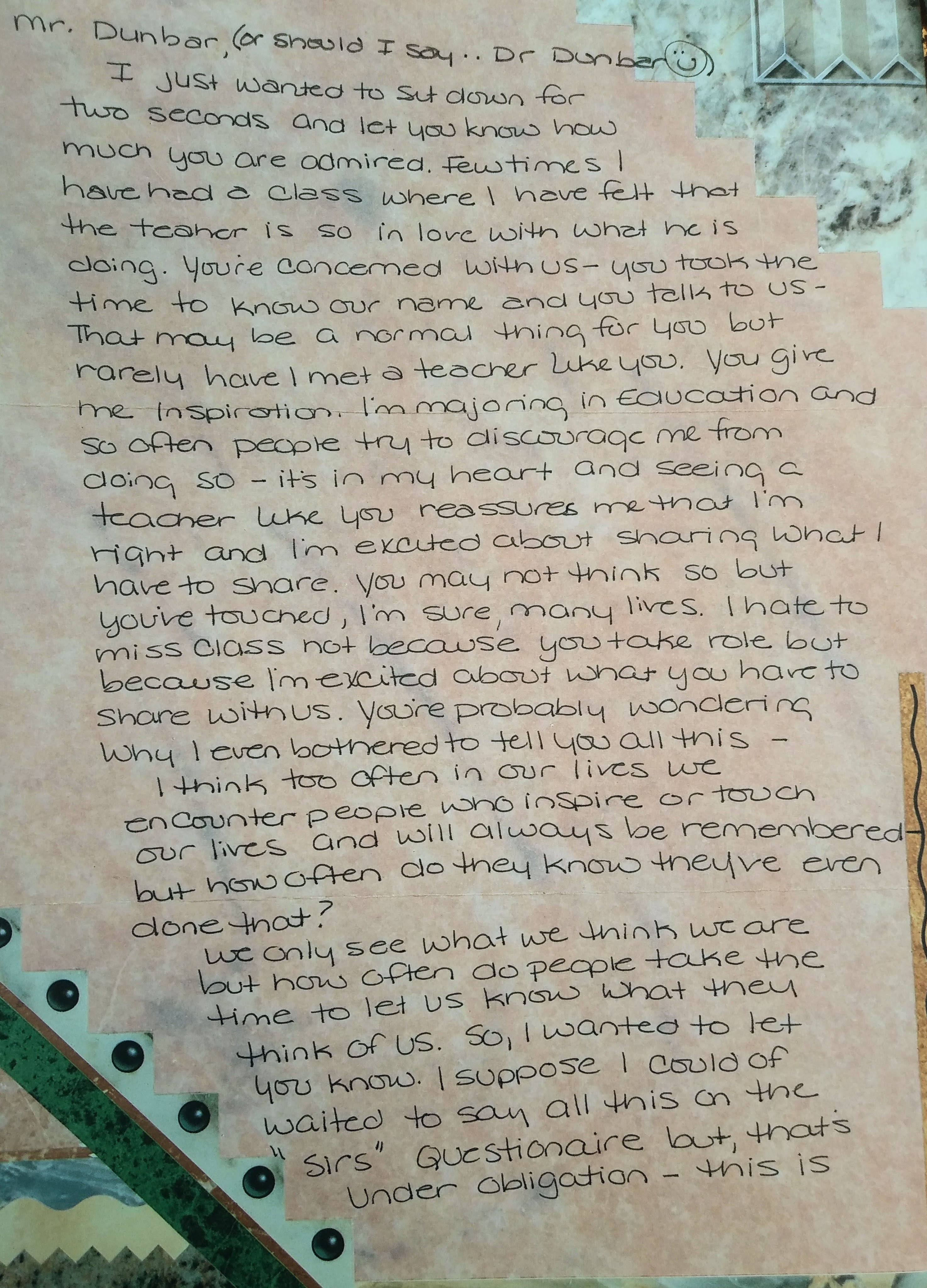

Here’s an anonymous FSU student letter I received at the end of my last semester there:

When you learn, teach. When you get, give.

Education is a process that goes on ’til death. The moment you see someone who knows she has found the one true way, and can call all others false, then you know you’re in the company of an ignoramus.

We must create a climate where people agree that human beings are more alike than unalike. The only way to do that is through education.

— Maya Angelou

As much as I enjoyed learning and teaching, the best part of every day was driving home, walking through the door, and greeting my family. Everyone knows how time flies, but nothing proves it more than kids. I saw Julia and Jeremy change daily, and then when you put weeks, months, and years into the equation, everything becomes clear. Parenting is a lot like teaching: you have to love and be everpresent, open, demanding, understanding, tolerant, and willing to compromise and change. Some of the most profound lessons you can have regarding teaching come from parenting.

In education, it is my experience that those lessons which we learn from teachers who are not just good, but who also show affection for the student, go deep into our minds.

Because the existing education system is oriented towards materialistic goals we need to pay special attention to inner values such as tolerance, forgiveness, love and compassion.

We can only transform humanity and create a happier more compassionate world through education.

― Dalai Lama

I applied for jobs at several colleges and universities and received more lucrative offers but decided on Unity College in Maine. Everything about the school called me. Besides being billed as “America’s environmental college,” the college–located on a beautiful rolling hill surrounded by woods and overlooking Lake Winnecook–had an awesome faculty, administration, staff, and a diverse student body. Everybody was on a first-name basis. I also found it synchronistic that the college emblem, the yin-yang symbol, was on everything from the stationary and buildings to the midcourt circle on the basketball court. Unity is a small town with a wonderful, spread-out community that my family loved. Our youngest daughter, Annabelle was born there and we quickly became a vibrant part of the local and college community. In short, it was a great decision and we cherished all four years there and still love the people we befriended.

The classes I inherited and taught in a two-year cycle include Aesthetics; Ethics; Humanities parts I and II; Great Issues in World Civilization; World Religions; Philosophy of Science; Philosophy of Religion; and Social and Political Philosophy. Except for humanities (which was required), my classes were initially small and composed of unique students who had at least one concern in common, the environment. I had six students in Philosophy of Science in my first semester, and none of them missed a single class! We read a survey text and the very difficult Order Out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature by Ilya Prigogine and Isabell Stengers (I switched to Roszak’s The Voice of the Earth the next time around) as well as Capra’s The Tao of Physics. We had lots of great discussions, the papers were fascinating, and I certainly learned a great deal. My passion for teaching and the environment helped quickly fill my classes. I could talk for hours about each class but suffice it to say it was a challenge and a joy. Along with the survey texts, I added a number of my favorite relevant books to various classes, such as Sam Keen’s The Passionate Life for Ethics, The Bhagavad Gita and Daode jing to go with the Iliad and Aeneid for Humanities Part 1, and The Shock of the New to Aesthetics.

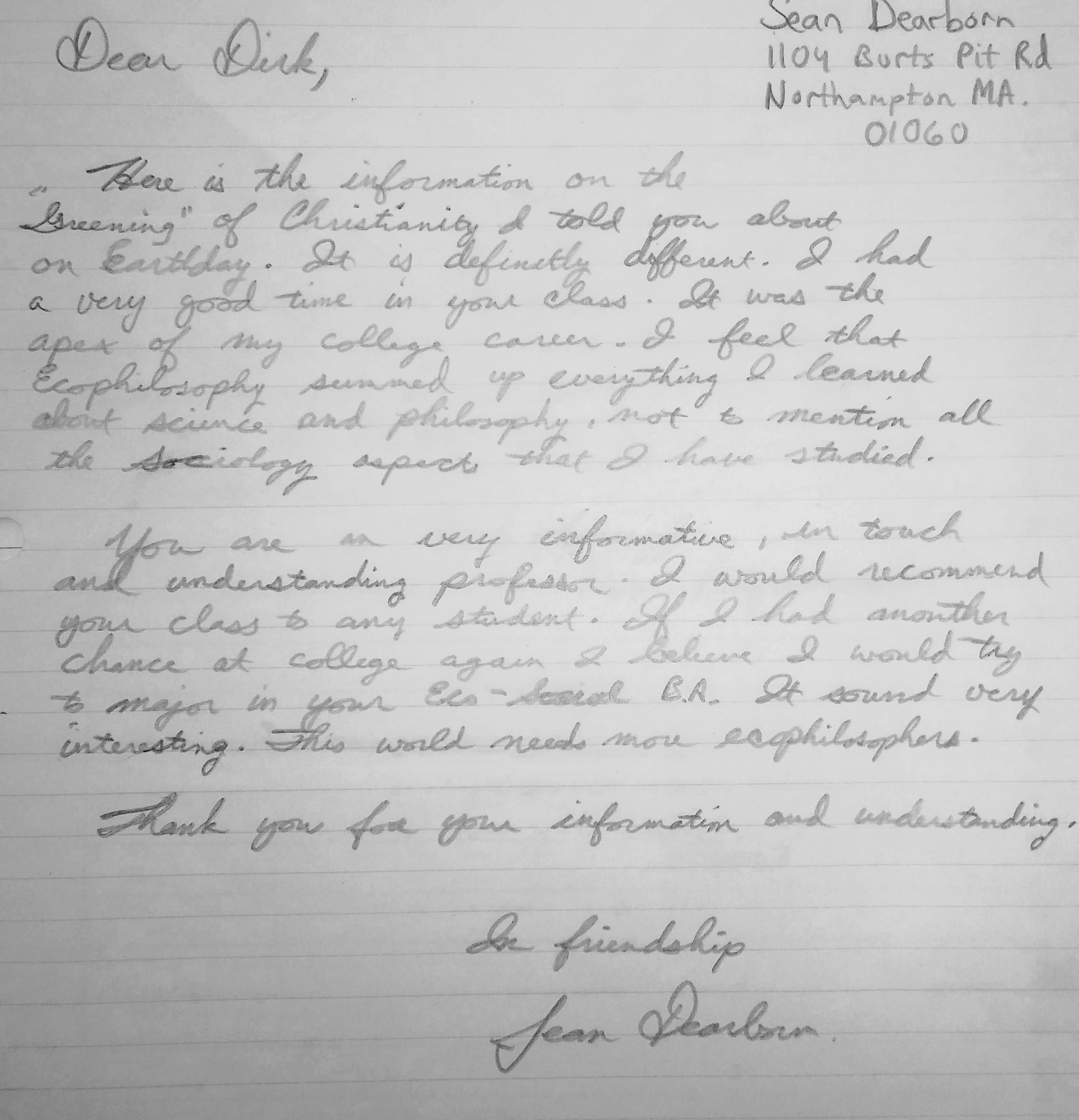

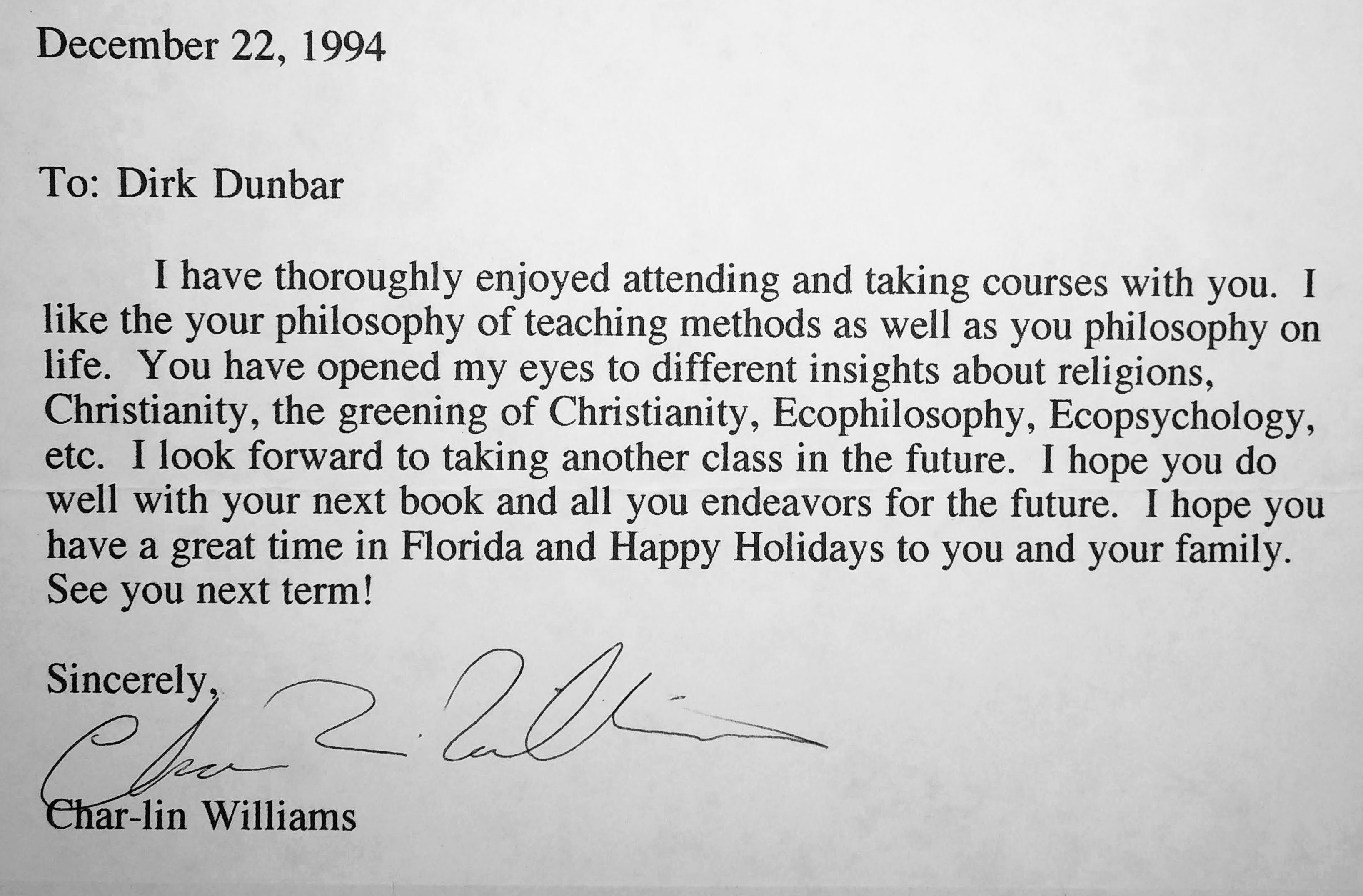

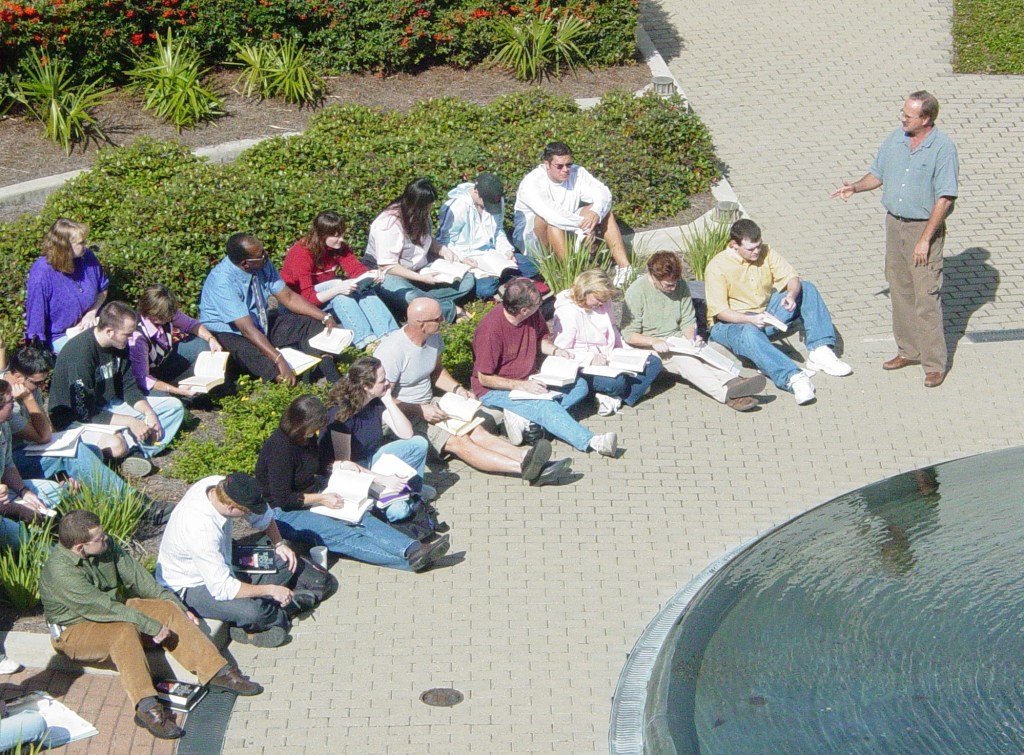

During my second and third years there, I added a few topics courses–Animal Rights (which I co-taught), Ecophilosophy, and The Meeting of East and West in Contemporary Culture–that were instant hits. The latter two became part of my teaching cycle. I really enjoyed the Ecophilosophy class and the discussions seemed to give a deeper purpose to students’ passion for nature, and they were not afraid to say so. Unfortunately, I do not have any extant syllabi but I remember we read Henryk Skolimowski’s Eco-Philosophy: Designing New Tactics for Living and a handbook I put together filled with essays from some of my favorite scholars. For the East meets West class we read Theodore Roszak’s The Making of a Counter Culture, Fritjof Capra’s The Turning Point, Ram Dass’s Be Here Now, Hermann Hesse’s Siddartha, Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums, and Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. There was definitely a hippie vibe at the college–shared many by students and faculty alike–and that class captured it. As with all my classes, I would change the environment. We would almost always sit in circles, go outside now and then (there were some great natural places to sit in a circle), or occasionally meet in the Student Center. Students would often lead various parts of the discussion on certain sections of the readings; I would have a couple of guest speakers; would occasionally show slides or documentaries; and, along with tests and papers, students wrote informal journals. I was always open to suggestions and willing to implement changes. Teaching is a two-way street.

I’m not a teacher: only a fellow traveler of whom you asked the way. I pointed ahead–ahead of myself as well as you. ― George Bernard Shaw

Do not train a child to learn by force or harshness; but direct them to it by what amuses their minds, so that you may be better able to discover with accuracy the peculiar bent of the genius of each. — Plato

It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy in creative expression and knowledge. –Albert Einstein

“You teach me, I forget. You show me, I remember. You involve me, I understand.” ― Edward O. Wilson

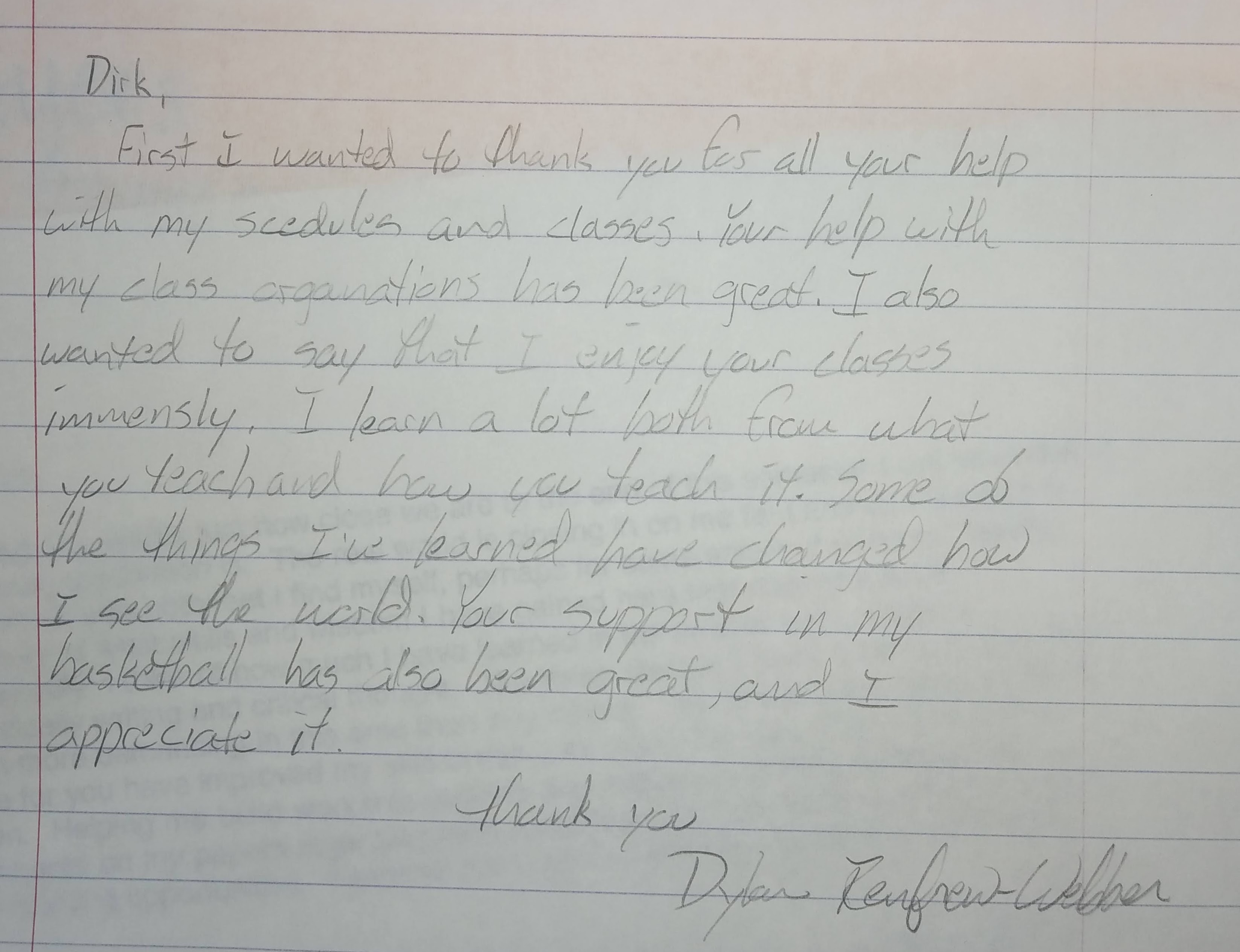

I was also highly involved with student life at Unity. I served as faculty advisor for the Philosophical Society, Recycling Club, and Woodsmen Team, as an assistant basketball coach, gave many talks at various events, organized panel discussions, and brought in many guest speakers from the Humanities Council and Sierra Club to environmental authors and the Green gubernatorial candidate and friend, Jonathan Carter. I was the college’s student-elect banquet speaker and was chosen to be the faculty advisor for the Northeast region’s Student Environmental Action Coalition (SEAC). We had some amazing SEAC conferences and celebrations, like the 1995 Earth Day that included delegates from a dozen colleges, speakers and panel discussions, music and activities, and stands, booths, and tents that offered everything from environmental rhetoric to beer and vegan food. I even wrote poems and articles for the student newspaper, The Northern Lights, and played in a faculty rock band! John Sullivan, the director of food services and performing arts, helped make every event a success. Merle Saunders, Bela Fleck, Widespread Panic, Rick Danko, and many other musicians graced our stages. John and Jayne are still two of our best friends, as are Gary and Nancy Zane. Gary was the basketball coach, my tennis partner, and the leader of the band, Gary and the Pacemakers. I could go on and on about so many people but suffice it to say we have never lived in a place with so many kindred spirits–many of whom I talk about in Confessions of a Basketball Junkie.

My administrative duties were extensive. Besides serving on faculty search and library and department review committees, the General Education Committee, as a consultant for the Council of Independent Colleges on Environmental Studies, I chaired the Vision 2001 committee, initiated and co-authored a highly successful B.A. program in Environmental Humanities, was the humanities department director. As Jim Horan, my friend and department chair stated in my evaluation: “I find DIrk’s contribution to Unity’s student life, cultural activities, and governance to be outstanding, one that could well serve as a model for other faculty.”

I went to several “professional development” conferences while at Unity. They were all eye-opening. The first one was the New England Philosophy Association’s conference. I was surprised and disappointed with all the “one-upmanship” during the question, answer, and discussion following the presentations. The highlight was the talk by Annette Baier on Care Ethics. Clearly impacted by Carol Gilligan, Baier argues that our notions of right and wrong are based on two different value systems, one based on the masculine idea of justice involving reward and punishment and the other based on the feminine sense of trust and caring. Because the history of Western philosophy and jurisprudence has been dominated by men, she feels–along with Gilligan and many other feminists–that the nurturing power of care and trust have been excluded from our value system as it relates to gender as well as legal, political, and social structures. Being the first one to comment and a longtime ecofeminist and fan of Gilligan’s and Nancy Chodorow’s work, I briefly let everyone know how much I enjoyed her talk and why.

Knowledge is a procedure of heaping up facts; wisdom lies in their simplification.

Education without morals is like a ship without a compass, merely wandering nowhere.

Intelligence plus character–that is the goal of true education.

— Martin Luther King, Jr.

Fulfilling a longtime dream, I attended Esalen Institute for a week the following year and had the great fortune of being in Michael Murphy’s and George Leonard’s Integral Transformative workshop. Along with the meditation, body-mind exercises, lectures, and discussion, I was lucky enough to share some great meals with Mike and George and a couple of wine-filled evenings—one of which included sitting next to Mike on beanbag chairs watching a slide show of the history of Esalen. Mike gave me free access to the Esalen files, which helped in my research for my essay, “Eranos, Esalen, and the Ecocentric Psyche” (published in The Trumpeter). The same year I attended the Gestalt Therapy Conference in Toronto, where the featured speaker Theodore Roszak gave a presentation on his book, The Voice of the Earth. He wrote an endorsement for my book, The Balance of Nature’s Polarities in New Paradigm Theory, and we had dinner together at the Hilton high rise where we were staying. A year later, when I presented at The Center for Theology and Natural Science’s conference in Berkeley, we met at one of his favorite “watering holes.” After two beers and avid conversation, he gave me directions to People’s Park.

A year after that, Ulli, the kids, and I went to a Holy Cross Theology and Ecology conference in Port Burwell, Canada, which featured a three-day dialogue between Ted and Thomas Berry. They took turns responding to each other’s talks during afternoon and evening sessions. The Center is on a spacious peninsula with huge oak trees, a gorgeous landscape, and a swimming pool that Ulli and the kids utilized regularly. The interaction between the 40-plus participants was intimate and intense. I had lunch with Ted and Tom every day and we brought Ted and his wife Betty back to their hotel more than once. I will never forget the afternoon under a giant oak when Tom blessed Annabelle. The following year I attended Common Boundary’s “Inner Ecology, Outer Ecology” in Virginia. Tom was there and it was a true joy to spend time with him again. He asked me how my family was, especially Annabelle, whom he called a “magical child.” Some of the high points were Gary Snyder’s poetry reading (I got the squinty-eyed guru to sign my copy of Turtle Island), Ralph Metzner’s “Greening of Psychology,” Matthew Fox’s “Coming of the Cosmic Christ,” and Charlene Spretnak’s “States of Grace.” I sat with Karen Warren, whose work on ecofeminism I used in classes, at a couple presentations. Charlene, Karen, Carol Adams (author of The Politics of Meat and editor of Ecofeminism and the Sacred), and I sat around a table and drank beers at the end of the conference and talked about—among other things—the evolution of the human species and if we are to survive, the inevitability of peace and veganism.

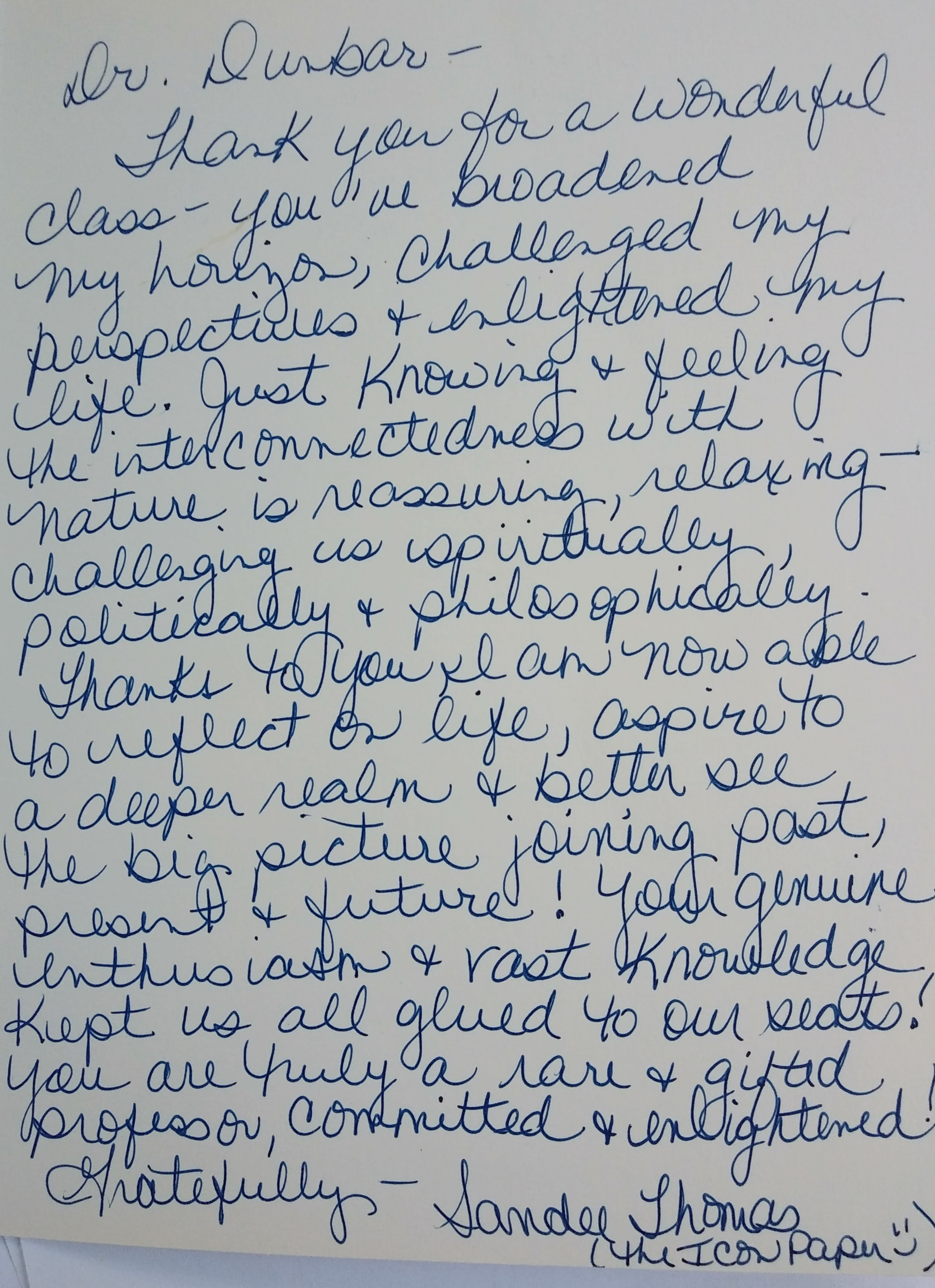

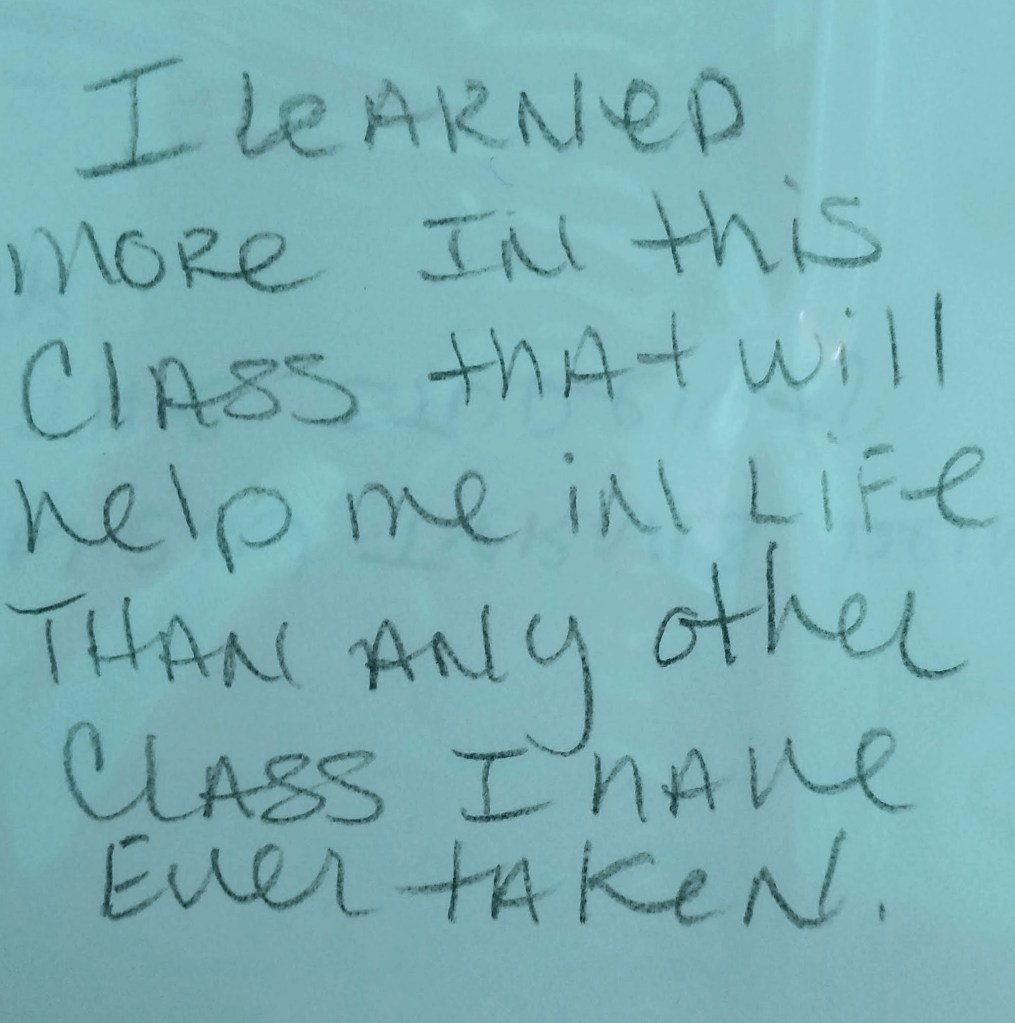

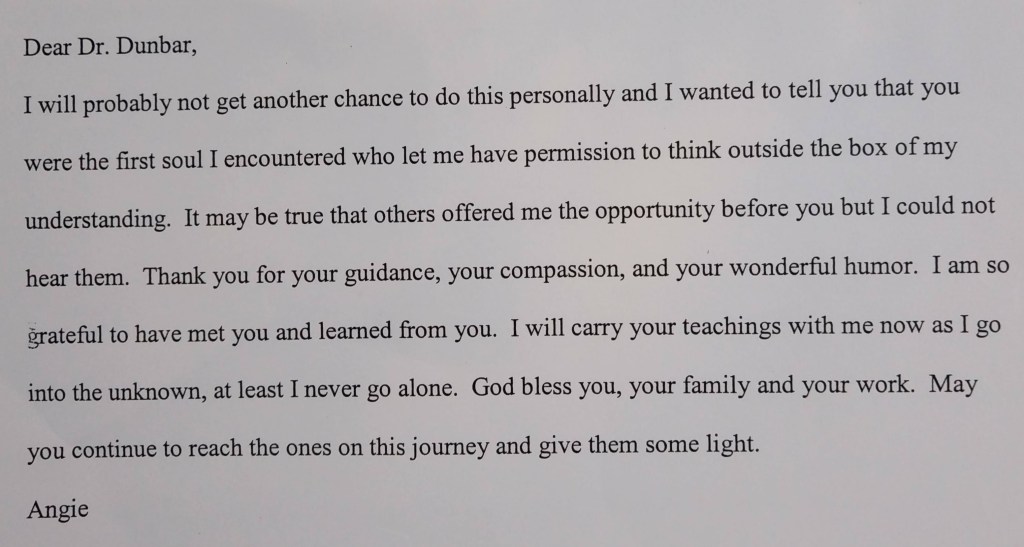

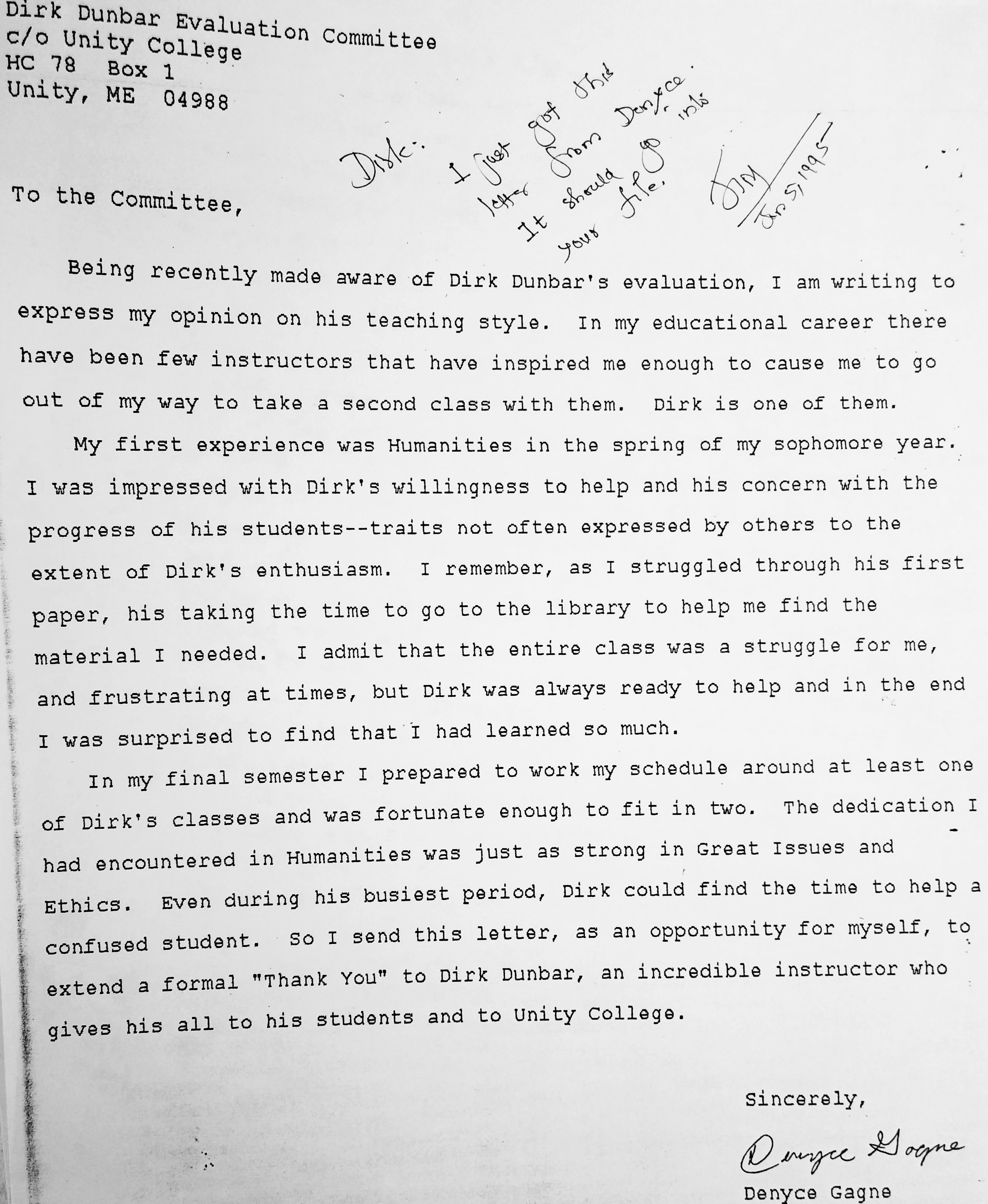

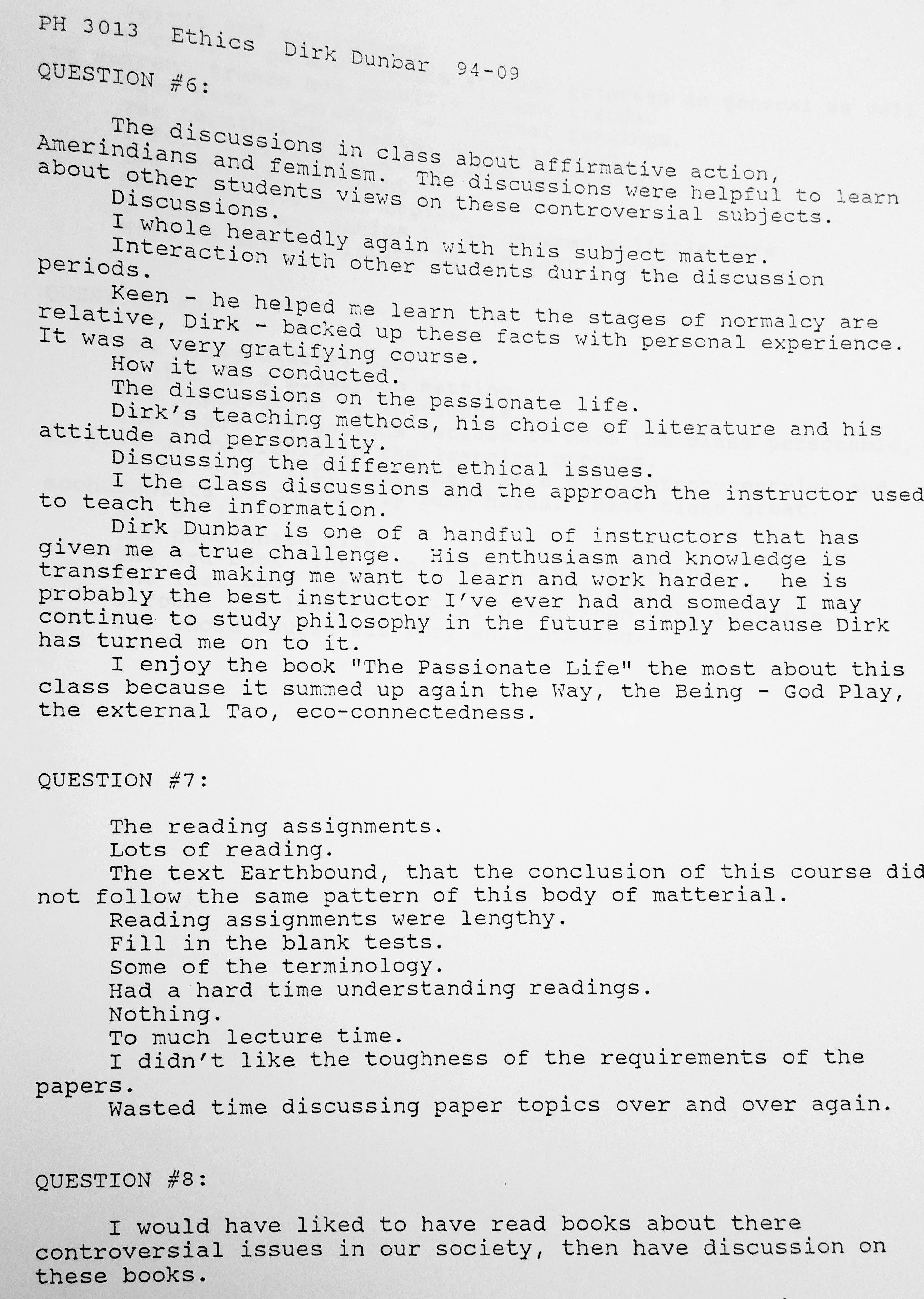

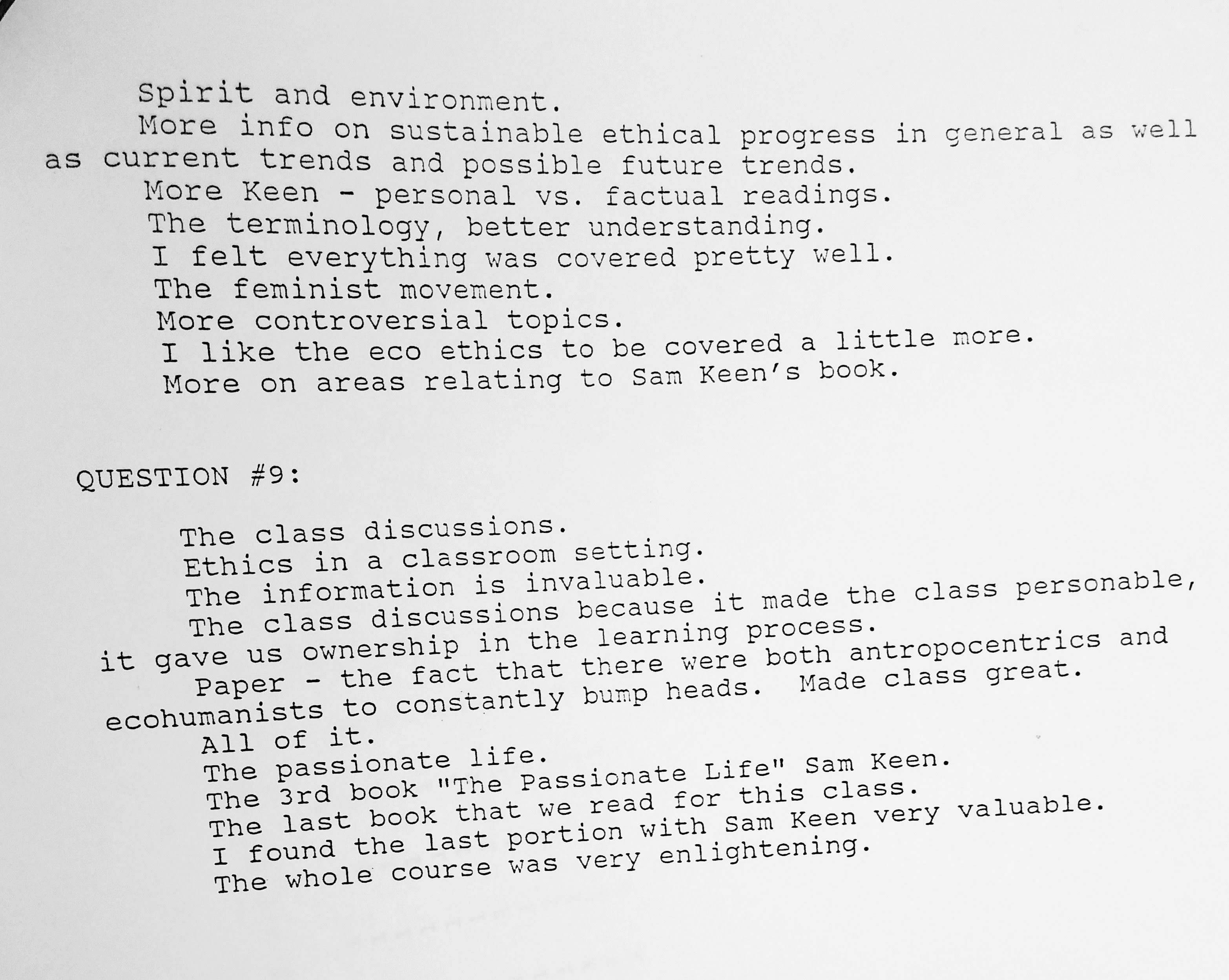

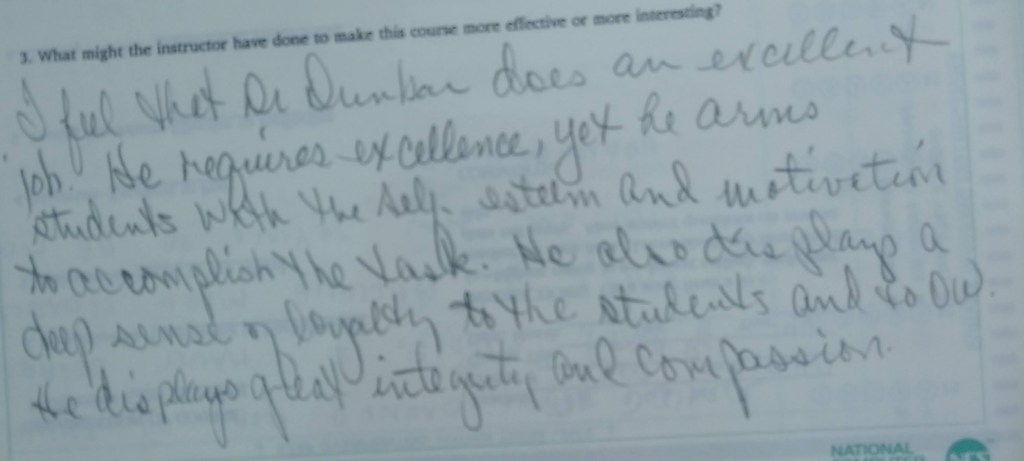

My passion for the place and people at Unity was reciprocated, as my chair, evaluating committee, and student evaluations indicate. As Jim Horan points out, 99.3% of my students at FSU and Unity strongly agree that I am an enthusiastic teacher and am recurrently regarded as “the best teacher I have ever had,” while other comments include “very enlightening,” “one of a handful of instructors that has given me a true challenge… making me want to learn and work harder,” and “This course allowed me to look inside myself and solidify some of my values along with redirecting some others.” Jim adds, “These reactions are also reflected in letters from former students in DIrk’s dossier that indicate that the writers gained lasting value from Dirk’s courses… it is this excitement described above that opens new doors and even new worlds to some students.” Also, “He has developed a following in the student body… and, as a result, Unity College is benefiting from an increased interest among students in philosophy and humanities…”

My evaluation committee recommended that I receive an early promotion from assistant to associate professor because “in all the principal areas of evaluation, namely, teaching, advising, scholarly development, and service, Dr. Dirk Dunbar has excelled.” Furthermore, “It is not a very common occurrence for a faculty member to become absorbed by the mission and vision of the college, make himself important to academic governance, and provide cement and links in the general college programs. This, Dirk has done. His energy and enthusiasm often keep him moving ahead of an otherwise lethargic system. He has made himself an invaluable member of the college community. We conclude that Dirk has made excellent and valuable contributions to the College community Dirk’s leadership abilities have been well documented in the letters of attestation he has received. His performance exceeds the promotion standard of ‘successful.'”

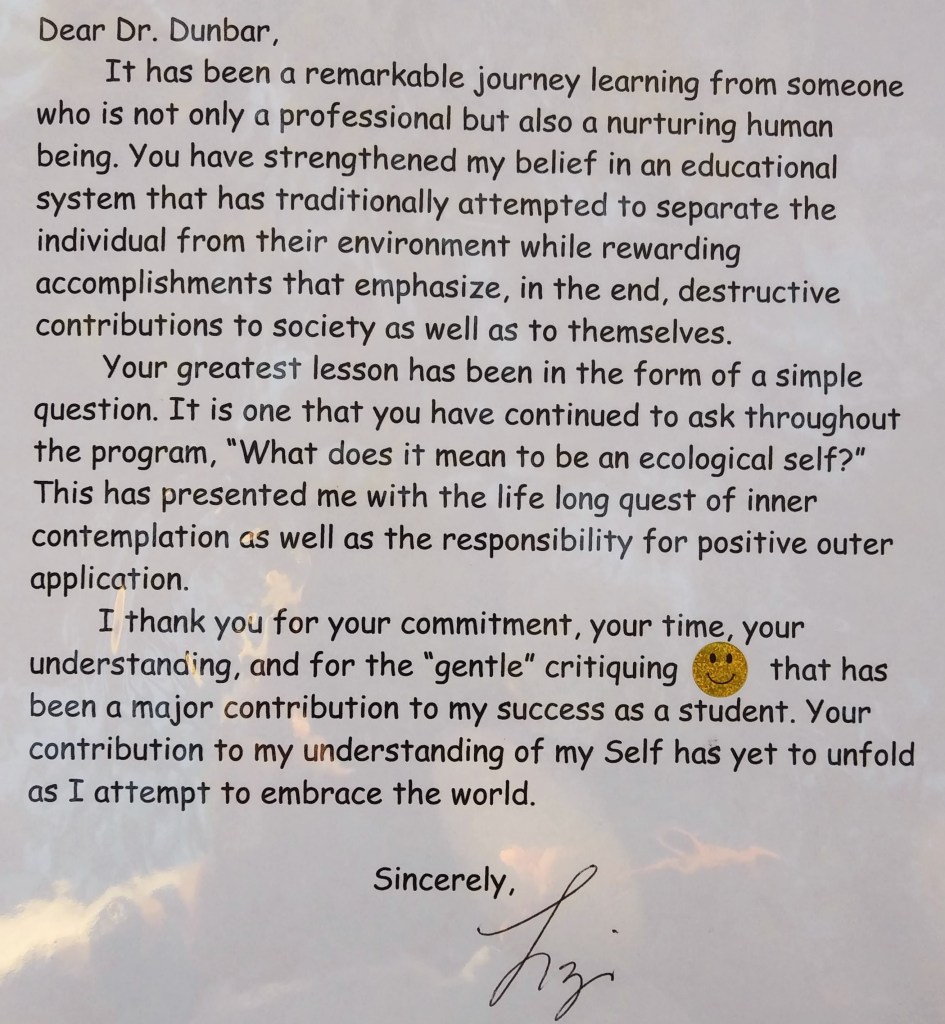

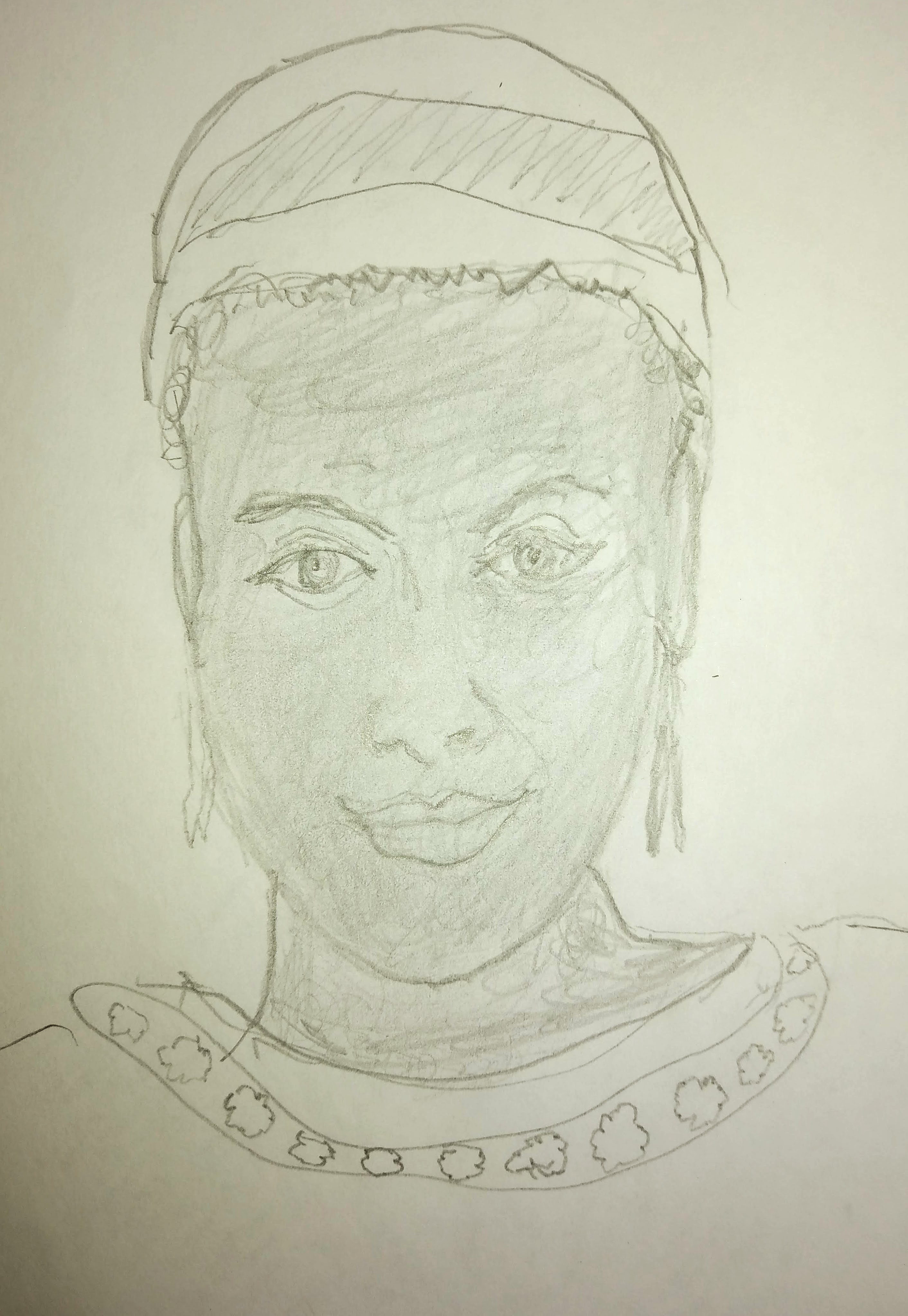

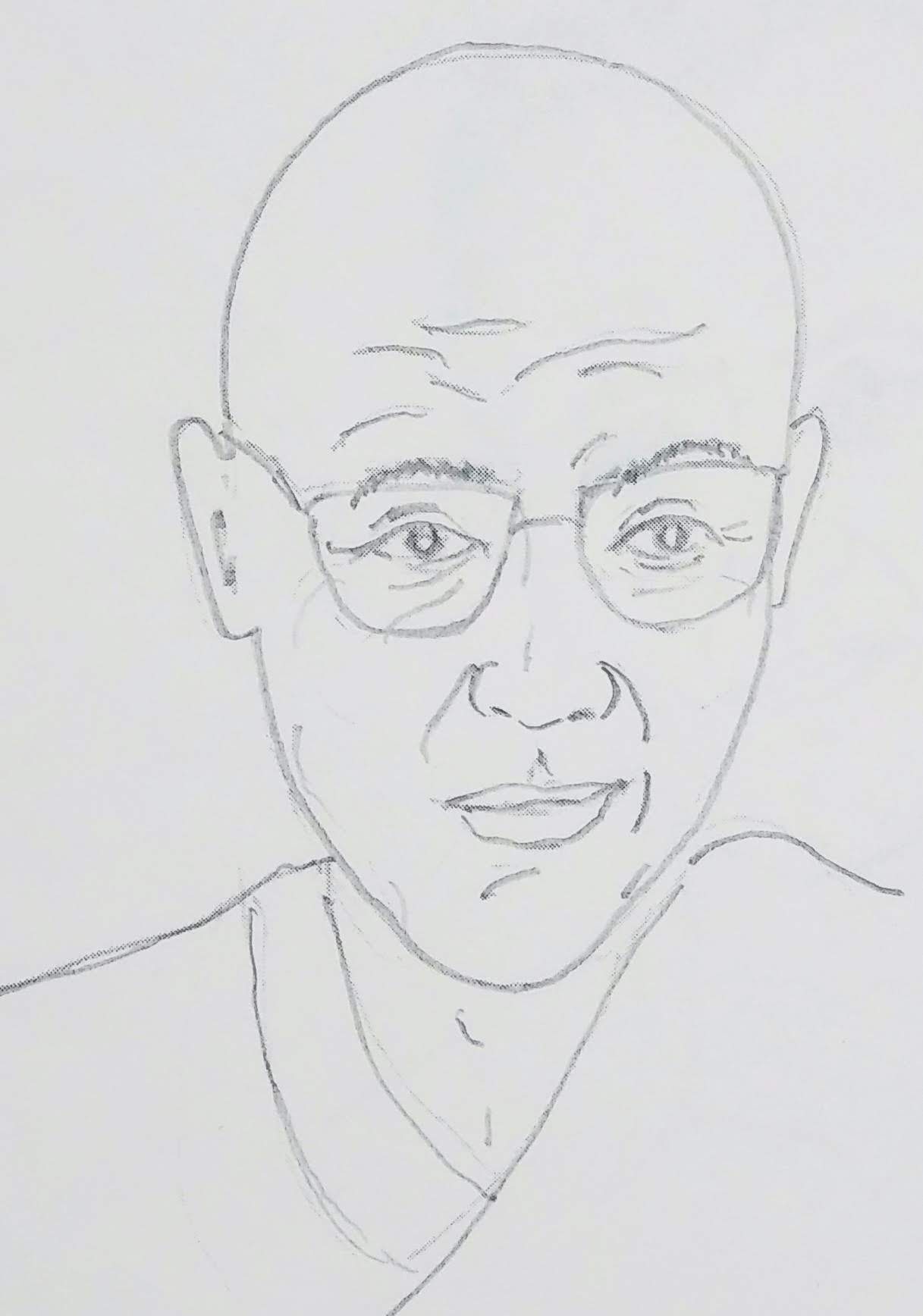

Here is a letter a student wrote to my evaluation committee:

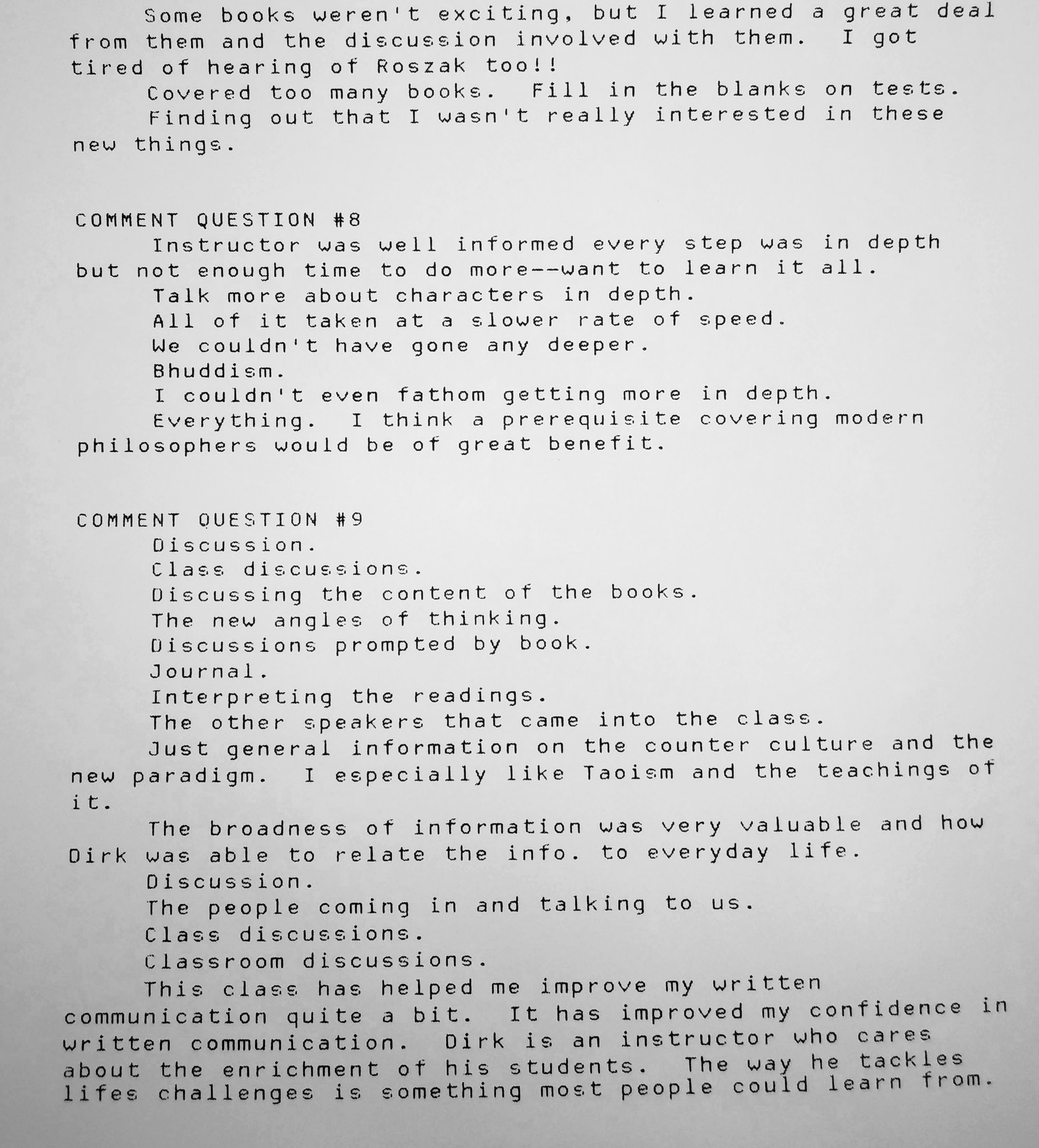

My student evaluations at Unity were exemplary. However, my enthusiasm can, as Jim Horan explains, rub some students the wrong way. Five out of 207 students during my first two years at Unity ranked my teaching performance as below average (83% regarded me as outstanding), while two of them called me “preachy” and “arrogant” and I understand why. I admittedly share my opinions, which along with my enthusiasm, can be offensive. So can my level of student expectations and grading practices. I readily admit in my self-evaluations that I am a difficult grader. I use grades, for better and for worse, to motivate students, to encourage them to be fully engaged, and to produce their best possible work. Despite my levels of enthusiasm and difficulty, I am almost always regarded as helpful, knowledgeable, accessible, and fair. Here are a few student comments on my evaluations (questions 1 to 5 and 10 to 18 are numerical answers):

See Appendix B for more Unity College student comments.

In sum, our time in Unity was incredible. We still make it back. In fact, I would have spent the rest of my teaching career at Unity if it were not for one thing–the weather. The winters were long and we were ready, especially Ulli, to get back in the sun. Since we love the Florida panhandle, I took a job in Niceville at Okaloosa-Walton Community College, which became Northwest Florida State College. I taught there for 25 years and retired in 2021. Unfortunately, I no longer have access to the syllabi I created for my classes at Florida State or Unity College but here are most of the ones from Northwest Florida State College: Introduction to Ethics; Introduction to Comparative World Religions; Cinema Appreciation; Introduction to Humanities; Introduction to Philosophy (philosophy flyer). Along with those courses I taught two that were created by winning grants from The Center of Theology and Natural Sciences in Berkeley. The first one was Issues in Science and Religion (Issues in Science and Religion) which I co-authored and co-taught with my colleague, Jon Bryan. The other was Science, Religion, and Nature (Science, Religion, and Nature) which I authored, presented at a conference in Berkeley, and taught for NWFSC as well as UWF.

Community college was a different world for me. We were required to teach 5 courses a semester with 25 to 30 students in each class. It took a while to get used to all the class time and grading required. It was also a different student body than Unity in terms of being more politically and religiously conservative, more formal, and more diverse. Unlike in Unity, the students at OWCC/NWFSC did not share the same kind of environmental background or interests. Still, I loved it because most students were open-minded and eager to learn. Though I enjoyed teaching all of my classes, my favorites were film and world religions, probably because it was easy to provoke class discussions. Also, those classes allowed me to address many issues that are close to my heart and that students seem to be most open to in terms of reconsidering their own perspectives, seeing the value of diverse worldviews, and recognizing the power of tolerance. Many or most of the students were raised in Christian homes and were unfamiliar with other religions, and many had been taught that those religions were not just false, but also obstacles to salvation. After learning about the actual teachings and cultures involved in multifarious religions, and discussing them with colleagues, the majority of students developed an appreciation as well as a deeper understanding of various ways to view and revere ultimate reality as well as the value of tolerance and potential for ecumenical perspectives. The world of film offers similar opportunities.

One of the themes that run through many of the movies I show is based on the transformation of the Hollywood hero from a masculine good-over-evil conquerer into a self-realized, centroverted archetype who experiences a victory over the ego. The vision of such heroes, shared by ever more filmmakers, depicts humans at home in the cosmos, deconstructs the masks we have put on our enemies, and espouses the spiritual in the natural. Here are just a few of literally hundreds of examples: the ecopsychology of Instinct and Phenomenon, the ego-to-eco transformations in Seven Years in Tibet and A Civil Action, the ecofeminist sensibilities of Contact and Thelma and Louise, the Afrocentricity of The Color Purple and Do the Right Thing, the Eastern philosophy of Gandhi and The Matrix, the aboriginal Earth wisdom in Pocahontas and Dances with Wolves, the creation spirituality in The Fountain and Tree of Life, and the Green politics in Bulworth and Avatar all point to common goals. The first is to “wake the world” to the sacred feminine and the second is to create a hero whose victory equals the death and rebirth of ego-consciousness in a journey intended to supplant aggression, revenge, and material gain with self-discovery, equanimity, and planetary identity.

The job of an educator is to teach students to see vitality in themselves.

Life is not a problem to be solved but a mystery to be lived. Follow the path that is no path, follow your bliss.

What we’re learning in our schools is not the wisdom of life. We’re learning technologies, we’re getting information. There’s a curious reluctance on the part of faculties to indicate the life values of their subjects. — Joseph Campbell

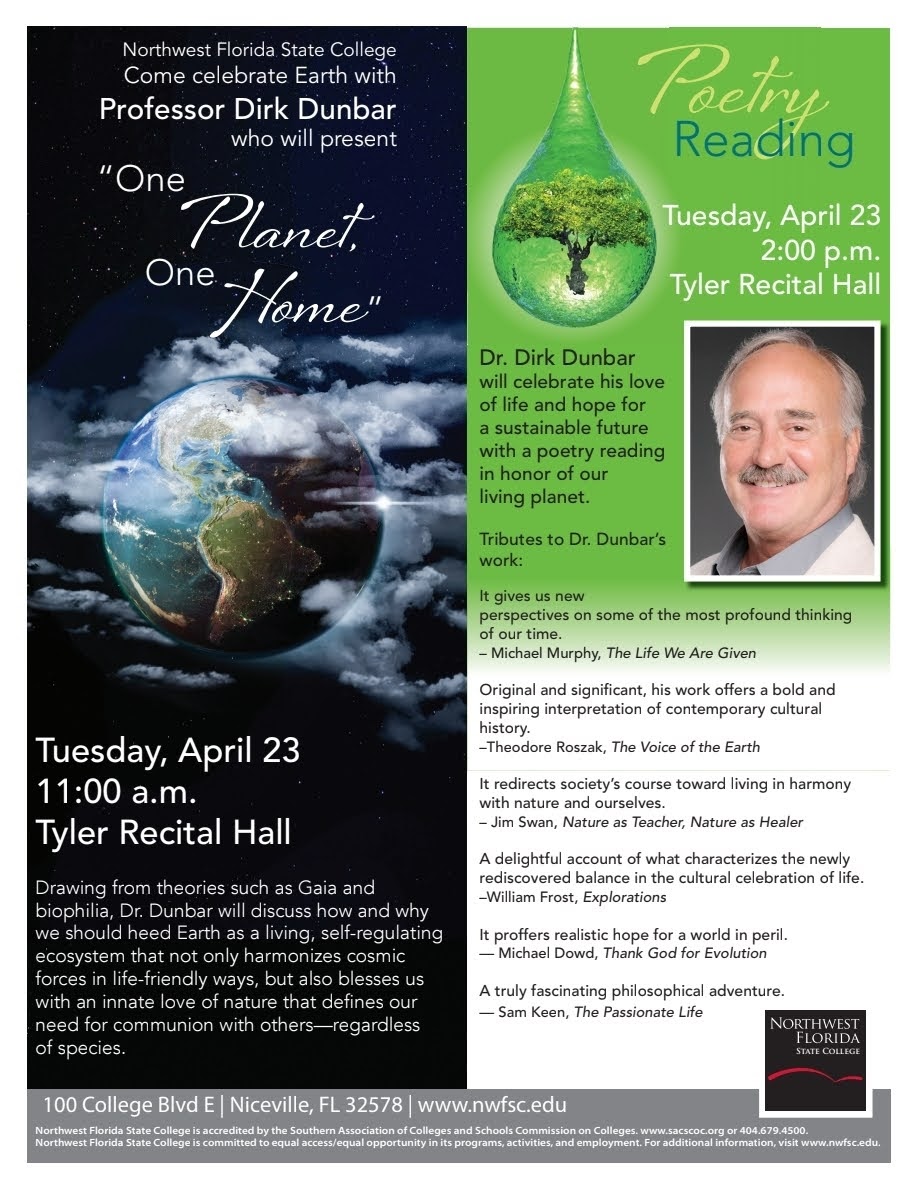

I was very active with student life outside of the classroom. For instance, I revitalized the Environmental Club, served as an advisor for many years, and initiated the college’s recycling program. I gave dozens of environmental talks at the college, hosted panel discussions, and brought in speakers (including ecofeminists, deep ecologists, and environmental scientists). I instigated twenty straight Earth Day celebrations that included planting trees and shrubbery, talks and panel discussions, and/or live music and food and drink. Besides the college, I have given multiple presentations Unitarian Universalist Church, the Niceville Library, and many other venues. I was involved with college athletics, spoke to basketball teams, and volunteered as a tutor. I attended most of the student plays, dance facets, art exhibits, and other productions; went to hundreds of home sporting events; and shared my work with faculty art exhibits. Other co-curricular endeavors included hosting Tibetan Buddhist monks on two occasions, bringing them to classes and the beach, and sharing various daily activities. It was a wonderful experience to befriend such enlightened people–first Sonam and Thupten then Jamba and Yeshi.

My curricular endeavors at the college were many. Besides being one of the first professors to offer online classes (which was at the time especially beneficial to military personnel), I served on a lot of committees, including ones involved with the Collegiate High School, Staff and Program Development, Student Co-curricular, Interdisciplinary Studies, AA to BA Curriculum, College-Wide Council, Staff and Program Development, Recruitment and Retention, Advising, Charter School Seminar Planning, and Marketing and Recruiting. I also served as a Consultant and Co-author for the Council of Independent Colleges’ Program of Environmental Studies and Teacher Preparation. Besides chairing the Student Activities Committee for six years, I helped develop the AA to BA Interdisciplinary Humanities Program and authored the Environmental Studies major for the program.

Taking advantage of faculty development funds, I attended some great conferences and workshops. Besides the Center for Theology and Natural Sciences Conference, I attended two Esalen Institute workshops, one on Yoga and Meditation and the other on “The Life We Are Given” (the title of Michael Murphy’s and George Leonard’s book). I also went to an Eranos Conference in Ascona, Switzerland. The so-called “Pearl of Lake Maggiore,” Ascona rests on the north side of the lake and spreads up Mount Verita—the Mountain of Truth. Besides being a countercultural Mecca, it is the birthplace of the Eranos proceedings that began in 1933 and included Carl Jung, Erich Neumann, Joseph Campbell, Daisetz Suzuki, Mircea Eliade, and other scholars who married mind and matter, spirit and nature, and East and West. Under Jung’s guidance, Eranos participants adopted coincidentia oppositorum (a coincidence of opposites) as their motto. Clear progenitors of the three paradigms, the scholars synthesized aboriginal Earth wisdom, Eastern thought, and Mother Earth archetypes to present potentially healing myths and create prescriptions for the “unbalanced” Western psyche. While researching for my Ph.D. dissertation, I stumbled across the Eranos Yearbooks and was hooked. On the first night of the conference, Tilo Schabert, the program director, invited Ulli and me to join a small group of presenters at an Italian restaurant high above Ascona, where we sat on outside benches and shared some great food and discussion. A professor at Erlangen and author, Tilo shared stories of the old Eranos meetings that floored me. The conference was captivating, as was ambling through Ascona, visiting museums, gathering stones from Mount Verita, and strolling the sacred grounds once owned by Olga Froebe-Kapteyn, who hosted the original meetings on the shoreline of Lago Maggiore.

An understanding heart is everything in a teacher, and cannot be esteemed highly enough. One looks back with appreciation to the brilliant teachers, but with gratitude to those who touched our human feelings. The curriculum is so much necessary raw material, but warmth is the vital element for the growing plant and for the soul of the child. — Carl Jung

What has meant the most to us about NWFSC and the Niceville community is all the kindred spirits. I just had lunch with my friends and colleagues–Charlie, Dean, and David–and though I hadn’t seen them since I retired, we picked up right where we left off. I won’t even try to name other close friends because there are too many. Suffice it to say that I have been blessed with wonderful students and colleagues. I had former students constantly stop by my office to thank me and also received an abundance of letters, cards, books, icons, pictures, and other gifts that students have given me. The following comments on my evaluations attest to the reciprocal relationship I had with my students:

Here are some comments copied and pasted from the college website from my last semester at NWFSC:

- He is the best teacher I’ve ever had. Down to earth and knowledgeable on everything related to humanities. Honestly, this guy is too good to just be teaching here. He understands the movies shown and the meanings behind all of them. He relays information smoothly and with actual care for the topic. He’s awesome.

- Dr. Dunbar is now one of my favorite teachers and I will certainly recommend him to anyone who asks for a good class or teacher to take.

- Dr. Dunbar is a great teacher, really spends time with the students and makes sure they understand the information.

- Amazing teacher, always there to help and understand about family issues and medical issues. He’s impacted my life and college completely and I’m glad to have had Mr. Dunbar as my instructor.

- He is very amazing, as a teacher and person. Extremely enthusiastic and willing to help anyone who needs it. I would take more classes if teachers were like him!!! Definitely teacher of the year!!

- He is so so enthusiastic about the material and incredibly smart. I really enjoyed having him and I am taking him in the future. Incredible professor.

- His demeanor makes the class one you won’t want to miss. His passion for his teaching is inspiring.

- Dr. Dunbar was an amazing professor! He is very enthusiastic about this subject matter, and he helps pass that enthusiasm on to his students. He did particularly well with his explanations of the messages and techniques in the films. He also did an amazing job with helping us students to be able to analyze the films ourselves.

- This course was amazing. I learned so much from Dr. Dunbar. I got to explore a world of cinema that I did not even know about. I have nothing to say about improvements. I found nothing wrong with this course. One of the coolest teachers I have ever had.

- This course was wonderful. Growing up in a very strict Christian household, I had very little knowledge of other religions coming into this class. I learned so much about other religions and enjoyed it. It helped me get a better understanding for other people and their religious beliefs.

- The course has broadened my perspective and knowledge of the different religions that we have in our world today. Learning these religions in an environment where nothing was pushed for you to enjoy or believe in was amazing.

- I took Introduction to World Religions as a required Humanities general education credit; I do not at all regret choosing this class. Skeptical at first, I really grew to enjoy Dr. Dunbar’s teaching style. I definitely grabbed the Gen Ed credit I needed, but more than that, this class broadened my worldview considerably. The only way this class could have improved would have been if the students were more participatory; Dr. Dunbar frequently reached out for student input and discussion, but the class was too timid to chime in.

- Dr. Dunbar is very enthusiastic about what he’s teaching, and that helps make the class fun and easier to learn in. He knows most of the information off the top of his head, and that is truly a gift when you are teaching, because when you know what you’re teaching someone else and are excited about it-that is when the students will learn the most. The only way to improve the course would be to add some small quizzes, maybe for participation grade only, to sort of get ahold of how the tests will be before we take them. Besides that, keep up the amazing work you’re doing, Dr Dunbar!

- Doc Dunbar is one awesome guy! He really is passionate about this subject and it comes across in his teaching methods. I appreciate the time he spent making sure the class understood that all religions have value. He is doing a great job in this course.

- This course has taught me how to analyze films. The course might be improved if it had a longer meeting time.

- The instructor explains the material very well.

- Dr. Dunbar is a huge fan of cinema. He loves lecturing about the movies after we watch them and always has to make himself stop and chuckle to give the students a chance to discuss the movies as well. He encourages independent thinking and comments and doesn’t force any view points on you, letting you interpret the movie as you see fit. The vocab was a difficult task to learn because we received a huge list at the beginning of the semester but only covered maybe 10 of them on the first day and had to learn the rest on our own for the mid term and final.

- This wasn’t like any other class I’ve ever taken in my life. I had a lot of “ah ha!” moments. It was the best and I’m very upset it’s over. The course is best at night when there is only 16-20 ish students. That’s when we really connect and learn.

- I love movies in general, but this class helped me find and understand the concept.

- This course was tough but you have to be passionate and open to learning and it makes it easier. Lots of vocabulary but you will get the definitions as you go and Dr. Dunbar will answer any questions on them.

- I learned about different religions and cultures and religious movements.

- He explained the material very well and was always open to questions.

- Dr. Dunbar is a great Professor. He is really passionate about all religions and can basically answer any question on the subject. The in class discussions on each chapter really help your understanding.

- This course dramatically changed my film and cinema experience. I will be using everything I have learned from this class this semester and using it in my life. It changed my perspective.

- This course has given me a new outlook on films, and the powerful messages behind them.

- I learned about different religions and cultures and religious movements.

- I have learned a lot about cinema.

- The instructor is very passionate about what he teaches. I love that he comes to class every day ready to talk about a film. Very informational class.

- He spends time explaining everything for the students.

- The course was educational and fun. He help me to see things in movies that, prior to his class, never crossed my mind. I will be looking at movies from a totally different perspective from now on. You cannot improve on perfection!

- I thoroughly enjoyed the class. I believe i learned a great amount of information after taking the class. I believe the course could improve by perhaps adding more time for discussion.

- I have always enjoyed Dr. Dunbar’s teaching and this class was no exception. He explains the information so well and you understand that he is very passionate towards teaching it.

- Dr. Dunbar more than covered all the material we needed to know. Dr. Dunbar also very frequently tried to engage the class, but often the students would not adequately respond; I see this as a failing on the part of the students, Dr. Dunbar is more than friendly and is very easy to talk to; if any given student could not provide an opinion on a topic, he or she was not paying enough attention. In my opinion this course requires no improvement; however, additional opportunities for grades might make students more comfortable with the curriculum. His method of teaching was very informative.

- His selection of movies to watch might force me to change my selection of movies I choose to see as well. I cannot think of anything that needs to be changed.

See Appendix C for more comments from NWFSC students.

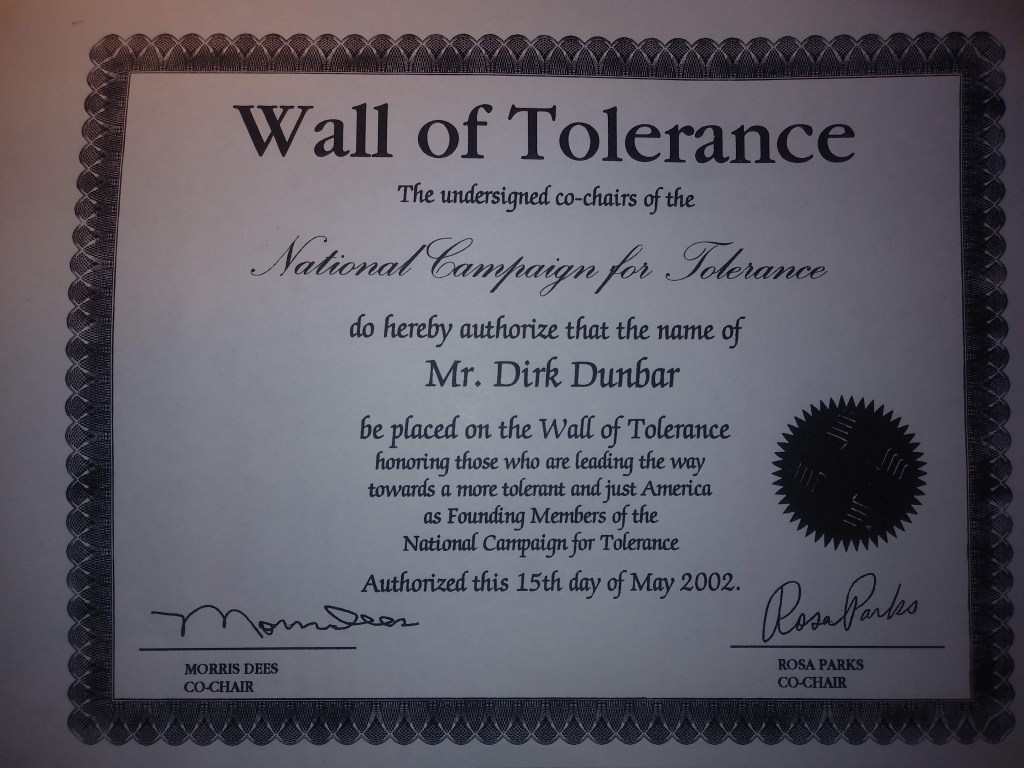

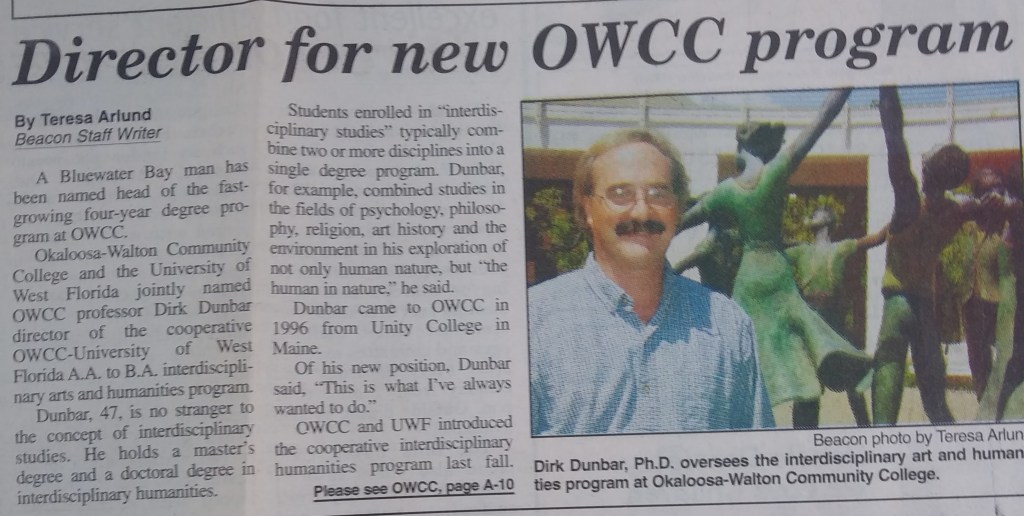

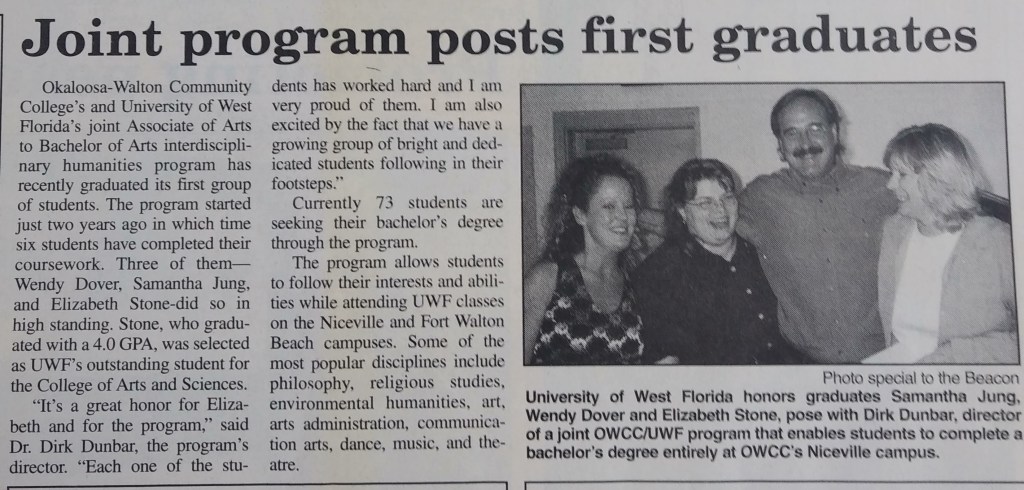

In the fall of 2000, the University of West Florida and OWCC received a grant to initiate an AA to BA Interdisciplinary Humanities program. Having an abundance of experience in learning, teaching, and administrating humanities, I was selected to serve as the director. It was a fantastic job and the source of some of my most meaningful work. For me, it was an easy sell. I was in charge of recruiting, advising, and organizing teachers for our courses at various campuses (including ones in Defuniak Springs, Niceville, Ft. Walton Beach, and Pensacola), was a liaison for each of those campuses, supervised two co-workers and graduate assistants, offered my own classes, assisted in marketing, arranged and/or participated in countless meetings, and coordinated disciplines between OWC and UWF. As you can tell from that list of courses I taught (some of which I created and others that I pulled from the UWF class catalog), I was having the time of my life in the classroom.

Alternative Philosophies; Environmental Humanities; Daoism and Ecology; Environmental Philosophy; Meeting of East and West in Contemporary Culture; Psychology of Religion; Philosophy of Religion; Philosophies of the East: Issues in Science and Religion; Alternative Philosophies; Philosophy of Art; Science, Religion, and Nature.

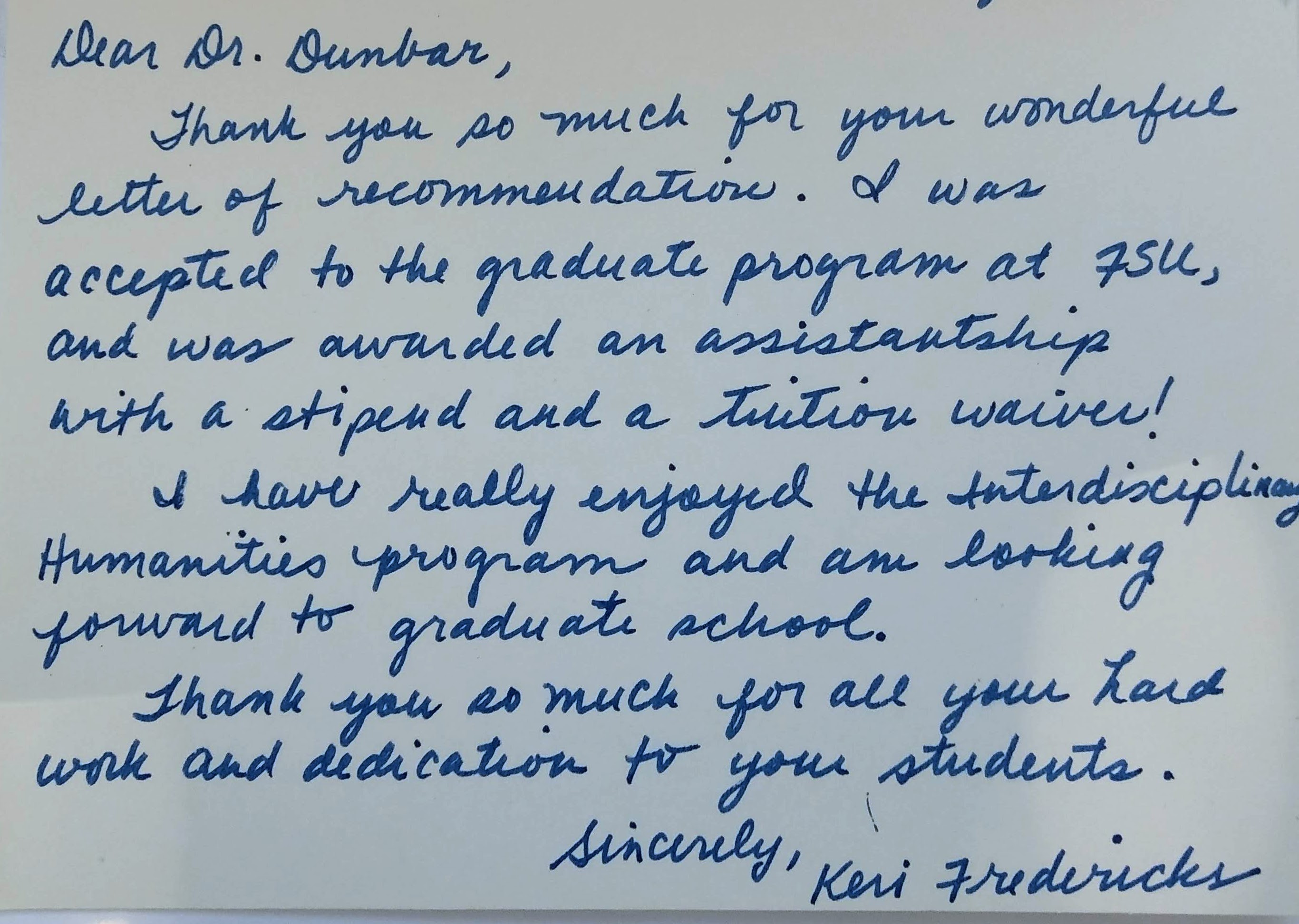

The program was a success for both institutions, the faculty involved as well as the students involved. I enjoyed building a close-knit relationship with all of the faculty, some of whom taught multiple classes each semester. Two stalwarts of the program, Ben Gillham, who taught digital multi-media, and Terry Prewitt, who taught anthropology and cultural ecology, exemplify the diversity of instruction and degree opportunities. To this day, I believe the program could serve as a model for higher education, especially for alternative students with multi-faceted interests who seek a meaningful life through learning as opposed to simply finding a career. After four years we had over 250 graduates, many of whom went on to graduate schools, became teachers (over 20 from grade school to university levels), or found other professions from environmental law, journalism, art curation, technical illustration, environmental research, and counseling to sales and management, library science, and dance instruction. The list goes on. I wrote over 200 letters of recommendation for graduates and still receive emails and cards of thanks. We had over 300 students in the program when it was cut (for conflicting political and short-sighted administrative reasons) in 2009. It was the most disappointing event during my tenure at OWC/NWFSC. Nonetheless, I am grateful that I had the opportunity to marry my passion in the classroom with my administrative abilities in ways that meant a great deal to students and colleagues alike.

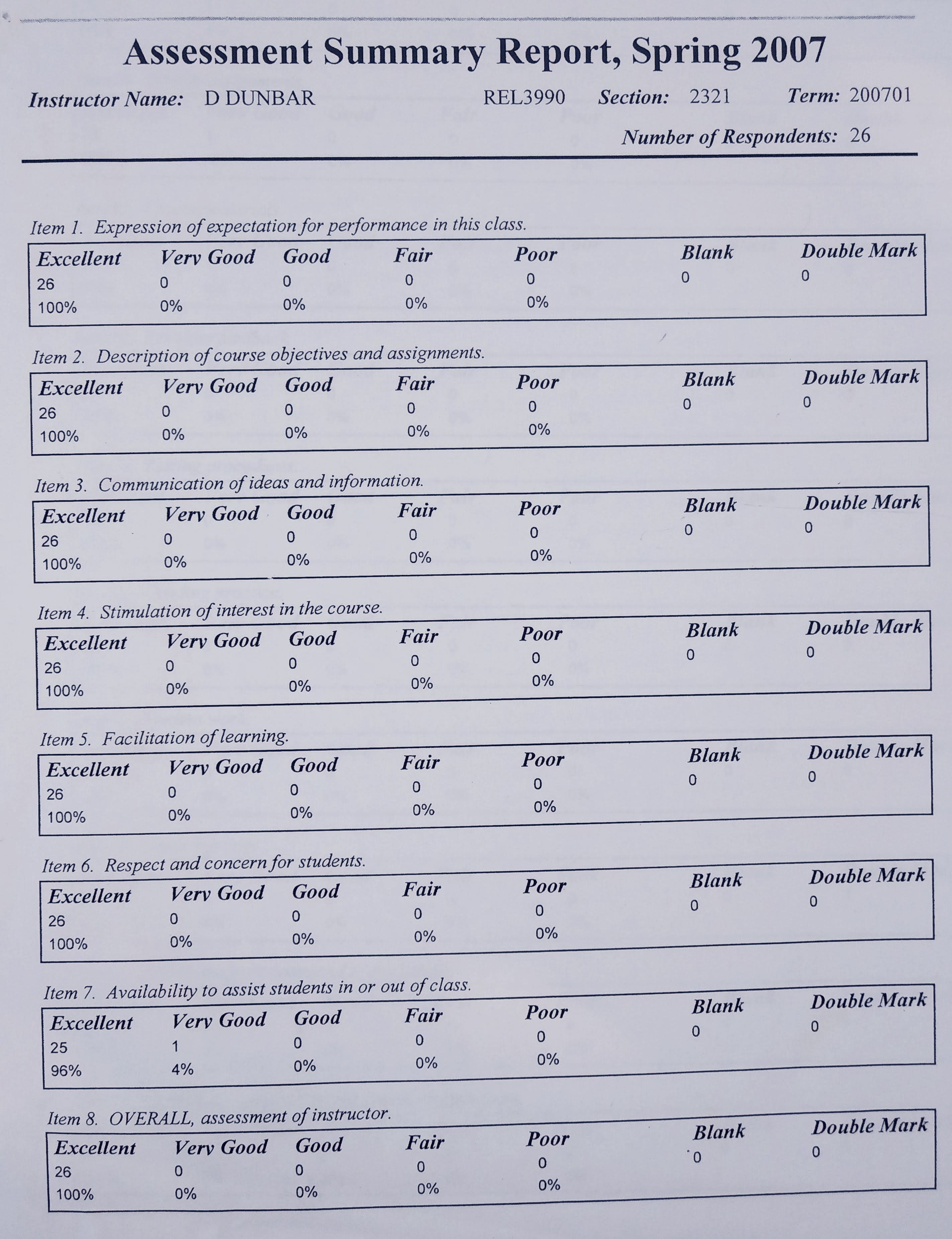

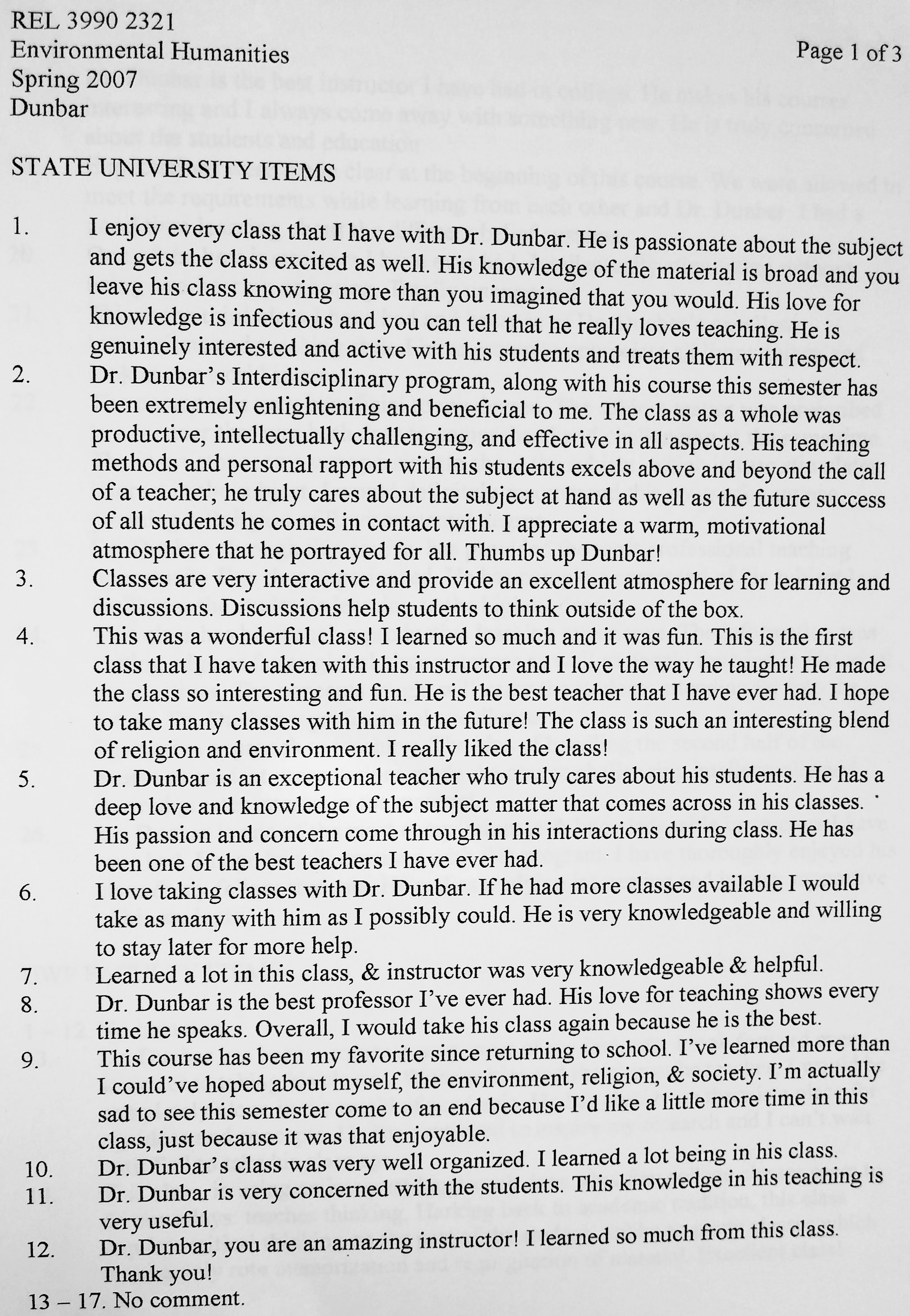

I won three UWF Outstanding Instructor awards and a Teaching Award from the National Institute for Staff and Organizational Development. I received some of my most remarkable student evaluations while teaching for and administrating the program, including multiple courses where all the students gave me 100% ratings and offered extremely positive comments—as the following comments indicate:

My Philosophy of Education

“If we want to reach real peace in this world, we should start educating children.”

A teacher who establishes rapport with the taught, becomes one with them, learns more from them than he teaches them.

I have always felt that the true textbook for the pupil is his teacher.

Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever. — Gandhi

The search for truth is the essence of learning and teaching. In a day and age when “the truth” is so often adulterated, ignored, or even scorned, who we are learning from and who we are teaching contributes to the health, balance, and viability–or lack thereof–of our families, communities, countries, and global relations. Truth cannot be defined but is also obvious; is not a matter of degrees, and, yet, is relative. You cannot pinpoint truth but it is there to be grasped. To hide the truth and hide from the truth is dangerous and irresponsible. It is necessary to keep as many avenues open to finding and expressing it as possible. Books should not be banned, critical race theory should be taught, and the perspectives of the LGBTQ community should be shared and honored. No one is above the truth. As Krishnamurti explains, “While offering information and technical training, education should above all encourage an integrated outlook on life; it should help the student to recognize and break down in himself all social distinctions and prejudices, and discourage the acquisitive pursuit of power and domination. It should encourage the right kind of self-observation and the experiencing of life as a whole, which is not to give significance to the part, to the ‘me’ and the ‘mine’, but to help the mind to go above and beyond itself to discover the real.”

I taught over 30 different courses, over 340 sections, and well over 6,000 students in my 33 years as a professor and my aim has always been to get students to discuss passionately and tolerantly issues that concern what it means to be humane, how values develop relative to social and environmental conditions, and how cross-cultural exchange could help heal dysfunctional relationships between sexes, races, nations, and humans and nature. For nearly every one of those years, I had to create portfolios (which served as the sources for most of the content of this whole page) and submit a “goals statement” or philosophy-of-teaching statement. My last one went something like this: “My goals as a teacher are to challenge and inspire students to engage their skills, find their interests and write intelligently about them, participate in class discussions, assist them in understanding course materials, and, most importantly, help them cultivate a passion for learning.” I consider teaching a privilege and an immense responsibility. A teacher can have a lifelong impact on students, which is why I always attempt to create an environment that promotes tolerance, open-mindedness, comradery, and reciprocal communication and understanding.

The following is a message I received September, 2024 from a former who student earned her Anthropology degree in Alaska:

Hey! How’s it going, Doc?

I thought one day we would make it back to Florida and I would come visit to say this in person. It seems, however, that we are a bit delayed in that, and a million miles from where we were or planned to be. And it’s not terrible! I do think it’s important to give credit where credit is due, though.

Out of every professor along the way, you were my inspiration to keep going, even years down the line, as life moved on and away from that space in time. I knew you believed in me, whether I had way too much going on or got too excited to participate! I hadn’t felt that way about myself, let alone the idea that anyone else believed in me. So much has changed in my life, but most significantly, this soul has been altered. Tattooed, as it were. Connecting with you and Hailey in class on such a level had a profound impact on not only who I was then, but has informed all interactions moving forward. This was the first time in life I’d been able to really scratch at the surface of belief and identity with anyone, to uncover meanings that can only be derived from the combination of individual contemplation and community collaboration.

I saw your movements between the life of an athlete to that of a philosopher as a clear indicator that growth comes in many forms and can often have many surprises for us along the way. While you were always much more than an athlete or professor, as we all have many facets, these were two different versions of you, two different lives, on one journey. Today it has become something much more like one soul stopping to find pieces of itself along a path, and that soul is you, me, all of us. Every once in awhile, one of your lessons falls on me like a warm breeze, reminding me of the layered existences we all find ourselves in. And it’s beautiful.

Learning from a professor who was able to be so completely “chill” while remaining so engaged in the subject matter and student interactions was the first indicator that growth was afoot. I’d never had great experiences with school, even in the few college courses before this one. Though there were several that were “okay,” none of the professors really had the same spark, especially with group conversation! So, I know I should have spent more time talking with you while at NWFSC, and definitely should have done a better job of conveying this to you sooner and staying connected since. Although, who I am today sees that these earlier versions of me were not able to comprehend or articulate much of what was happening, and couldn’t fathom what changes were to come.

I’ve discovered parts of myself since then that, while they may have always lay dormant, wouldn’t have emerged when and how they did had I not walked into your class that semester.

I don’t know much about your life, or your family, but I appreciate that these people and experiences helped forge a professor capable of teaching his students to know and trust themselves and to be excited about knowledge. I believe educators like you are one of our most important assets, and you should know, even if only for yourself, the positive impacts you have had on so many lives. So thank you for being such a rad dude, Doc.

Peace, Amber

It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy in creative expression and knowledge. — Albert Einstein

Teaching might even be the greatest of the arts since the medium is the human mind and spirit. -– John Steinbeck

Inclusive, good-quality education is a foundation for dynamic and equitable societies.– Bishop Tutu

Unfortunately, the education afforded children is like the health care available to the poor: both testify that our institutionalized drive to “get ahead” has created a value system that is more concerned with what we own than who we are. The major precepts of our educational system are exposed in governmental tests, such as Terra Nova and Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test, which aim at quantifying and categorizing our children’s analytic abilities. Terra Nova tests the three R’s while the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test covers reading, science, and mathematics. As part of the growing implementation of performance-based education, such tests attempt to stress analytic abilities that help categorize and program children. The goal is measured in, for instance, the Florida “voucher system,” which determines what schools receive money and praise, and which are reprimanded and lose their best students, who are free to choose even private schools at taxpayers’ expense. This system, which has been called “a death knell for public education,” was expanded by Florida’s governor last year. While teachers must submit to the “new accountability era” of improving student scores on standardized tests, many or most students are left with an educational system that preaches conformity and denies them the opportunity to develop their individual, particularly intuitive, capabilities. Art and humanities programs are being drastically cut while areas involving, for instance, the STEM coalition (an acronym for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) receive the bulk of educational funds. We are failing to educate the whole person and, instead, are promoting technical efficiency void of heart and soul. As Krishnamurti explains:

“There is an efficiency inspired by love which goes far beyond and is much greater than the efficiency of ambition; and without love, which brings an integrated understanding of life, efficiency breeds ruthlessness. Is this not what is actually taking place all over the world? Our present education is geared to industrialization and war, its principal aim being to develop efficiency; and we are caught in this machine of ruthless competition and mutual destruction. If education leads to war, if it teaches us to destroy or be destroyed, has it not utterly failed?”

O this learning, what a thing it is!

A fool thinks himself to be wise, but a wise man knows himself to be a fool.

Learning is never done without errors and defeat.

— William Shakespeare

Despite the foci in schools, children in the United States continue to lag behind other first-world countries in math and science because of the way we go about teaching them. I recognize the significance of developing analytic skills, but am afraid that we have been, and still are, killing the innate joy of learning with an educational system based on competition and grades that promotes standardization and specialization. In many ways, we tend to separate education from life. For instance, our culture makes it easy to ignore or lose touch with simple ways of doing things that help sustain health—like breathing. We are taught the importance of creating proper sentence structure and breaking down math problems, while abilities cultivated through meditation remain foreign, and, consequently, we seem unaware that the length, depth, and focus of our breathing relate directly to our state of mind. I think our failure to overlook so much that is vital to our lives, from eating habits to our environmental impact, is due in part to body-denying spirituality and the significance we have placed on “getting ahead” in schools and the job market. Learning is a joy in itself and to assume compulsion encourages learning is a false premise of our entire educational system. As Einstein proclaims:

“It is, in fact, nothing short of a miracle that the modern methods of instruction have not yet entirely strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry; for this delicate little plant, aside from stimulation, stands mainly in need of freedom; without this it goes to wrack and ruin without fail. It is a grave mistake to think that the enjoyment of seeing and searching can be promoted by means of coercion and a sense of duty.”

In sum, I believe by teaching tolerance and respect for diversity, we encourage students to see unique perspectives are healthy and inspire discourse, that enemies are often created through prejudice and misunderstanding, and that all people are products of their genetic heritage and the physical environment in which they are raised. People merit respect regardless of race, creed, or conviction. Only through dialogue can opposing perspectives entertain consideration, reconsideration, and potential understanding. The terms conservative and liberal, for instance, refer respectively to people who hold to established institutions and values, and to people who seek change while questioning traditional norms, methods, and values associated with orthodoxy. Traditions make us who we are and should be respected, but change encourages growth and makes new traditions possible. People from conservative and liberal camps, alike, realize that we all carry the capacity for love and hate and that stereotyping one another encourages animosity and misunderstanding. True change can only occur when we see that, despite the differences, we belong to one community. As Helen Keller states, “The highest result of education is tolerance.”

Here is my Curriculum Vita:

https://dirkdunbar.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/dirk-dunbar-vitae.docx

The heart must work together with the brain to manifest the vibrational conditions necessary to co-create the life of your desires.

Trust the heart; it has its own intelligence.

If you can create a coherent vibration between your DNA, mind, and heart, you will have access to unimaginable power.– Mike Murphy

From: Ashley Lundy

Sent: Thursday, August 9, 2018 12:08 PM

To: Dirk Dunbar <dunbardi@nwfsc.edu>

Hi Dr. Dunbar!

I’m sure you don’t remember me with all the students you have taught over the years. I took your philosophy class in 1999 when the college was still OWCC. I wrote a paper about Acupuncture and you told me my understanding was deeper than the norm and that I should pursue this further (I found the paper yesterday in my attic!). You encouraged me to look into schooling and read and learn as much as my brain could withstand! I wanted to let you know I followed your advice and am happier than I ever dreamed possible with my career!! I’ve been a Doctor of Oriental Medicine for 13 years, interned in China and have a successful private practice in the suburbs of Birmingham. On a daily basis people ask me how I ended up in this field and I tell the story of your encouragement. In case there is ever a day that you wonder if you make a difference, I wanted you to know that you shaped the being I am and I am so grateful!!! I hope you are well and continuing to open minds and possibilities for people that feel limited in their upbringing and communities!!

With deepest respect and sincerity,

Ashley Lundy (formerly Johns)

Appendix A

Here are further FSU student comments from my first years as an instructor:

The following comments are from a film class during my last semester at FSU when the department started typing the evaluations:

Appendix B

Unity student comments:

Appendix D

More comments from UWF students: